A Visual Essay

The Distance Between

How a pronged instrument became the measure of civilization itself

The Byzantine Bite

Constantinople, 4th–11th Century

The imperial court of Byzantium, where sweetness required separation

The fork's origin is not in hunger but in stickiness. Byzantine nobles faced a delicate problem: their beloved honey-soaked sweetmeats, their candied fruits and rose-water pastries, left fingers impossibly tacky. The solution was a tiny two-pronged spear—a personal tool for lifting the delicacy to the lips without soiling the hands.

Byzantine fork, gold with ivory handle, c. 950 CE

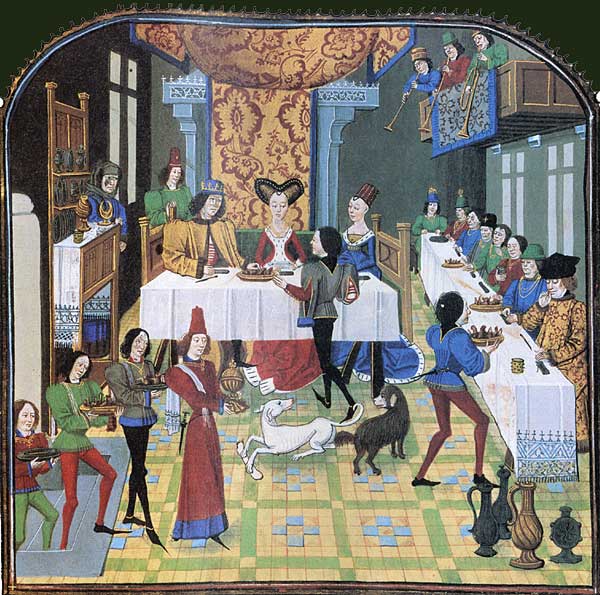

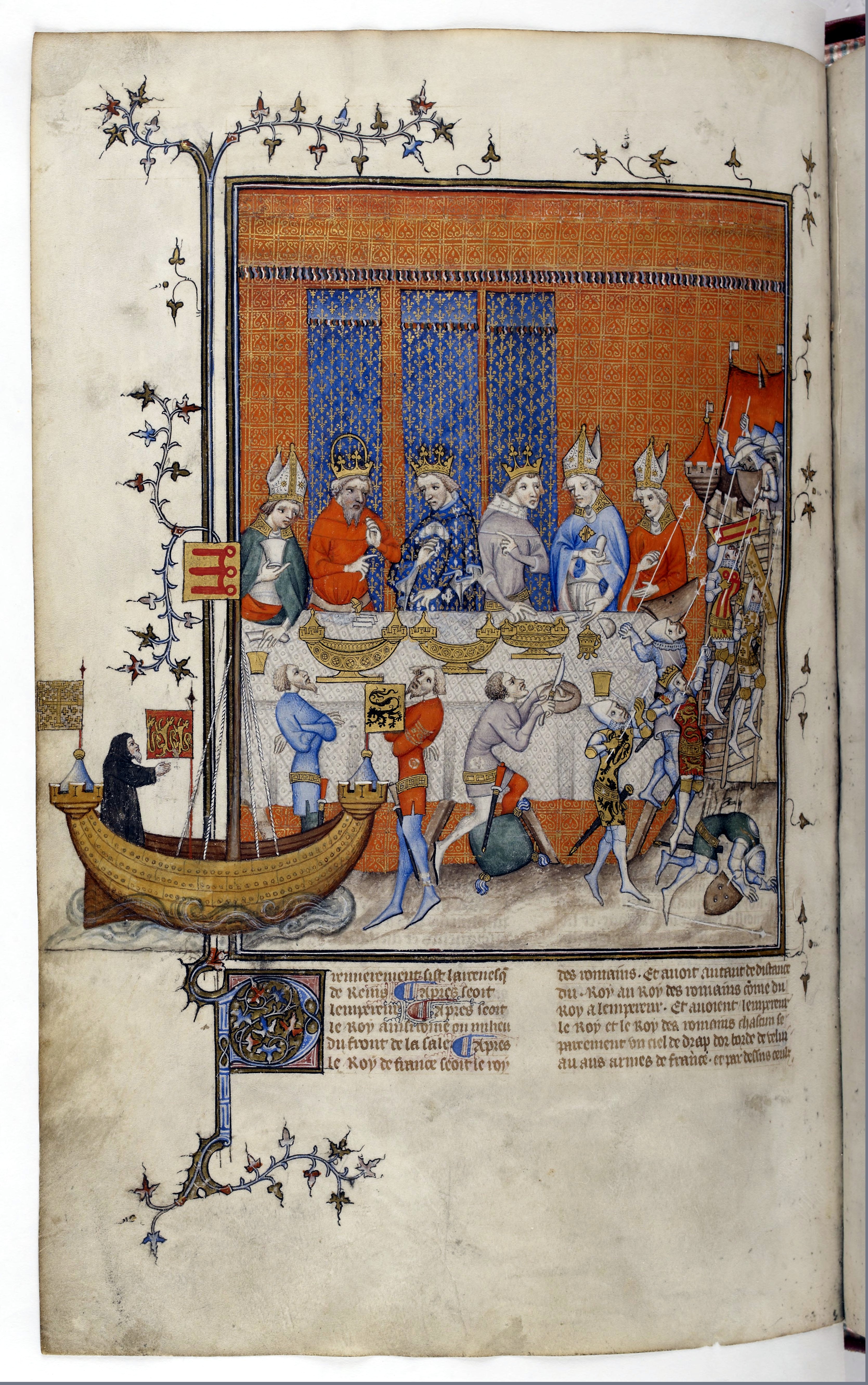

Imperial banquet scene from Byzantine manuscript

These were not humble implements. Byzantine forks were status symbols—gold, silver, ivory, studded with gems. They belonged to empresses and emperors, passed down through generations. The fork was the mark of a civilization that could afford to be fastidious.

The distance between hand and food measured the distance between appetite and refinement.

Theophanu

The Byzantine Bride

c. 955–991 CE

- Brought the fork to Western Europe through marriage to Holy Roman Emperor Otto II in 972

- Scandalized the German court by refusing to eat with her hands

- Her Greek customs were mocked as effeminate and vain

"She did not touch food with her fingers, but had servants cut it into small pieces, which she would pick up with a certain golden two-pronged instrument and carry to her mouth."

