The Medieval Toye

Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343–1400) — The Father of English Poetry

Anonymous, c. 15th century. National Portrait Gallery, London. Public Domain.

The word “toy” first appears in English around 1303, and it has nothing to do with children. In the medieval imagination, a toye was a dalliance—a flirtation, a romantic interlude, perhaps something improper. To “toy with” someone was to engage in amorous play.

The Canterbury Tales — where 'toy' first appears meaning 'frivolous talk'

William Caxton, 1484. British Library. Public Domain.

Medieval courtly love — the context where 'toy' meant 'dalliance'

Codex Manesse, c. 1300-1340. University Library Heidelberg. Public Domain.

The etymology itself is mysterious. Scholars debate whether “toy” descends from Middle Dutch toi (ornament, finery), or emerges independently from English wordplay. What's certain is its early semantic field: frivolity, worthlessness, idle amusement.

For medieval writers, the word carried a whiff of moral suspicion. To spend time on “toys” was to waste it. The word was already teaching a lesson about value.

Geoffrey Chaucer

The Poet Who First Toyedc. 1343–1400- Among the earliest recorded users of 'toy' in Middle English

- Used the word to mean idle talk and trifling matters

- His Canterbury Tales established many words in English literature

“Nor did she deign to touch food with her fingers, but would command her eunuchs to cut it up into small pieces, which she would impale on a certain golden instrument with two prongs.”

— Peter Damian, on Byzantine customs, c. 1060

Trifle and Dalliance

William Shakespeare — used 'toy' 30+ times, never meaning 'plaything'

John Taylor (attributed), c. 1600-1610. National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain.

