Rwanda

The Land of a Thousand Hills

Ntarama Church

April 1994

The doors were open.

Darkness inside.

Silence where there should be life.

On April 15, 1994, over 5,000 people were murdered at Ntarama Church.

They had come seeking sanctuary.

The killers followed them inside.

This church is now a memorial.

These bones are real.

The scale of industrial genocide achieved with machetes.

KWIBUKA

A Hundred Days of Darkness, A Generation of Light

Kwibuka — “To remember”

Before the Storm

Rwanda Before Colonial Contact

Landscape of Rwanda showing terraced hills

Before the Europeans arrived, Rwanda was one of Africa's most centralized and sophisticated kingdoms. The Mwami (king) ruled through a complex hierarchy of chiefs and sub-chiefs. The society was organized not primarily by ethnicity but by clan, region, and occupation.

The terms Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa did exist—but they were fluid categories, more like social classes than fixed ethnicities. Hutu generally referred to cultivators, Tutsi to cattle-keepers, and Twa to forest-dwelling potters and hunters. Intermarriage was common. A wealthy Hutu who acquired cattle could become Tutsi through a process calledkwihutura. The categories were permeable.

Understanding this pre-colonial complexity is essential. The genocide of 1994 was not the eruption of “ancient tribal hatreds.” Those hatreds were manufactured—and the manufacturers were European.

Kigeli IV Rwabugiri

The Last Great Mwami

- Ruled Rwanda 1853-1895, the most powerful king in Rwandan history

- Expanded the kingdom through military conquest

- Centralized administration and strengthened royal power

- Died just before German colonizers arrived

“Rwanda was a nation before Europe named it one.”

The Colonial Poison

Manufacturing Ethnicity

Germany colonized Rwanda in 1897, but it was Belgium—granted the territory after World War I—that would engineer the ethnic division that enabled genocide.

The Belgians arrived with the Hamitic Hypothesis: a pseudoscientific theory that “superior” African peoples must have descended from Ham, Noah's son, and migrated from the north. The taller, thinner Tutsi, they decided, were these Hamitic invaders—natural rulers, almost European. The shorter, broader Hutu were the “native” Bantu—born to serve.

In 1933, Belgium introduced identity cards requiring every Rwandan to be classified as Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa. This card would become, sixty years later, the instrument of selection at roadblocks across Rwanda.

“I simply described what I saw”

— Richard Kandt, German colonial administratorBut description became prescription—and prescription became death sentence.

The First Blood

Independence, Revolution, and Exile

As independence approached, Belgium reversed course. Having ruled through the Tutsi minority, they now backed the Hutu majority in a calculated transition of power. The “Hutu Revolution” of 1959-1961 inverted the colonial hierarchy through violence.

Hutu Revolution Begins

Tutsi homes burned. Thousands killed. First wave of refugees flees to Uganda, Burundi, Congo.

Independence

Grégoire Kayibanda leads independent Rwanda with explicit Hutu supremacist ideology.

Periodic Pogroms

Waves of violence punctuate the decades. After each, more refugees flee. By 1990: 750,000 in exile.

Habyarimana Seizes Power

General Juvénal Habyarimana rules for twenty-one years, building the apparatus of genocide.

Fred Rwigyema

The General Who Almost Came Home

- Co-founder of the Rwandan Patriotic Front

- Hero of the Ugandan civil war, decorated general

- Led the RPF invasion of October 1990

- Killed on the second day of the invasion

His death forced his friend Paul Kagame to take command.

The Death of Peace

The Arusha Accords and Their Enemies

International pressure forced negotiations. The Arusha Accords of August 1993 promised power-sharing, integration of the RPF into a new government, and the return of refugees. Peace seemed possible.

But the akazu had no intention of sharing power. As diplomats celebrated, the extremists prepared genocide.

“The graves are not yet full. Who will help us fill them?”

“Cut down the tall trees.”

“The enemy is the Tutsi.”

RTLM (Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines) broadcast ethnic hatred daily. The Tutsi were called inyenzi (cockroaches) and inzoka (snakes).

