The History of Languages

From the first human utterance to 7,000 living tongues—the story of how we learned to share our minds

The Dawn of Speech

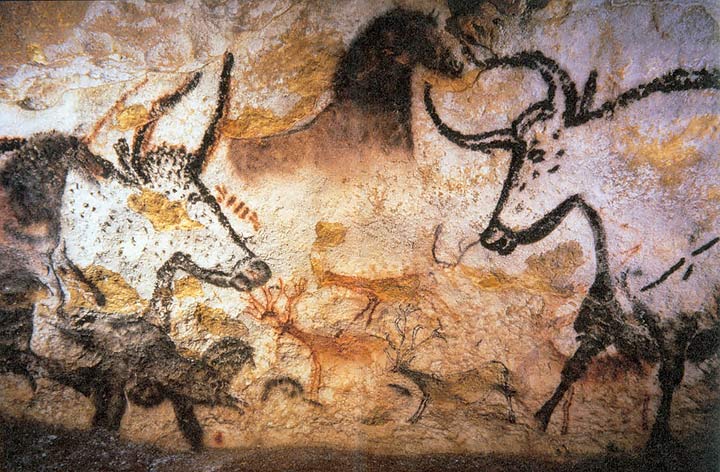

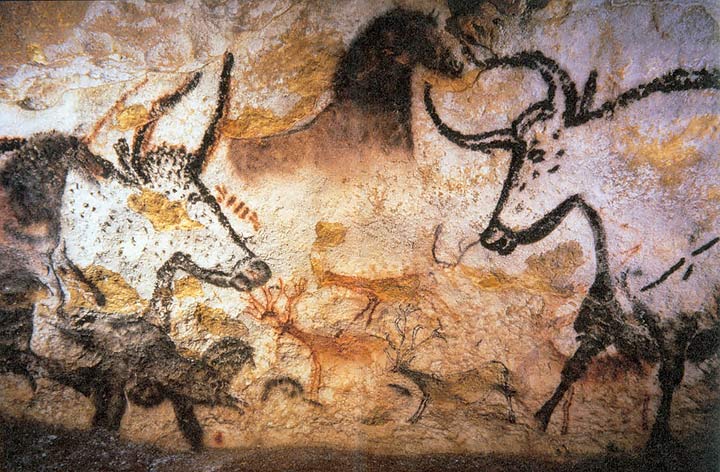

Picture a group of early humans huddled around a fire on the African savanna, perhaps 100,000 years ago. One points to the sky and makes a sound. Another understands. In that moment, the world changed forever.

We don't know what the first word was. We never will. But we know this: somewhere in our past, humans developed the ability to assign arbitrary sounds to meanings—and to share those meanings with others.

This wasn't just learning to communicate—animals do that. This was learning to think in symbols. To represent the world in sounds. To share not just “danger!” but “there was danger yesterday, at the river, and it might come back tomorrow.”

Language didn't just let us describe the world. It let us imagine worlds that don't exist—and then build them.

Scientists call this “recursion”—the ability to embed ideas within ideas, to say not just “the man” but “the man who saw the lion that killed the zebra that drank from the river.” No other species has this. It's what makes us human.

Language begins in Africa...

Humans migrate north, carrying their tongues...

Spreading across Asia and Europe...

Until every continent has voices.