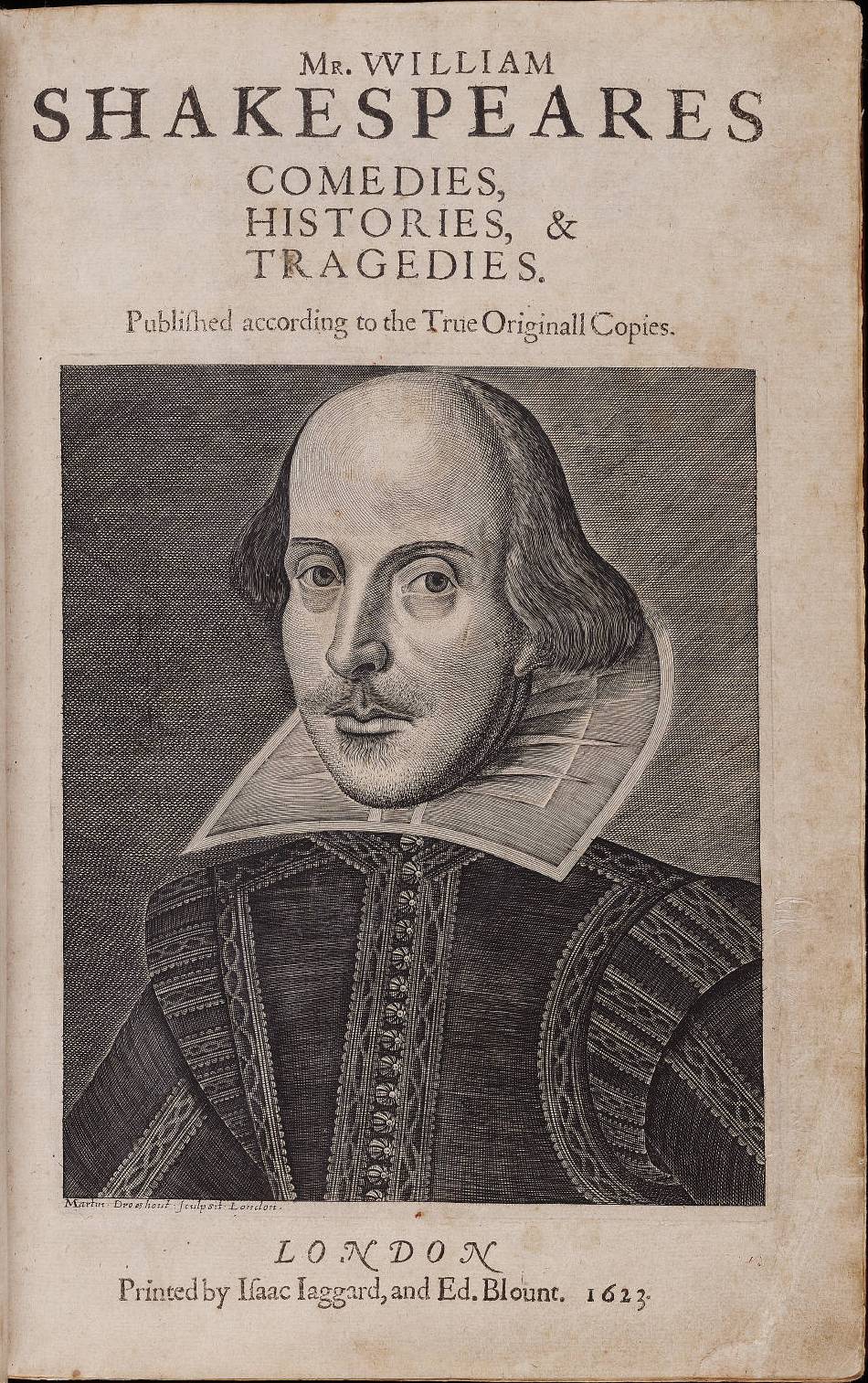

Shakespeare used “toy” over thirty times—never once meaning a child's plaything. For the Elizabethans, “toy” was a Swiss Army knife of a word: a fancy, a whim, an idle thought, a trifle, an ornament, a small gift, a romantic entanglement.

The First Folio (1623) — preserving Shakespeare's uses of 'toy'

Martin Droeshout, 1623. Public Domain.

Hamlet — 'These are but wild and whirling toys'

1603 Quarto edition. British Library. Public Domain.

“These are but wild and whirling toys.”

— Hamlet, 1601

Queen Elizabeth I — wealthy women wore 'toys' (ornamental jewelry)

Nicholas Hilliard, c. 1575. Walker Art Gallery. Public Domain.

Wealthy women wore “toys”—not playthings but jewelry, ornamental trinkets, decorative frivolities. Men dismissed women's concerns as “toys,” meaning matters of no consequence. The word lived in the space between desire and dismissal.

Crucially, “toy” in this era still belonged primarily to adults. Children had playthings—dolls, balls, hoops—but the English language rarely called them “toys.” That association was still forming, like a photograph developing in chemical baths.

William Shakespeare

Master of Semantic Range1564–1616- Used 'toy' 30+ times, never meaning 'child's plaything'

- His uses include: fancy, whim, ornament, trifle, idle imagination

- Demonstrates the word's breadth before semantic narrowing

“This is a very scurvy toy of Fortune's.”

Robert Cawdrey

The First Dictionary Makerc. 1538–1604- Compiled 'A Table Alphabeticall' (1604)—first English dictionary

- Captured early definitions showing 'toy' as trifle and ornament

- Preserved evidence of how Elizabethans understood common words

The Children's Claim

John Locke (1632–1704) — championed learning through play

Godfrey Kneller, 1697. Hermitage Museum. Public Domain.

