“”

— Alan Turing, 1950

He asked the question in 1950. He never lived to see the answer.

THE THINKING MACHINE

A Visual History of Artificial Intelligence

1943 — 2025The Eternal Question

Talos

The bronze giant of Greek mythology, built by Hephaestus to guard Crete. Humanity's first dream of an artificial protector.

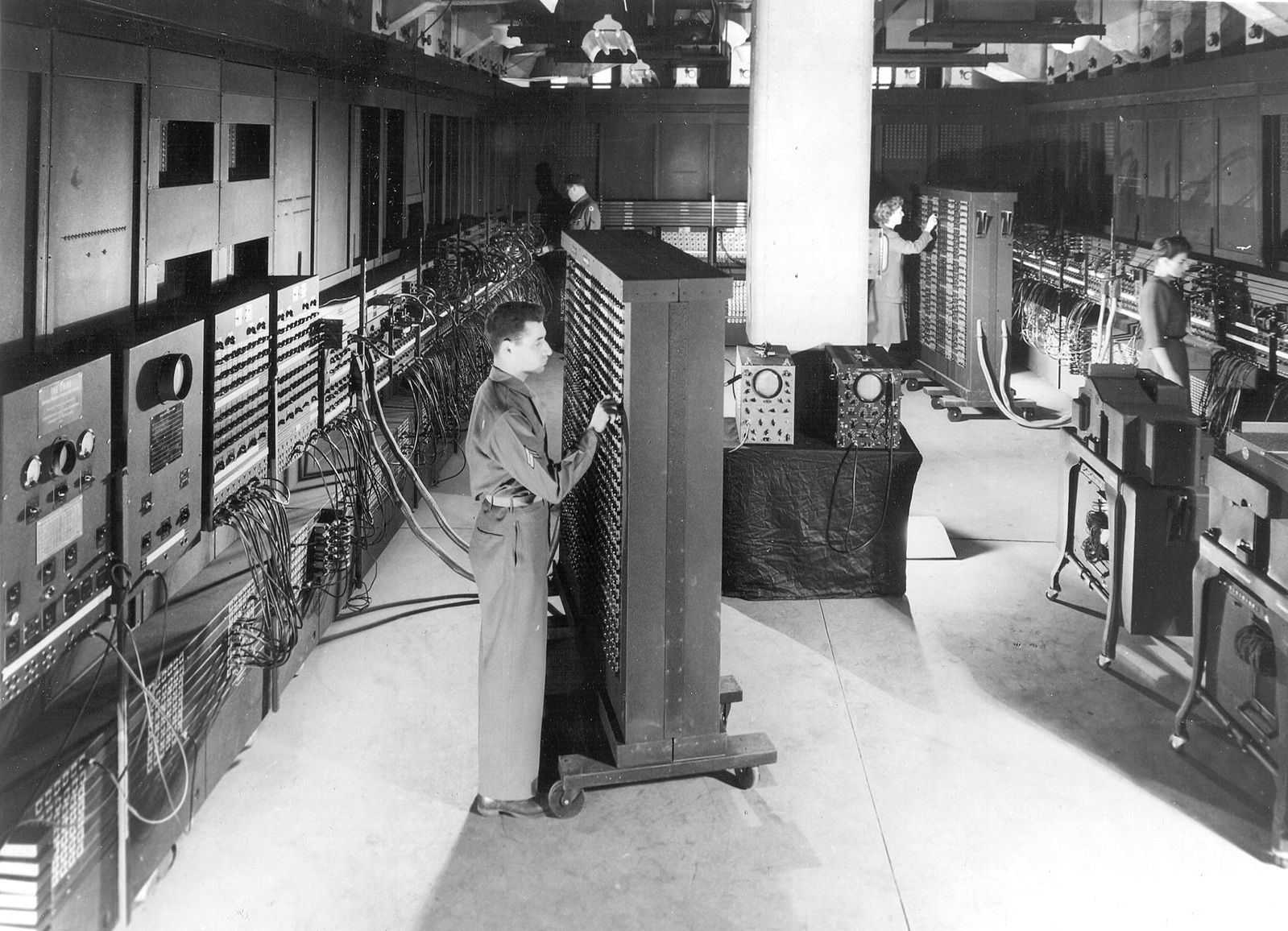

In 1946, ENIAC filled a room and consumed 150 kilowatts of power to perform calculations a modern smartphone does in microseconds. But to the engineers who built it, the question was already forming: If a machine can calculate, can it think?

