ANIMUSANIMAL

The Word That Named Every Creature That Breathes

Breath. Soul. The invisible force that separates

the living from the dead.

“breath, soul, life force”

The invisible force that separates the living from the dead

The Breath of Life

Greek & Roman World • 350 BCE – 100 CE

The classical world where philosophy first named the living

The story begins not with beasts, but with breath. In the ancient Mediterranean, the word that would become "animal" started as something invisible—the vapor that entered a body at birth and departed at death.

to breathe

The reconstructed root that gave rise to Latin anima, Greek anemos (wind), and Sanskrit ātman (soul)

From this ancient root, the Romans derived anima—the breath of life, the soul made manifest in respiration. And from anima, they created animalis: "having breath" or "having a soul."

breath, soul, life force, the vital principle

Aristotle

The Father of Zoology

384–322 BCE

- First systematic classification of living things

- Wrote De Anima (On the Soul) and Historia Animalium

- Defined animals by sensation and voluntary movement

- Greek ζῷον (zōion) translated to Latin animalis

"The soul is the cause and principle of the living body."

— De Anima, Book II

Aristotle divided nature into three categories: things that grow (plants), things that feel (animals), and things that reason (humans). The animal was defined by sensation—the ability to perceive and respond to the world.

Before we named them by their forms, we named them by their breath. The taxonomy was theological before it was biological.

"Each creature a letter in God's alphabet"

Beasts in Parchment

Christian Europe • 500 – 1500 CE

Medieval manuscript—where animals became moral lessons

In medieval Europe, the Latin animal underwent a profound transformation. Christianity collapsed Aristotle's three categories into two: humans (with immortal souls) and animals (with merely mortal breath).

Isidore of Seville

The Last Scholar of the Ancient World

c. 560–636 CE

- Wrote Etymologiae—the medieval encyclopedia

- Provided canonical etymology: 'animalia' from 'anima'

- Bridge between Roman knowledge and medieval understanding

"Animals are so called because they are animated by life and moved by spirit."

— Etymologiae, Book XII

The bestiaries flourished—gorgeously illustrated manuscripts cataloging real and mythical animals. But these were not natural history texts. Each creature was a letter in God's alphabet, spelling out divine truth.

The lion represented Christ. The pelican symbolized sacrifice. The unicorn embodied purity. Animals existed not as biological specimens but as moral lessons.

The lion—king of beasts, symbol of Christ in medieval bestiaries

a living being other than a human; a beast

From Old French animal, from Latin animalis

The medieval animal was half biology, half theology—a breathing sermon in fur and feather.

The Cabinet of Curiosities

The Cabinet of Nature

Age of Observation • 1450 – 1700

Cabinets of curiosities—where wonder replaced worship

The Renaissance brought rediscovery: ancient texts, new lands, new species. European explorers returned with armadillos, hummingbirds, opossums—creatures that fit no medieval category.

The question changed. Medieval scholars asked: what does this animal mean? Renaissance naturalists asked: what is this animal? How does it move, eat, reproduce?