The Invention of Writing

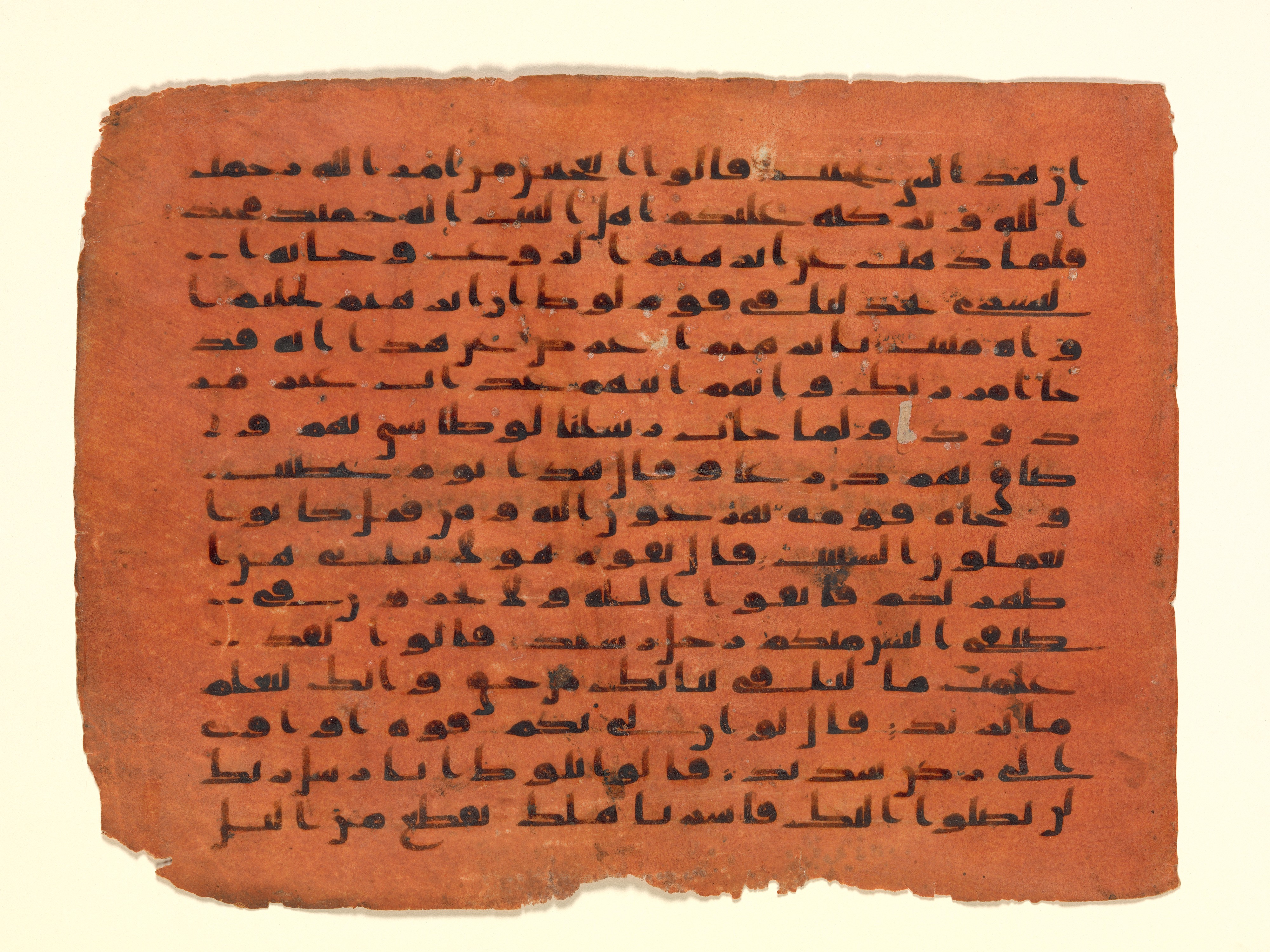

For 95,000 years, language existed only in the air. Words were spoken, heard, and gone. Everything that humans knew had to be memorized, passed from mouth to ear, generation after generation.

Then, around 3400 BCE in ancient Sumer (modern-day Iraq), someone pressed a wedge into wet clay. Writing was born.

The first writing wasn't poetry or philosophy—it was accounting. “Five goats delivered to the temple.” But once humans could record words, they quickly realized they could record ideas. Laws. Stories. Dreams.

Writing is frozen speech. It lets the dead speak to the living, and the living speak to the unborn.

Writing emerged independently in at least four places: Mesopotamia (cuneiform), Egypt (hieroglyphics), China (oracle bones), and Mesoamerica (Maya glyphs). Each developed its own logic, its own beauty.

Jean-François Champollion

The Man Who Unlocked Egypt- French scholar who deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphics in 1822

- Used the Rosetta Stone's three parallel texts as his key

- Dedicated his entire short life to this single puzzle

- Died at 41, having given humanity back 3,000 years of history

“I've got it!”

The Great Language Families

Here's a remarkable fact: English and Hindi are related. So are Persian and Swedish, Bengali and Portuguese. They all descend from a language spoken by nomads on the steppes of Central Asia about 6,000 years ago. We call it Proto-Indo-European.

No one knows exactly what Proto-Indo-European sounded like—it was never written down. But by comparing its descendants, linguists have reconstructed hundreds of words. The word for “mother” was something like *méh₂tēr—which became mater in Latin, mātar in Sanskrit, mother in English.

Indo-European is just one of hundreds of language families. Sino-Tibetanconnects Mandarin to Tibetan and Burmese. Niger-Congo links Swahili to Yoruba to Zulu—over 1,500 languages across Africa. Austronesian spreads from Madagascar to Hawaii, following ancient seafarers across the Pacific.

Indo-European

Europe, South Asia, Americas

Every language carries a world inside it—a way of seeing, a philosophy, a culture. When a language dies, a window on the universe closes forever.

Empires and Alphabets

Around 1050 BCE, Phoenician merchants along the Mediterranean developed something revolutionary: the alphabet. Instead of hundreds of symbols like Egyptian hieroglyphics or thousands like Chinese characters, they used just 22 marks— one for each consonant sound.

This idea spread like wildfire. The Greeks borrowed it, adding vowels. The Romans adapted the Greek version. Arabic developed its own. Today, most of the world's writing systems trace back to those Phoenician traders.

But the alphabet wasn't just about writing—it was about power. When Alexander the Great conquered the known world, Greek became the language of learning from Egypt to India. When Rome built its empire, Latin followed. The language of rulers became the language of the ruled.