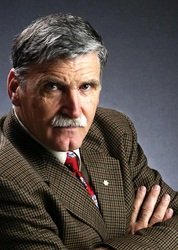

Roméo Dallaire

The General Who Was Ordered Not to Save

- Canadian general commanding UN forces in Rwanda (UNAMIR)

- Warned headquarters of impending genocide, was ordered to stand down

- Watched helplessly as murder unfolded

- Wrote Shake Hands with the Devil, essential memoir

“We watched as the devil took control of paradise on earth.”

Suffered severe PTSD; attempted suicide. Dedicated life to genocide prevention.

⚠️ This chapter documents mass murder. Images are selected to convey scale while maintaining victims' dignity.

One Hundred Days

The Genocide

Ntarama Church Memorial - where over 5,000 people were murdered seeking sanctuary

On April 6, 1994, at 8:20 PM, a plane carrying President Habyarimana was shot down over Kigali. Within an hour, the killing began.

The genocide was not spontaneous chaos. It was organized, planned, and directed. The Presidential Guard and army established roadblocks. The Interahamwe fanned out with machetes and lists of names. The radio instructed: “The graves are not yet full.”

A road in Rwanda. April 1994.

“Carte d'identité.”

Show your papers.

This happened over one million times in 100 days.

Scroll to continue

Churches became killing grounds. At Nyarubuye, 35,000 were murdered in the church compound. At Ntarama, over 5,000. At Murambi Technical School, 45,000. The sanctuaries became abattoirs.

“In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart.”

— Anne Frank (1929-1945)Anne Frank's words resonate with Rwanda's survivors—many of whom found the strength to forgive.