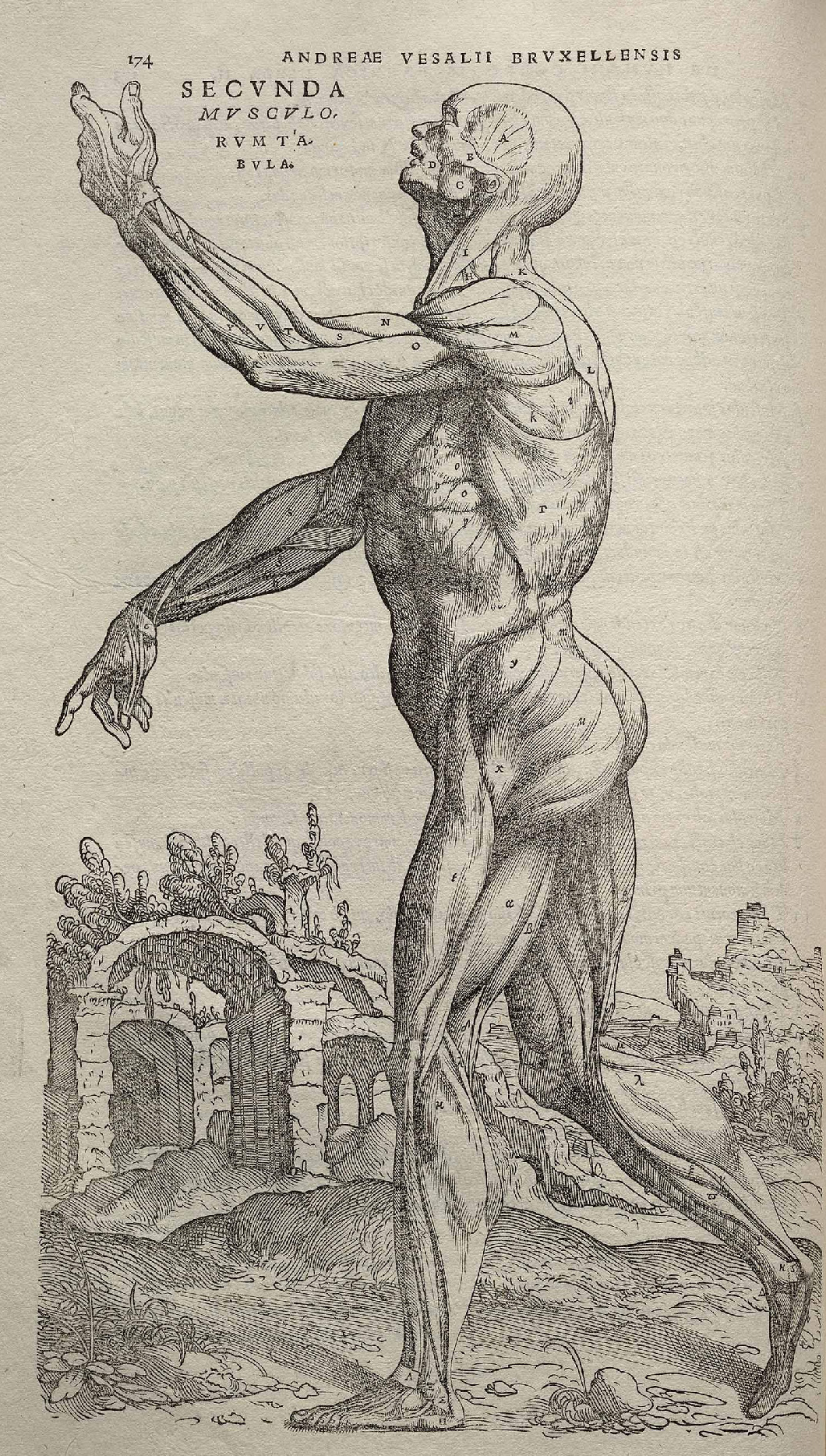

Comparative anatomy revealed hidden connections across species

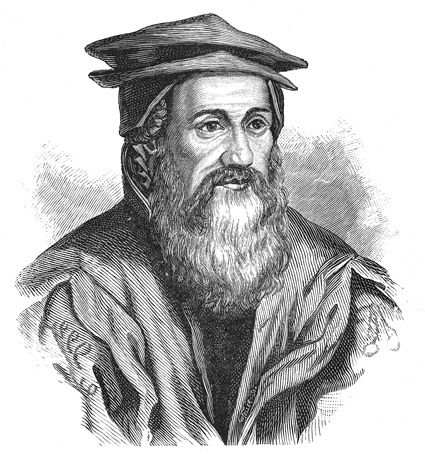

Conrad Gessner

The Father of Modern Zoology

1516–1565

- Historia Animalium (1551-1558): first modern zoological encyclopedia

- Attempted to catalog every known animal

- Combined ancient sources with firsthand observation

- Published over 4,500 pages on animal life

Wonder replaced worship. The animal became a puzzle to solve, not a sermon to interpret.