The Prophet

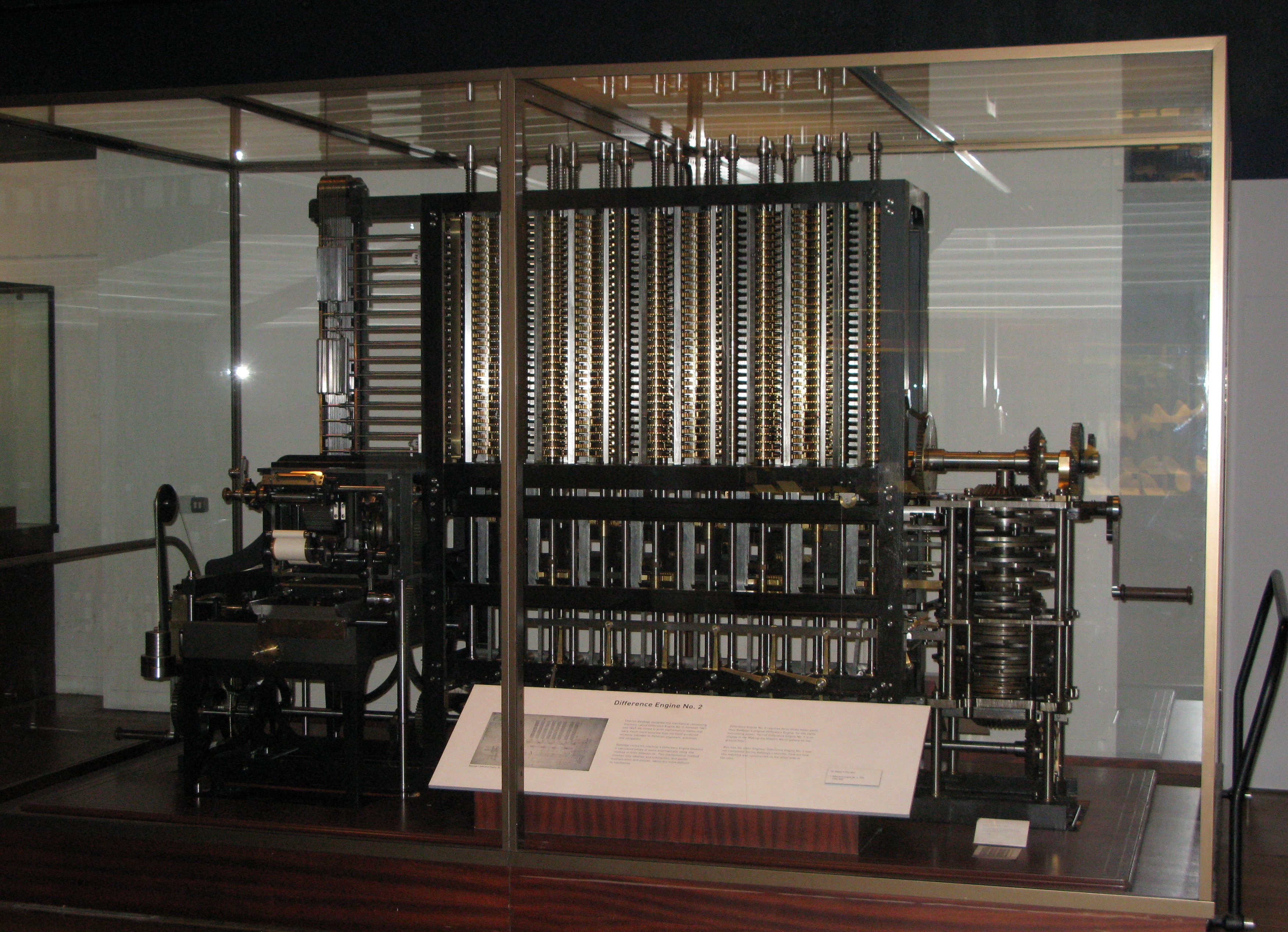

Before there were computers, Alan Turing imagined them. His 1936 paper on computable numbers described a theoretical machine that could perform any calculation—the mathematical foundation for every computer that followed.