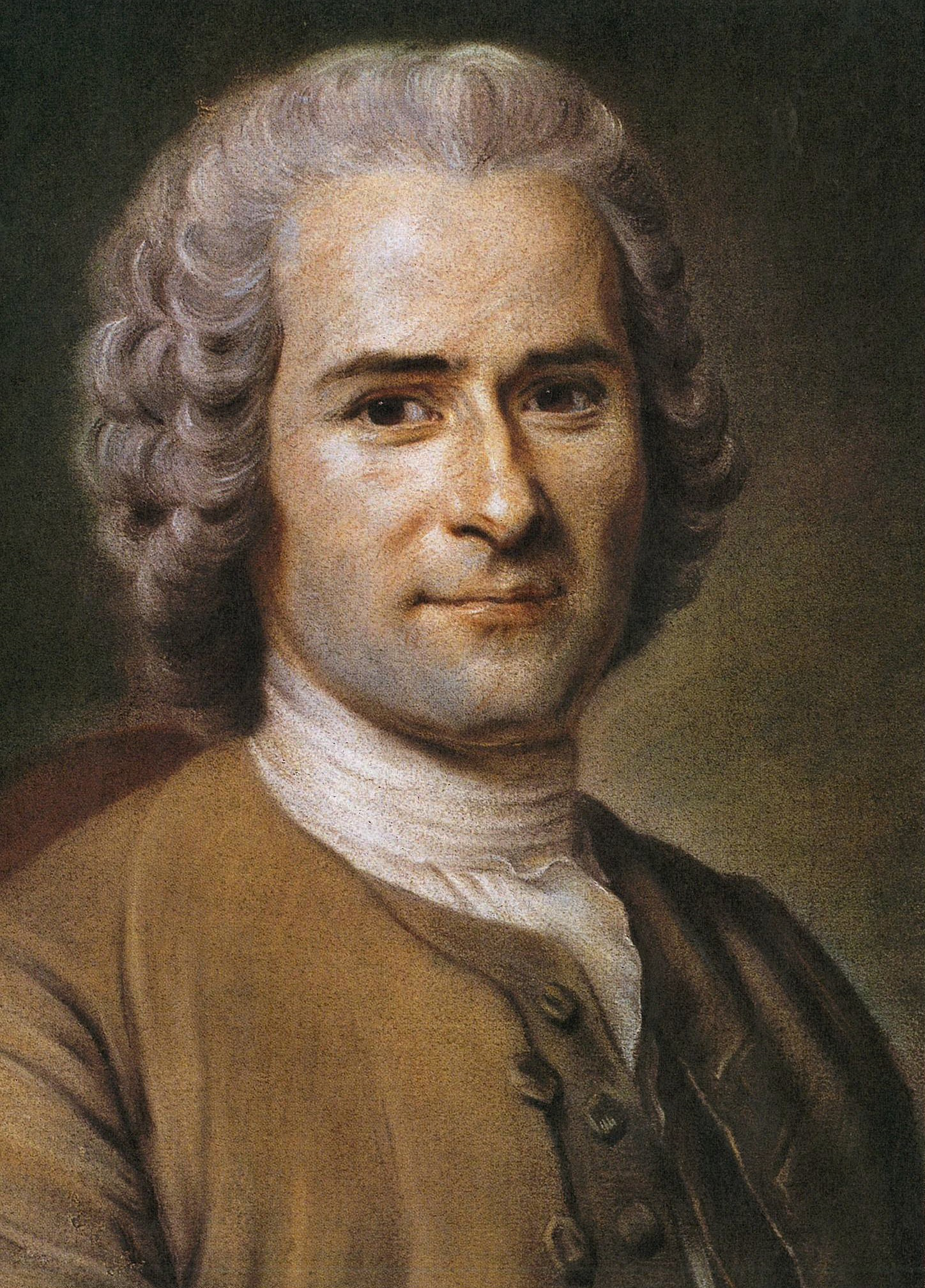

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) — revolutionized thinking about childhood

Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1753. Public Domain.

The 17th and 18th centuries invented childhood as we know it. Philosophers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that children were not miniature adults but a distinct category of human being—with distinct needs, including play.

As childhood crystallized as a concept, it required vocabulary. “Toy” was available.

Samuel Johnson (1709–1784) — his Dictionary captured 'toy' in transition

Joshua Reynolds, c. 1756. National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain.

A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) — defining 'toy' for the ages

Samuel Johnson, 1755. Public Domain.

Samuel Johnson's Dictionary (1755) still lists multiple meanings for “toy”—but the children's sense is rising. By century's end, “toy” increasingly meant what adults gave children: objects designed for play, for learning-through-amusement, for cultivating innocent joy.

L'Enfant au toton (1738) — Chardin captures childhood play

Jean-Siméon Chardin, 1738. Louvre Museum. Public Domain.

John Locke

Philosopher of Childhood1632–1704- Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693) emphasized learning through play

- Argued children should have playthings suited to their development

- Helped establish philosophical foundation for toys as educational tools

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Champion of Natural Play1712–1778- Émile (1762) revolutionized thinking about childhood

- Advocated for children's natural inclination to play as essential

- Influenced how society conceptualized childhood—and its objects

The Toymaker's Art

Nuremberg toys — the 'Toy Capital of the World' since the 18th century

Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Nuremberg claimed the title “Toy Capital of the World” by the 18th century. Generations of craftsmen—wood carvers, tin smiths, doll makers—transformed “toy” from dismissive noun to proud profession. When your family name was synonymous with toymaking, the word commanded respect.

The guild system elevated toy production to recognized craft. Master toymakers trained apprentices. Quality standards emerged. Toy fairs drew international buyers. What had been “trifles” were now serious business.

Nuremberg tin soldiers — when toymaking became a respected craft

Stadtmuseum Fembo-Haus, Nuremberg. Public Domain.

Wooden pull-along horse — the craft of Black Forest toymakers

Unknown maker, 19th century. Public Domain.

Puppenmacher (Doll Maker) — from Christoph Weigel's Ständebuch (1698)

Christoph Weigel, 1698. Public Domain.

The materials told stories: carved wood from the Black Forest, painted tin from Nuremberg, delicate porcelain dolls from Thuringia. Each material had its masters, each region its specialty. “Toy” absorbed the dignity of craft, the weight of tradition, the pride of expertise.

The Nuremberg Toymakers

Craftsmen Who Gave 'Toy' Weight16th–19th Century- Established Nuremberg as 'Toy Capital of the World' by 1700s

- Guild system elevated toymaking to recognized profession

- Exported tin soldiers, wooden figures, and mechanical toys worldwide

- Families like Märklin and Bing made 'toymaker' a proud identity

Industry and Innocence

A Victorian toy shop — where 'toy' became synonymous with childhood

From Mrs Leicester's School, 1885. Public Domain.