Arabic spread with Islam from Spain to Indonesia. Sanskrit carried Hindu thought across Southeast Asia. Chinese characters were adopted by Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese scholars.

King Sejong the Great

The King Who Created an Alphabet- Ruled the Joseon Dynasty of Korea (1418-1450)

- Invented Hangul in 1443—a systematic alphabet for the Korean people

- Designed it to be easy to learn, so commoners could read

- Hangul is considered one of the most scientifically designed writing systems

“A wise man can acquaint himself with them before the morning is over; a stupid man can learn them in ten days.”

One Alphabet, Many Scripts

Each script adapted to fit its language...

Colonization and Change

In 1492, Columbus sailed west. Within a century, European powers had claimed vast territories across the Americas, Africa, and Asia. They brought guns, disease, missionaries—and their languages.

Spanish swept across Latin America. Portuguese took root in Brazil and along the coasts of Africa and Asia. English spread to North America, India, Australia, and beyond. French colonized parts of every continent.

This wasn't peaceful linguistic exchange. Colonial languages were often imposed by force. Children were punished for speaking their mother tongues in school. Indigenous languages were banned, mocked, erased.

And yet—languages resisted. They survived in homes, in songs, in secret. They blended with colonial tongues to create new languages: creoles and pidgins that belong to neither colonizer nor colonized, but to the communities that created them.

To speak another's language is to enter their world. To lose your own is to be exiled from your ancestors.

Endangered Voices

of the world's languages are endangered

Of the roughly 7,000 languages spoken today, half may vanish by the end of this century. The last fluent speakers are aging. Young people are switching to dominant languages like English, Mandarin, Spanish.

When a language dies, it's not just words that are lost. It's the unique knowledge encoded in those words—medicinal plants known only by their indigenous names, ecological wisdom passed down for millennia, oral histories that were never written down.

Ayapaneco

CriticalMexico

Njerep

CriticalNigeria/Cameroon

Ongota

CriticalEthiopia

Liki

CriticalIndonesia

Tanema

CriticalSolomon Islands

Chulym

Severely EndangeredRussia

Pawnee

CriticalUSA

Manx

RevitalizedIsle of Man

Every language is a unique solution to the puzzle of being human. When we lose one, we lose answers to questions we haven't yet learned to ask.

But there is hope. Communities worldwide are fighting to revive their languages. Welsh has grown from near-extinction to over half a million speakers. Hebrew was resurrected as a living language after being dormant for centuries. Maori immersion schools in New Zealand are creating a new generation of fluent speakers.

The Digital Age

The internet began in English. For years, the digital world was dominated by the Roman alphabet. But as the web expanded, so did its languages. Today, less than 60% of web content is in English—and that share is shrinking.

Something else remarkable has happened: emoji. These tiny pictures— first created by a Japanese phone company in 1999—have become the first truly universal pictographic communication system since Egyptian hieroglyphics.

The digital revolution has been both a threat and a lifeline for languages. On one hand, global platforms privilege major languages. On the other, technology offers unprecedented tools for preservation: voice recording, dictionary apps, online communities for scattered speakers.

And then there are programming languages—a new kind of language entirely. Python, JavaScript, SQL: languages designed not to communicate with other humans, but with machines. In a way, we're teaching our creations to understand us.

Artificial intelligence can now write poetry, translate languages, generate text—but it learned from us. Every word it knows was once spoken by a human.

The Universal Thread

After all this—after 100,000 years of speaking, 5,000 years of writing, after empires and extinctions and digital revolutions—what remains constant?

We all speak of the same things. Every language has words for mother and father, for water and fire, for love and death. Every language can express joy and sorrow, hope and fear. Every language can tell a story.

Linguists have discovered something remarkable: certain words are nearly universal. “Mama” sounds similar in hundreds of unrelated languages— not because they borrowed it from each other, but because it's one of the first sounds a baby can make, and mothers everywhere claimed it.

The word “huh?” appears in essentially the same form in every language ever studied—a universal expression of “what did you say?” We are not as different as we sometimes think.

Language is not what divides us. It is the proof that we are one species, endlessly creative, forever reaching out across the silence to connect.

7,000 languages. 8 billion speakers. One human family.

Every word you speak connects you to everyone who has ever spoken before—and everyone who will speak after.

Sources & Further Reading

Academic Sources

- Ethnologue: Languages of the World (24th edition)

- UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger

- The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language by David Crystal

- The Story of Human Language (Great Courses) by John McWhorter

- Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond

- The Power of Babel by John McWhorter

Research Organizations

- Linguistic Society of America

- UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage

- Endangered Languages Project (Google)

- The Language Conservancy

- Foundation for Endangered Languages

- Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

Digital Resources

- Glottolog 4.0 Language Database

- WALS Online (World Atlas of Language Structures)

- PHOIBLE (Cross-linguistic Phonological Database)

- Omniglot Writing Systems Encyclopedia