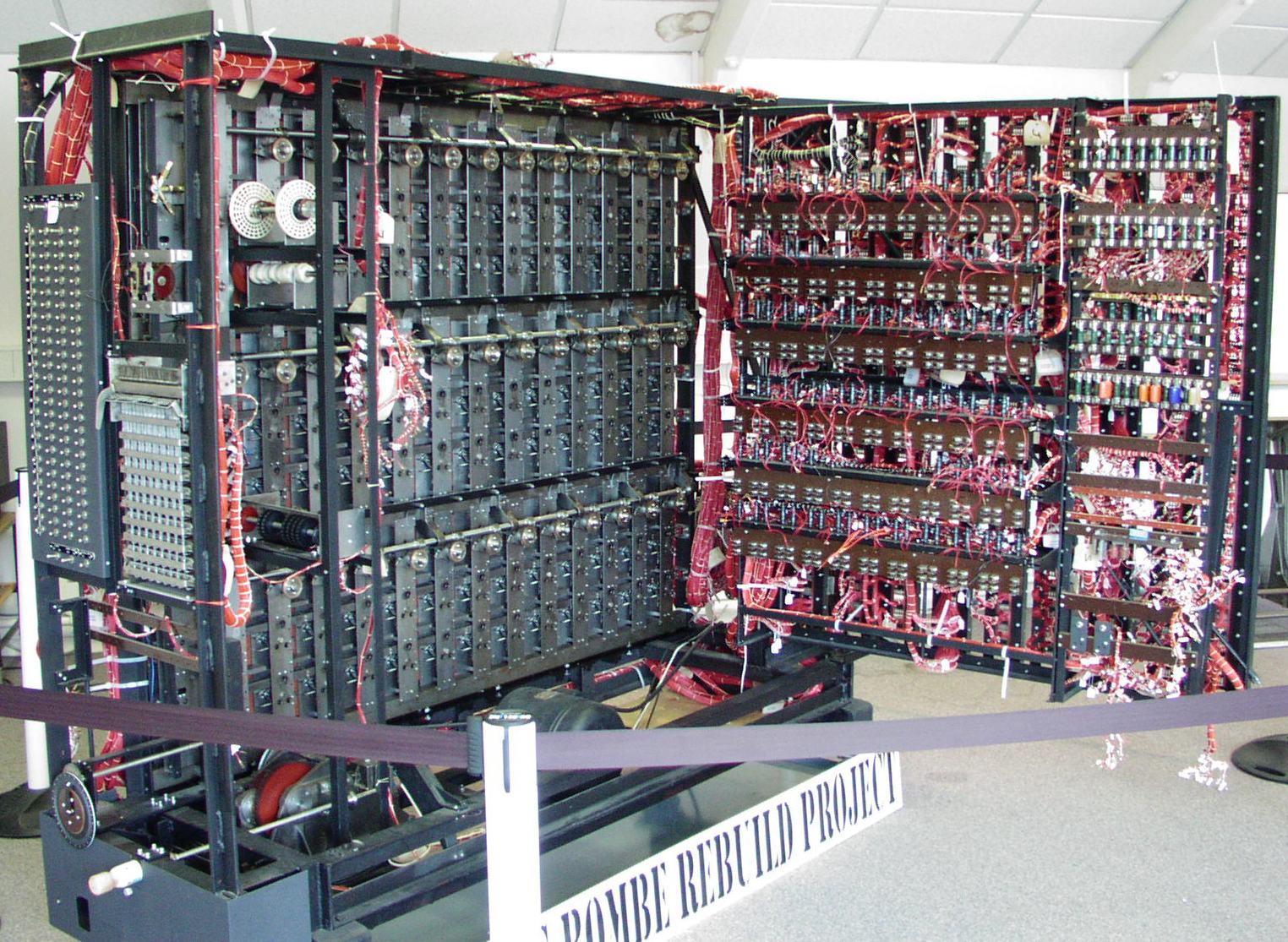

During World War II, he built machines that broke Nazi codes and shortened the war by an estimated two years, saving countless lives.

“We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done.”

— Alan Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” 1950

In 1950, he asked the question that launched artificial intelligence: “Can machines think?”

The Tragedy

Turing never saw the field he founded. Prosecuted for homosexuality in 1952, chemically castrated by the British government, he died in 1954 at forty-one. An apple laced with cyanide. The father of computer science, destroyed by the society he helped save.

- Invented the theoretical computer (1936)

- Broke the Enigma code (1939-1945)

- Proposed the Turing Test (1950)

- Died by suicide after government persecution (1954)

- Pardoned by the British government in 2013—59 years too late

The Dartmouth Summer

They believed they could solve it in 2 months.

It would take 70 years.

They were brilliant. They were wrong about the timeline.

But they were right that it could be done.

That summer, they gave the field its name: artificial intelligence.

The workshop didn't solve AI. But it created a community, a vocabulary, and a dream that would survive decades of disappointment.

The Golden Age

The early years delivered wonders. Programs that proved mathematical theorems. Machines that recognized patterns. Robots that navigated rooms.

A chatbot named ELIZA convinced users it understood them—even though its creator knew it was just clever pattern matching. Its creator, Joseph Weizenbaum, was disturbed when his secretary asked him to leave the room so she could have a private conversation with the program.

Funding flowed. DARPA believed. The researchers made promises: machine translation in five years, human-level AI in a generation.