Naming the Kingdom

The Age of Classification • 1735 – 1859

Systema Naturae—the book that named every living thing

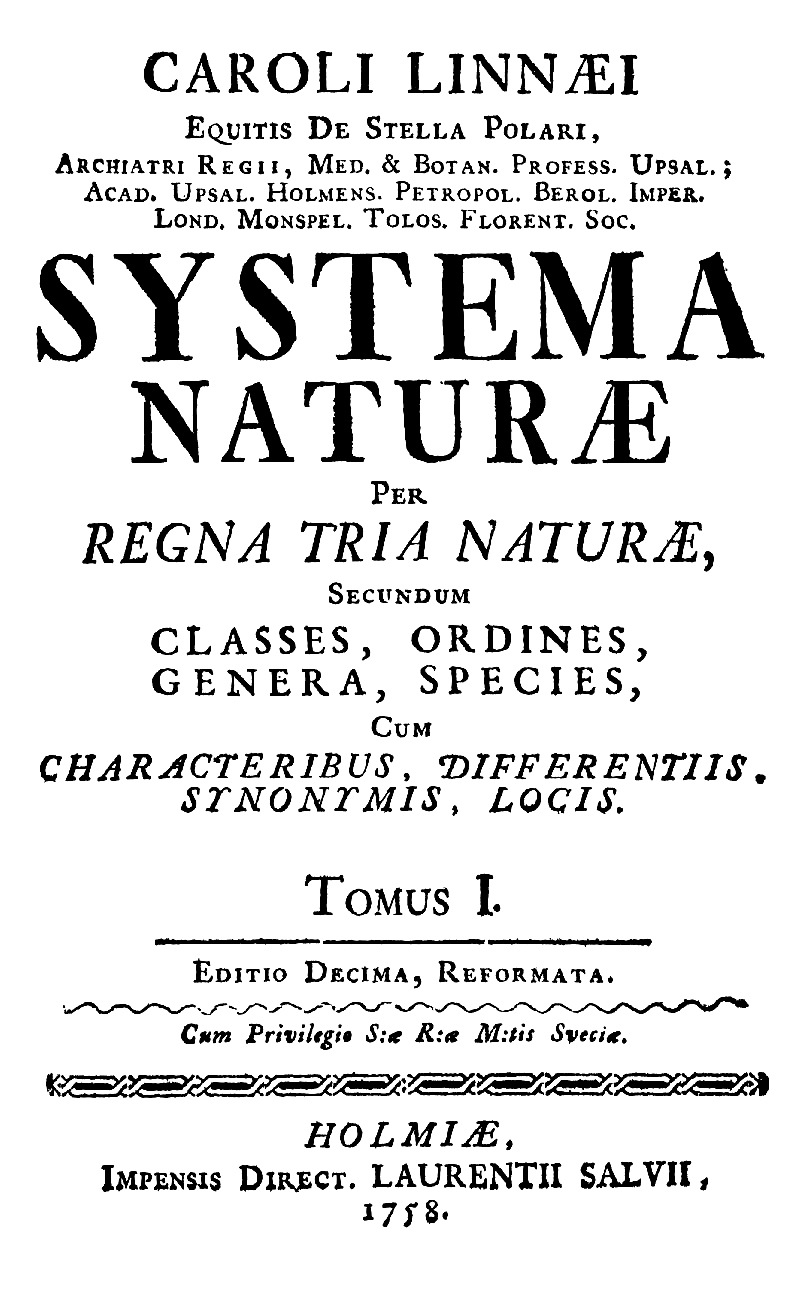

Carl Linnaeus changed everything. In 1735, the Swedish botanist published Systema Naturae, a slim catalog that would grow through twelve editions into the foundation of modern taxonomy.

Linnaeus formalized what had been chaos. He divided nature into three kingdoms: Animalia, Vegetabilia, and Mineralia. For the first time, "animal" had a precise scientific boundary.

The taxonomic kingdom comprising all animals

Linnaeus's 10th edition of Systema Naturae established binomial nomenclature

Carl Linnaeus

The Father of Taxonomy

1707–1778

- Created binomial nomenclature (Genus species)

- Established Kingdom Animalia in Systema Naturae

- Placed humans within Animalia as Homo sapiens

- Made 'animal' a precise scientific term

"I demand of you, and of the whole world, that you show me a generic character by which to distinguish between Man and Ape."

— Systema Naturae, 10th edition

Natura non facit saltus. Nature does not make leaps.

— Carl Linnaeus, 1758

This was revolutionary—and controversial. Linnaeus had used the ancient Latin animalis not to separate humans from beasts, but to unite them. We were Homo sapiens—the "wise man"—but animals nonetheless.

Science reclaimed the word. The hierarchy of souls collapsed into the democracy of species.

The Family Tree

Evolution's Dawn • 1859 – 1900

The tree of life—Darwin's radical insight that all life is connected

If Linnaeus arranged life into a system, Darwin explained how it got that way. On the Origin of Species (1859) proposed that all animals shared common ancestry—that the kingdom Animalia was not a divine filing system but a family tree.

Charles Darwin

The Father of Evolution

1809–1882

- Proposed evolution by natural selection

- United all animals through common ancestry

- Made 'animal' a genealogical term, not just categorical

- The Descent of Man (1871): humans explicitly descended

"We thus learn that man is descended from a hairy quadruped, furnished with a tail and pointed ears, probably arboreal in its habits."

— The Descent of Man, 1871

The fossil record—ancestors frozen in stone

The word "animal" suddenly meant something deeper: not just "having breath," but "descended from breath-havers." Every animal was cousin to every other, separated only by millions of years and millions of mutations.

Endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

— Charles Darwin, 1859

We are animals not by category but by ancestry. The word became a family name.

From breath to biology, from soul to sequence

Cousins in the Mirror

The Molecular Age • 1900 – Present

DNA sequencing reveals the molecular definition of 'animal'

Modern biology has both complicated and clarified the meaning of "animal." DNA sequencing allows us to trace ancestry with precision impossible for Linnaeus or Darwin. The kingdom Animalia is now defined by molecular characteristics.

Any member of the kingdom Animalia; a multicellular eukaryotic organism developing from a blastula

Current scientific and colloquial usage

~99% of our DNA is shared with chimpanzees—cousins in the mirror

Jane Goodall

The Chimpanzee's Champion

1934–present

- Revolutionized understanding of animal intelligence and emotion

- Recognized individual chimpanzees as persons with names

- Challenged the strict human/animal divide through observation

- Advocated for animal rights and conservation

"In what terms should we think of these beings, nonhuman yet possessing so very many human-like characteristics?"

— Through a Window, 1990

The numbers are staggering. Animalia includes approximately 1.5 million described species—and perhaps 8.7 million total, most yet to be cataloged. From tardigrades measuring 0.1mm to blue whales at 30 meters. All sharing that ancient quality: they breathe, in some form.

From breath to biology, from soul to sequence—the word evolved with our understanding, and carries every layer still.

The Breath Remains

You are witnessing anima made flesh.

The breath that named a kingdom.