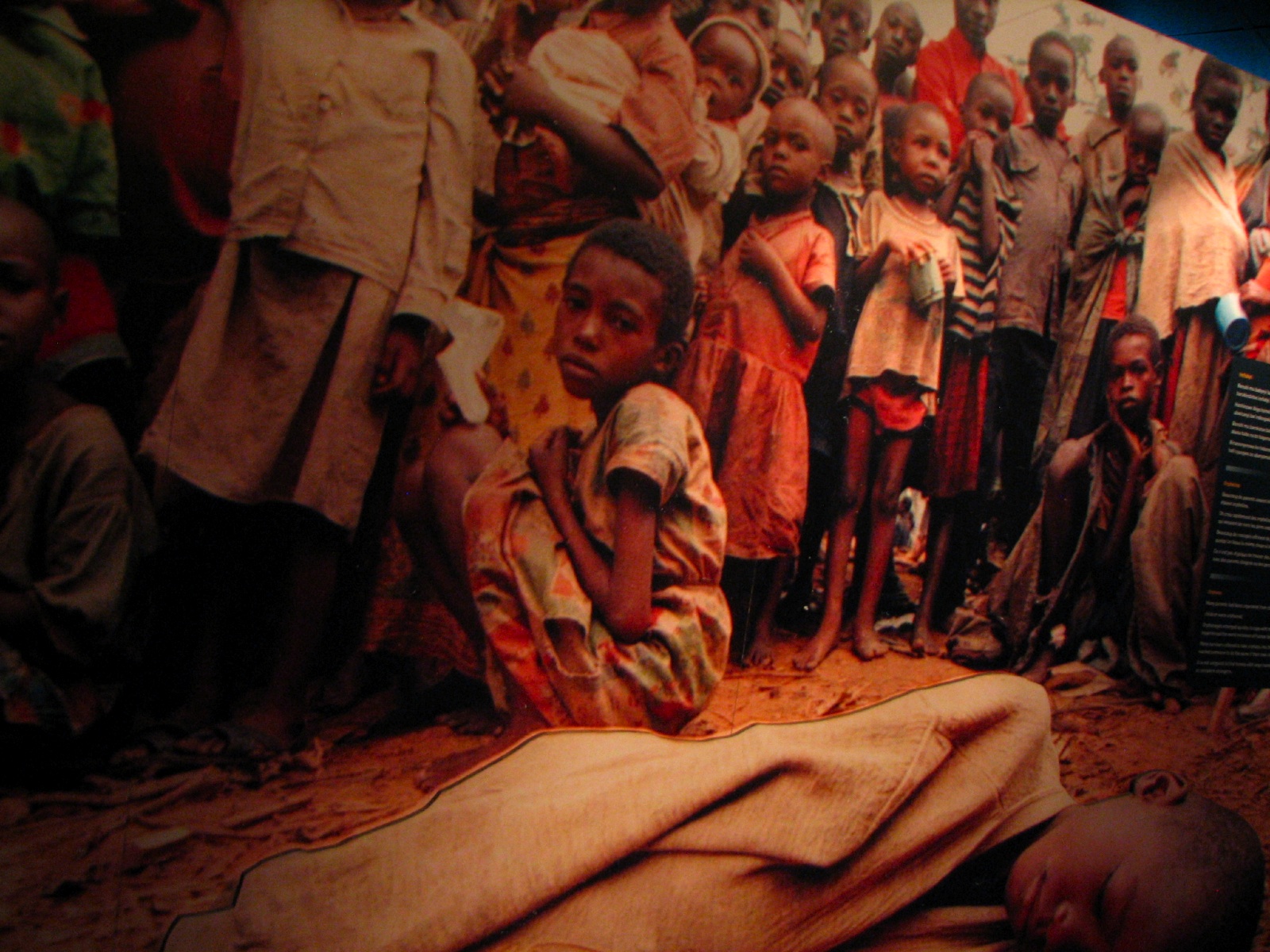

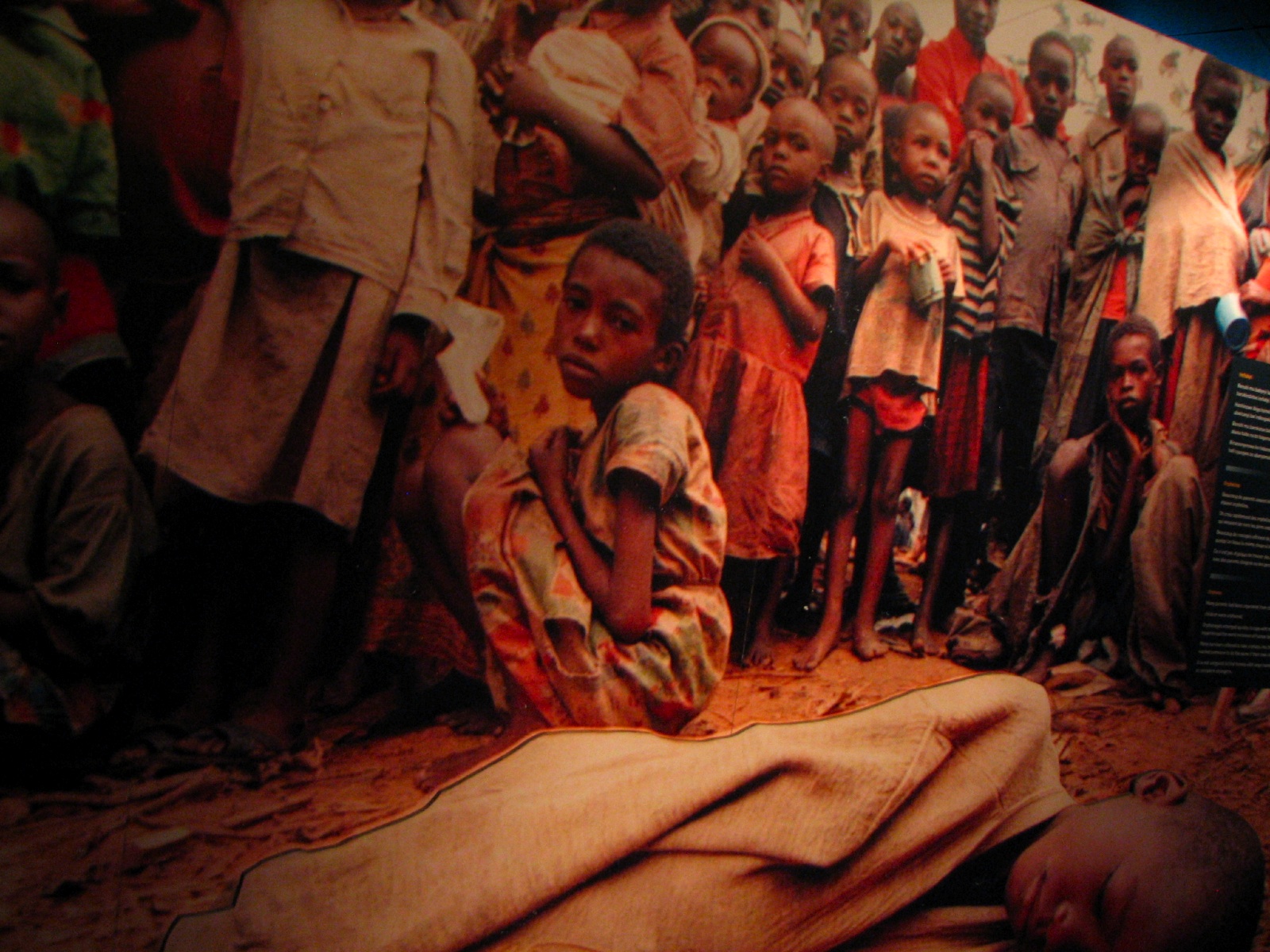

Child survivors of the Tutsi genocide

Immaculée Ilibagiza

The Woman Who Prayed in the Bathroom

- Survived 91 days hiding in a 3×4 foot bathroom with seven other women

- Sheltered by a Hutu pastor who risked his life

- Emerged to find her entire family murdered except one brother

- Wrote Left to Tell, met her family's killer, forgave him

“Forgiveness is all I have to give.”

The World Looked Away

International Failure

The genocide succeeded because the world let it happen.

General Dallaire commanded 2,500 UN peacekeepers in Rwanda. On January 11, 1994, he sent his now-famous “genocide fax” to UN headquarters, detailing Interahamwe training, weapons caches, and plans for extermination. He requested permission to raid the weapons.The request was denied.

UN Security Council • April 21, 1994

“We must be careful with language...”

“Acts of genocide may have occurred...”

The United States, scarred by Somalia, refused to use the word “genocide” because international law would require action. Belgium withdrew its forces after ten soldiers were murdered. Rather than reinforce, the Security Council voted toreduce UNAMIR to 270 troops.

“We did not act quickly enough after the killing began. We should not have allowed the refugee camps to become safe havens for the killers. We did not immediately call these crimes by their rightful name: genocide.”

— President Bill Clinton, 1998Four years too late.

Kofi Annan

The Future Secretary-General Who Failed to Act

- Head of UN Peacekeeping during the genocide

- Received and did not act on Dallaire's genocide fax

- Later became Secretary-General, acknowledged the failure

“In Rwanda, we made unforgivable mistakes.”

Rwanda was the shame that haunted his career.

President Clinton meeting genocide survivors in Kigali, 1998 - four years after the genocide

Liberation

The RPF Victory

The genocide ended not because the world intervened, but because the RPF won the war.