Frank Rosenblatt — The Neural Network Pioneer

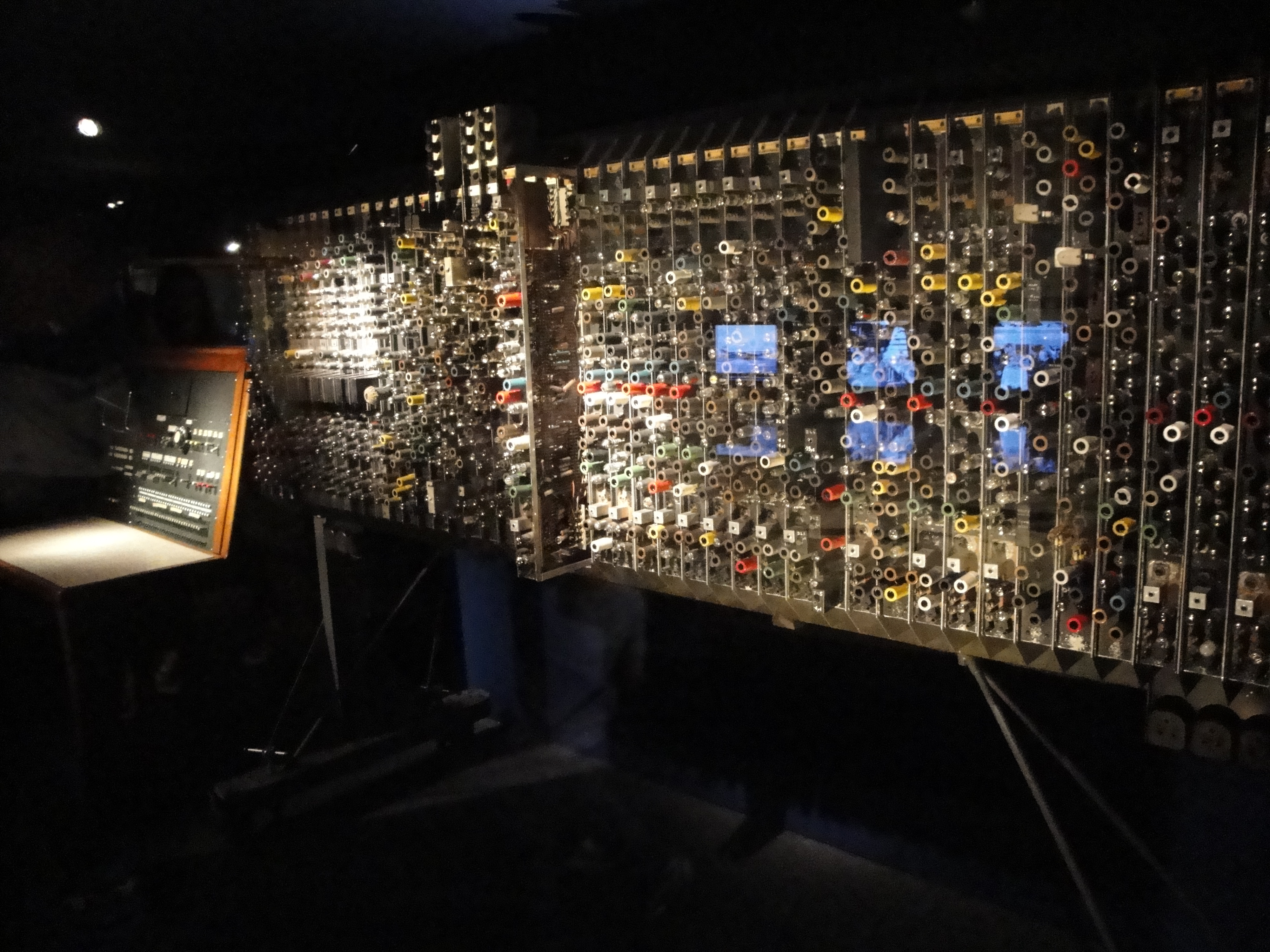

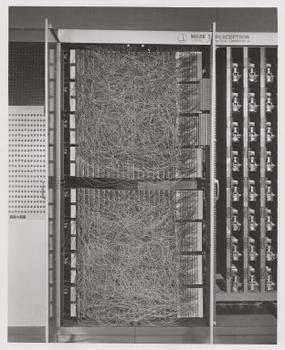

Vindicated sixty years laterIn 1958, Rosenblatt built the Perceptron—hardware that learned from examples. He predicted machines would “be conscious of their existence.” The New York Times ran the headline: “Navy Reveals Embryo of Computer Designed to Read and Grow Wiser.”

In 1969, Minsky and Papert published a book proving perceptrons couldn't solve important problems. Funding for neural networks collapsed. Rosenblatt died in a boating accident in 1971, his work dismissed. It took fifty years to prove he was right all along.

The First Winter

“In no part of the field have the discoveries made so far produced the major impact that was then promised.”

— Sir James Lighthill, 1973

The dream froze. Those who remained became cautious. The word “AI” itself became toxic. Researchers rebranded their work as “machine learning” or “expert systems”—anything but artificial intelligence.

The Expert Systems Boom

Commercial salvation arrived in the form of “expert systems”—programs encoding human expertise as rules.

Banks used them for loan decisions. Hospitals for diagnosis. The market boomed. Companies spent billions. Japan announced the Fifth Generation Computing project—a national effort to dominate AI. America panicked. Funding returned.

But expert systems were brittle. They couldn't learn. They couldn't handle ambiguity. They required armies of human experts to build and maintain.

The Second Winter

The expert systems bubble burst. Companies that had rebranded everything as “AI” collapsed. The backlash was brutal.

AI researchers learned to never use those two letters in funding proposals. The field retreated to the margins of computer science.

But in small pockets—Toronto, Montreal, a few European labs—a different approach survived. Neural networks. The approach that Minsky and Papert had “killed” in 1969.

A handful of researchers believed that if networks got big enough and had enough data, something different might emerge.