— Peter Damian, c. 1070

The Byzantine fork remained an Eastern secret for centuries. Western visitors to Constantinople noted these strange implements with curiosity but not adoption. The fork was as foreign as the silk, as exotic as the spices—admired but not imitated.

This would change with a single woman—and a single death.

The Devil's Instrument

Medieval Europe, 11th–15th Century

Marginalia demons with fork-like implements, 13th century

The fork arrived in Western Christendom like a whisper of heresy. When Princess Maria Argyropoulina, Byzantine bride of the Doge of Venice, brought her golden fork to Italy in 1004, the reaction was not curiosity but horror.

The clergy pronounced judgment: this was the devil's own instrument.

Nor did she deign to touch food with her fingers, but would command her eunuchs to cut it up into small pieces, which she would impale on a certain golden instrument with two prongs and thus carry to her mouth.

— Peter Damian, Cardinal, c. 1070

The condemnation was theological. God had given humans fingers—natural forks, divinely designed. To reject God's gift for a metal substitute was vanity, pride, and potentially satanic. When Maria died of plague two years after her arrival, churchmen pointed to her corpse as proof.

Cardinal & Doctor of the Church (1007–1072)

His fierce condemnation of the Byzantine princess's fork shaped Western attitudes for centuries. The fork, to him, was vanity made metal.

Medieval dining—hands, knives, bread. No forks in sight.