On July 4, 1994, RPF forces captured Kigali. Over the following two weeks, they swept across the country. On July 18, the RPF declared the war over.

What they found defied comprehension. Churches filled with bones. Entire villages empty. Bodies in rivers, in fields, along roads. The smell of death everywhere.

The Pivotal Choice

The RPF—a predominantly Tutsi force that had lost family members in the genocide—faced the question that would define Rwanda's future: revenge or reconstruction?

They chose reconstruction. There was no counter-genocide. The new government declared that there would be no Hutu, no Tutsi—only Rwandans.

Paul Kagame

The Commander Who Became President

- Born 1957, fled to Uganda as a child

- Rose through Ugandan military, co-founded RPF

- Took command after Rwigyema's death

- Led the RPF to victory and ended the genocide

- President of Rwanda since 2000

“Rwanda's history will not be written by outsiders.”

Controversial but transformative leader—architect of Rwanda's reconstruction.

Exodus and Aftermath

The Refugee Crisis

Kibumba refugee camp at Goma, Zaire - where millions fled in 1994

As the RPF advanced, two million people fled westward into Zaire. They were a mixture: genuine refugees fleeing war, and génocidaires fleeing justice.

Among them: the perpetrators. The Interahamwe evacuated intact, bringing their weapons—and their ideology. The camps became states-within-states, armed and hostile.

The international community, having failed to stop the genocide, now rushed to help the refugees. But the camps were controlled by the génocidaires. Aid meant to feed refugees instead sustained the killers.

The Poison Spreads

The génocidaires used the camps as bases for cross-border raids into Rwanda. In 1996, Rwanda invaded Zaire, scattered the camps, and helped install Laurent-Désiré Kabila. The First Congo War had begun—a conflict that would kill millions and destabilize the region for decades.

The genocide did not end in July 1994. Its consequences are still being felt.