The Industrial Revolution transformed toys from handcraft to mass product. Factories in Germany, Britain, and America churned out tin soldiers, porcelain dolls, and mechanical wonders at unprecedented scale. Prices fell. Availability exploded. For the first time, toys reached beyond the wealthy.

Porcelain dolls — toys became objects of desire for children everywhere

V&A Museum, London. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Victorian Christmas traditions made toy-giving a ritual of love

Punch magazine, 1846. Public Domain.

Märklin locomotive — German toymaking reached industrial scale

Märklin, c. 1900. Public Domain.

Victorian sentiment wrapped “toy” in moral warmth. Childhood was sacred; toys were childhood's sacred objects. Christmas traditions made toy-giving a ritual of love. Department stores built cathedrals of consumerism with toy departments as their holy of holies.

By 1900, the semantic transformation was complete. “Toy” now meant, primarily and overwhelmingly, an object for children's play. The older meanings—trifle, ornament, dalliance—retreated to archaic status.

A.C. Gilbert

The Man Who Saved Christmas1884–1961- Invented the Erector Set (1913)—educational construction toy

- Olympic gold medalist who became toy magnate

- During WWI, lobbied Congress to exempt toy industry from war production

- Earned nickname 'The Man Who Saved Christmas' for ensuring toys remained available

“Hello, Boys! Make Lots of Toys!”

The Living Word

LEGO — from Danish 'leg godt' (play well), the world's most successful toy

Alan Chia, 2006. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The 20th century secured “toy” as a children's word—but the word refused to stay put. New compounds emerged: “toy soldier,” “toy car,” “toy poodle” (a dog bred small enough to be... toy-like?). “Sex toys” reclaimed the word's ancient association with adult pleasure. “Executive toys” colonized office desks.

The original Barbie (1959) — Ruth Handler's vision transformed 'toy' forever

Mattel, 1959. Fair use for educational purposes.

Toy poodle — even dog breeds carry the word now

Stuart Richards, 2012. CC BY 2.0.

Today, “toy” lives everywhere. It modifies nouns (toy car, toy gun), names entire industries, describes anything miniature or playful or not-quite-serious. The word that once meant “trifle” has become essential to billion-dollar commerce—the ultimate revenge of frivolity.

Ole Kirk Christiansen

The Block Builder1891–1958- Founded LEGO (from Danish 'leg godt' = 'play well')

- Created the world's most successful toy

- LEGO represents the enduring power of creative play

Ruth Handler

Barbie's Mother1916–2002- Co-founded Mattel; created Barbie (1959)

- Created the most successful doll in history

- Transformed 'toy' into cultural phenomenon

“Through the doll, the little girl could be anything she wanted to be.”

The Meaning of Play

Johan Huizinga (1872–1945) — 'Play is older than culture'

Unknown photographer. Public Domain.

Johan Huizinga, the Dutch historian, argued that play is older than culture itself. Animals play. Babies play before they speak. Play is not a break from life—it is essential to life. The word “toy” carries this weight now, but it didn't always.

Homo Ludens (1938) — the book that elevated play to philosophy

H.D. Tjeenk Willink & Zoon, 1938. Public Domain.

“Play is older than culture, for culture, however inadequately defined, always presupposes human society, and animals have not waited for man to teach them their playing.”

— Johan Huizinga, 1938

When “toy” meant “trifle,” society confessed its suspicion of play. When “toy” meant “ornament,” it revealed anxiety about frivolity. When “toy” finally settled on “children's plaything,” it both honored childhood and exiled adult play—giving children permission while implicitly denying it to adults.

To trace a word is to trace a culture's permission structures. What we call things reveals what we allow ourselves to want.

Johan Huizinga

Philosopher of Play1872–1945- Homo Ludens (1938) argued play is foundational to culture

- Elevated play from frivolity to fundamental human need

- His work reframed how scholars understand toys and games

Every time you say “toy,” seven centuries speak through you.

The word carries medieval scandal and Enlightenment philosophy, Victorian sentiment and modern commerce. A single syllable—and an entire history of humanity's relationship with play.

Sources & Further Reading

- Oxford English Dictionary - 'toy' entry

- Middle English Dictionary - University of Michigan

- Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture (1938)

- Sutton-Smith, Brian. The Ambiguity of Play (1997)

- Cross, Gary. Kids' Stuff: Toys and the Changing World of American Childhood

- V&A Museum of Childhood - Toy History Collection

- The Strong National Museum of Play - History of Toys

- Shakespeare's Use of 'Toy' - Folger Shakespeare Library

This narrative was researched using peer-reviewed etymological sources, historical dictionaries, and museum collections specializing in toy history.