For nearly four hundred years, the fork remained rare in Western Europe. Medieval diners ate with knives, spoons, and fingers. Bread served as both food and utensil—trenchers soaked up sauces, chunks of bread conveyed morsels to the mouth.

The fork was trapped in purgatory—neither banned nor accepted, waiting for resurrection.

The Medici Touch

Renaissance Italy, 15th–16th Century

Paolo Veronese, 'The Wedding at Cana' (detail), 1563

Italy saved the fork. While Northern Europe still ate with fingers, Italian city-states—Venice, Florence, Rome—embraced the prong as a mark of sophistication. The Renaissance rediscovered antiquity, and with it, a hunger for civilization.

The fork fit perfectly.

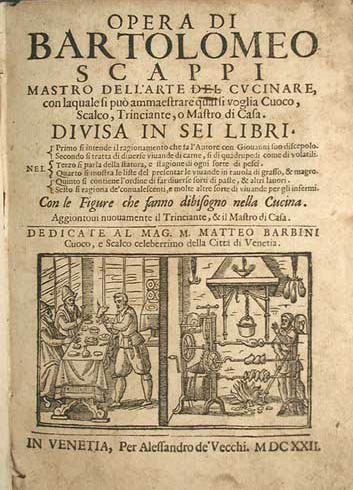

From Bartolomeo Scappi's 'Opera', 1570—forks as standard kitchen equipment

In 15th-century Italy, to eat with a fork was to declare oneself cultured, refined, humanist. Italian travelers were mocked abroad for their "effeminate" utensils, but they persisted. Venetian glassworkers created exquisite handles. Florentine silversmiths crafted ever-more elaborate designs.

Catherine de' Medici

The Fork's Ambassador

1519–1589

- Florentine noblewoman who became Queen of France

- Married Henry II at age 14, bringing Italian customs to French court

- Introduced the fork, modern cuisine, and table etiquette to France

- Mother of three French kings

"The queen eats in the Italian manner."

— French courtier, c. 1540

The great leap came with a wedding. In 1533, fourteen-year-old Catherine de' Medici arrived in France to marry the future King Henry II. She brought her Florentine entourage—including cooks, pastry chefs, and a full set of personal forks.

The French court was scandalized and fascinated in equal measure.

What was shocking became expected. What was Italian became French. What was royal became aspiration.