They couldn't prove it. They couldn't get funding. They persisted anyway.

The Believers

Geoffrey Hinton

The Godfather of Deep LearningToronto“I've always believed this would work. I just didn't know when.”

Yann LeCun

The Convolutional PioneerBell Labs → Facebook AI“Deep learning will transform the world.”

Yoshua Bengio

The Quiet ArchitectMontreal“We were outcasts. We believed anyway.”

ACM Turing Award

Hinton

Hinton LeCun

LeCun Bengio

Bengio“For conceptual and engineering breakthroughs that have made deep neural networks a critical component of computing”

Vindication forty years in the making.

They published papers no one read. They trained students who couldn't get jobs. They believed in an idea the world had abandoned.

And they were right.

The ImageNet Moment

ImageNet Top-5 Error Rate

The field went into shock. Within months, every major tech company was hiring neural network researchers.

Fei-Fei Li had spent years building ImageNet when funding agencies called it “unimportant.” Her dataset became the proving ground for a revolution.

Deep Learning Conquers

Deep learning didn't just succeed at vision. It consumed domain after domain. Speech recognition. Language translation. Game playing. Medical diagnosis. Autonomous vehicles.

In 2016, Google DeepMind's AlphaGo defeated Lee Sedol at Go—a game long thought to require human intuition beyond any algorithm.

“Move 37” — AlphaGo's move that shocked the Go world. Commentators called it creative. Beautiful.

— A machine had demonstrated creativity

The question shifted from “Can neural networks work?” to “What can't they do?”

Demis Hassabis — The Game Player

Former chess prodigy who founded DeepMind- Founded DeepMind with the explicit goal of building AGI

- AlphaGo, AlphaFold, Gemini

- “We're building the most transformative technology in human history”

The Transformer

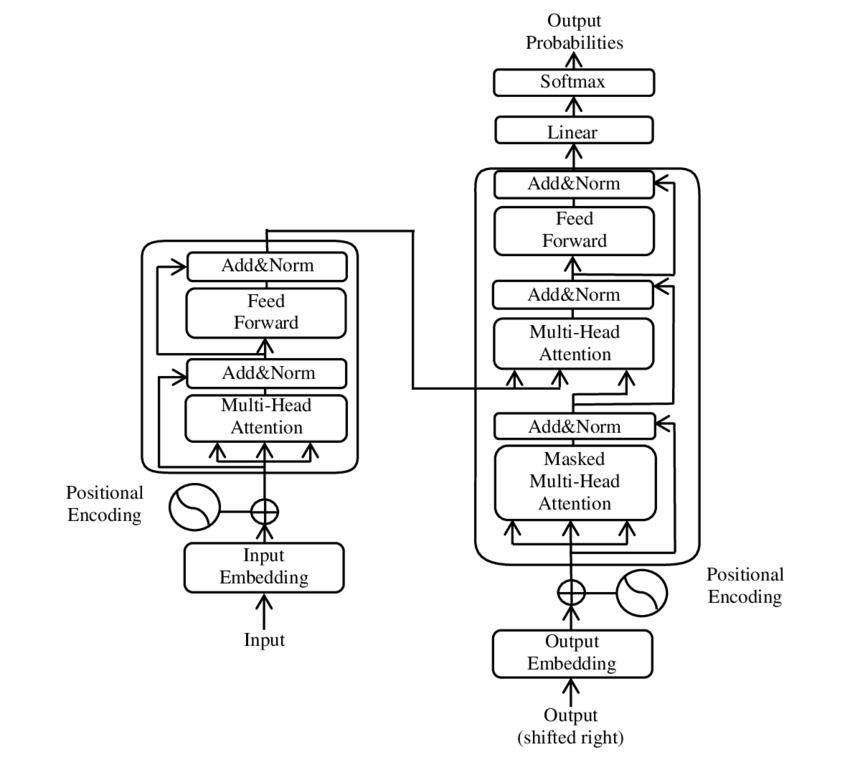

In 2017, a team at Google published an eight-page paper titled “Attention Is All You Need.”