Justice and Reconciliation

Gacaca and the Choice to Rebuild

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) - where genocide architects faced justice

Rwanda Makes Peace - the path of reconciliation

After the genocide, Rwanda faced an impossible problem: over 100,000 genocide suspects in prisons built for 10,000. A traditional court system would have taken over a century to process them all.

They chose another way.

The Gacaca Courts

Rwanda revived and adapted the traditional Gacaca system—community justice courts where local judges heard cases, perpetrators could confess, and survivors could confront those who had harmed them.

“I cannot forgive. But I can live next to you.”

— A survivor, speaking to her family's killer at GacacaThe impossible conversation, repeated thousands of times across Rwanda.

The Gacaca system was imperfect. Some perpetrators lied. Some survivors could not bear to participate. But it accomplished something remarkable: the conversation happened. Perpetrators faced their victims. Many confessed. Some survivors forgave—not because they forgot, but because they chose to live alongside those who had wronged them.

Théoneste Bagosora

The Colonel Convicted as Genocide's Architect

- Senior military officer, considered the operational planner of the genocide

- Convicted by ICTR of genocide, crimes against humanity

- Sentenced to life imprisonment

The 'mastermind' who organized the infrastructure of death—brought to justice.

Land of a Thousand Hills Rising

Rwanda's Transformation

Modern Kigali - from ashes to one of Africa's cleanest and safest cities

From the ashes of genocide, Rwanda has achieved what many considered impossible.

The Transformation

From 1994 baseline to present day

The government abolished ethnic identity cards. It is illegal in Rwanda to identify as Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa—there are only Rwandans. The monthly umuganda (community service day) brings all citizens together for public works.

Kigali is one of Africa's cleanest and safest cities. Corruption is among the lowest in Africa. Rwanda has the highest percentage of women in parliament of any country in the world.

The Debate Continues

This transformation is not without critics. Kagame has extended his rule through constitutional changes and faces accusations of authoritarianism, suppression of dissent, and involvement in neighboring conflicts. Opposition politicians have been imprisoned. Journalists who criticize the government face consequences.

The question of Rwanda's future is genuine: Is this a development model for Africa, or a benevolent dictatorship? What happens after Kagame?

But one thing is undeniable: a nation that experienced genocide did not collapse. It rebuilt. It functions. Its people, in their millions, go about the ordinary business of life—which is perhaps the greatest revenge against those who tried to end life entirely.

Agnes Binagwaho

The Doctor Who Rebuilt Healthcare

- Pediatrician, former Minister of Health

- Architect of Rwanda's universal healthcare system

- Reduced child mortality by 70%

“Health is not a luxury. It is the foundation of everything.”

Kwibuka

“To remember”

Every April, Rwanda stops. The nation remembers. The dead are named. The survivors speak. The world is invited to witness.

Remembrance is not passive. It is an act of resistance against forgetting. Against denial. Against the forces that made genocide possible.

One million people were murdered because the world had categories for them. Because propaganda made them less than human. Because neighbors became killers. Because those who could have intervened chose not to.

But Rwanda did not end. It rose. Not perfectly. Not without controversy. But it rose.

The living and the dead share the land of a thousand hills.

And the living have chosen to remember.

Twibuke. Twiyubake.

Remember. Rebuild.

Sources & Further Reading

- Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda — Human Rights WatchInstitution

- The Rwanda Genocide — United States Holocaust Memorial MuseumInstitution

- Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda — Roméo DallaireDocumentary

- We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families — Philip GourevitchJournalism

- Machete Season: The Killers in Rwanda Speak — Jean HatzfeldJournalism

- The Order of Genocide: Race, Power, and War in Rwanda — Scott StrausAcademic

- A History of Modern Rwanda — Christian Scherrer (Cambridge University Press)Academic

- Kigali Genocide Memorial — Official WebsiteInstitution

- International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) — UN ArchivesArchive

- Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust — Immaculée IlibagizaDocumentary

- Rwanda: The Preventable Genocide — OAU International Panel of Eminent PersonalitiesInstitution

- Conspiracy to Murder: The Rwandan Genocide — Linda MelvernJournalism

This narrative was fact-checked against peer-reviewed scholarship, institutional reports, and authoritative historical records. The 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi is extensively documented by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, Human Rights Watch, and the Kigali Genocide Memorial.