The paper's impact was nuclear. Within two years, transformers dominated natural language processing. Then vision. Then audio. Then biology.

The transformer architecture became the universal foundation for modern AI. It introduced the “attention mechanism”—a way for models to focus on relevant context across entire sequences.

The authors didn't fully anticipate what they'd unleashed. Several later expressed concern about the acceleration they enabled.

Attention: The model learns which words relate to each other

Language Models Awaken

GPT-1

OpenAI releases GPT-1—a transformer trained on raw text. It could write coherent paragraphs. Interesting, but limited.

GPT-2

Good enough to frighten its creators. They delayed release, worried about misuse. The first AI “too dangerous to release.”

GPT-3

Could write essays, code, poetry. It felt like something had shifted. 175 billion parameters. Researchers began to wonder if scale was all you needed.

ChatGPT

The fastest-growing consumer application in history. 100 million users in two months. For the first time, ordinary people could converse with AI that felt genuinely capable.

The technology that researchers had pursued for seventy years was suddenly in everyone's pocket.

Sam Altman

The AccelerationistCEO of OpenAI“We're on the cusp of the most transformative technology humanity has ever created.”

Dario Amodei

The Safety-Conscious BuilderCEO of Anthropic“We're in a race—we'd rather the safety-focused labs be at the frontier.”

Daniela Amodei

The Institutional ArchitectPresident of Anthropic“Building the organizational guardrails for AI safety.”

Ilya Sutskever

The Young VisionaryCo-founder of OpenAI“It may be that today's large neural networks are slightly conscious.”

The Reckoning

The field that spent decades begging for attention now faces something unexpected: fear.

Not the science-fiction fear of robot uprisings, but concrete concerns about misinformation, job displacement, concentration of power, and systems too complex for their creators to understand.

“I've come to believe that these things could become more intelligent than us... and we need to worry about how to stop them from taking over.”

— Geoffrey Hinton, 2023 (after leaving Google)

The researchers who built modern AI are themselves uncertain about what they've created. The debates that once seemed philosophical—consciousness, alignment, control—are now engineering challenges without clear solutions.

The story of AI has reached the present tense. Its ending is unwritten.

The Open Question

In 1950, Alan Turing asked:

“Can a machine think?”

Now new questions layer over it:

“Should a machine think?”

“Who controls a thinking machine?”

“What happens when machines think better than we do?”

In 2025, machines are asking humans to define what thinking means.

The answer will shape everything that follows.

The user who completes this essay now understands not just what AI is, but why it took so long, why it suddenly accelerated, and why the people who built it are themselves uncertain about what comes next.

Sources & Further Reading

Key Works & Books

- Nils J. Nilsson, "The Quest for Artificial Intelligence" (2009)

- Pedro Domingos, "The Master Algorithm" (2015)

- Cade Metz, "Genius Makers" (2021)

- Stuart Russell & Peter Norvig, "Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach"

- Michael Wooldridge, "The Road to Conscious Machines" (2020)

Archives & Primary Sources

- Computer History Museum — AI Gallery

- MIT Museum — Artificial Intelligence Collection

- Stanford AI Lab Historical Archives

- ACM Digital Library

- IEEE Annals of the History of Computing

Original Papers

- Alan Turing, "Computing Machinery and Intelligence" (1950)

- McCarthy et al., "A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project" (1955)

- Rosenblatt, "The Perceptron" (1958)

- Rumelhart, Hinton, Williams, "Learning representations by back-propagating errors" (1986)

- Vaswani et al., "Attention Is All You Need" (2017)

Contemporary Sources

- OpenAI Research Publications

- Google AI Blog

- DeepMind Publications

- Anthropic Research

- arXiv Machine Learning Archive

Photography Credits

Historical photographs sourced from public archives including the Computer History Museum, MIT Museum, Stanford AI Lab Archives, and various university collections. Contemporary photographs from press releases and news photography, used under fair use for educational purposes. Era-specific visual treatments (grayscale, sepia, color grading) applied to evoke historical periods.