The English Curiosity

England, 16th–17th Century

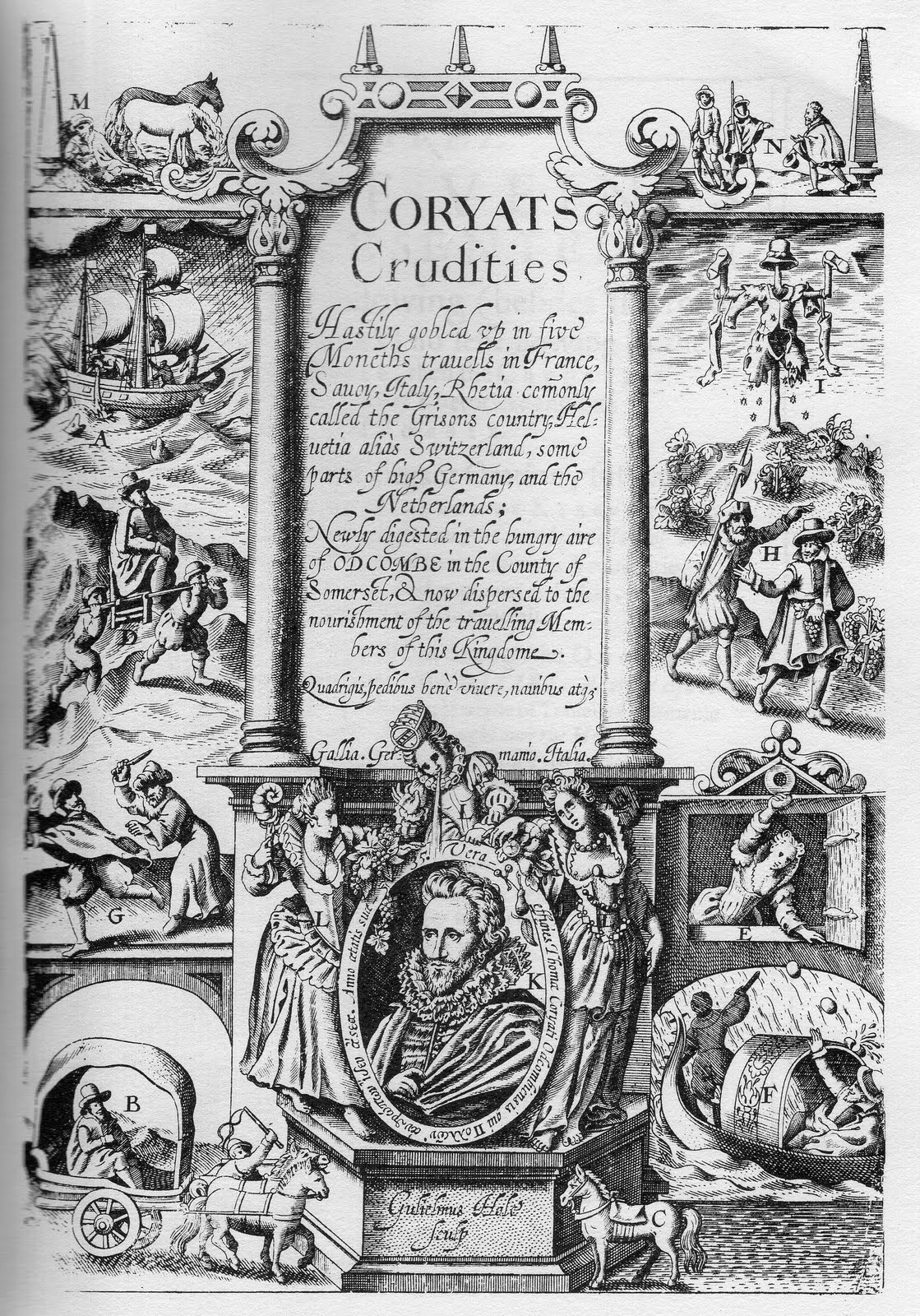

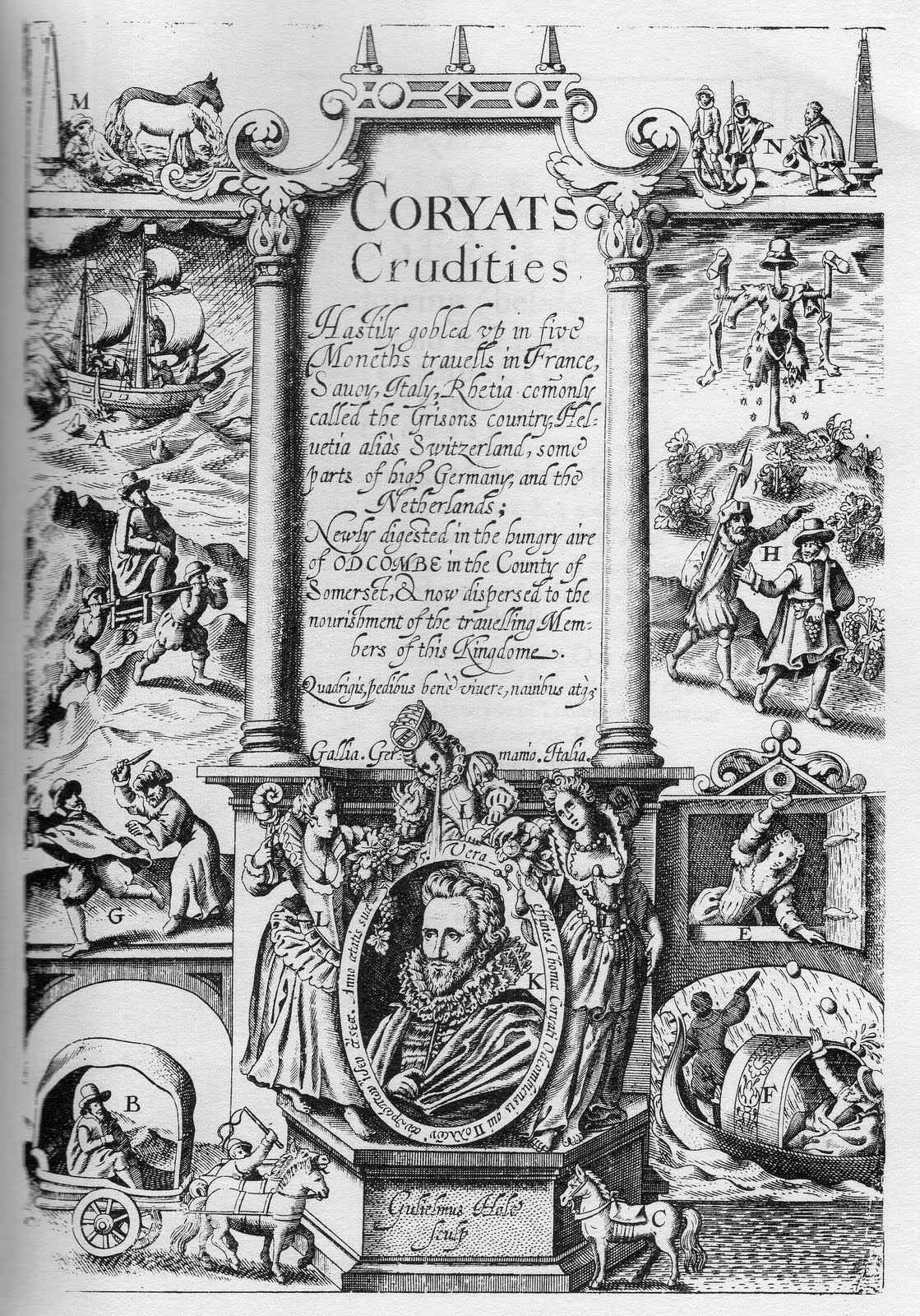

Coryat's Crudities, 1611—the first English guide to Continental manners

Thomas Coryat was an eccentric. A court jester, travel writer, and shameless self-promoter, he walked across Europe in 1608 and returned with tales that astonished his countrymen. Among them: the Italian fork.

The Italian cannot by any means endure to have his dish touched with fingers, seeing all men's fingers are not alike clean.

— Thomas Coryat, 1611

Thomas Coryat

The Fork's English Champion

1577–1617

- English travel writer and eccentric

- Walked across Europe recording observations

- First Englishman to extensively describe and advocate fork use

- Mocked as 'Furcifer' (fork-bearer/rascal) by his contemporaries

Latin: fork-bearer — but also rascal, gallows-bird

The pun delighted Coryat's critics. He persisted anyway.

English court dining, early 17th century

Within a generation, the English aristocracy began importing Italian forks. The island's resistance was crumbling. What begins in laughter often ends in imitation.

The eccentric's affectation became the gentleman's requirement.

The Industrial Appetite

18th–19th Century

Victorian-era flatware—the fork democratized

For a thousand years, the fork was a luxury. Gold, silver, ivory—materials that marked their owners as elite. The Industrial Revolution changed everything.

Sheffield, England, became the crucible of culinary democracy.

Matthew Boulton

The Industrialist's Fork

1728–1809

- Birmingham manufacturer and entrepreneur

- Pioneered industrial silver plating (Sheffield plate)

- Made silverware affordable for the middle class

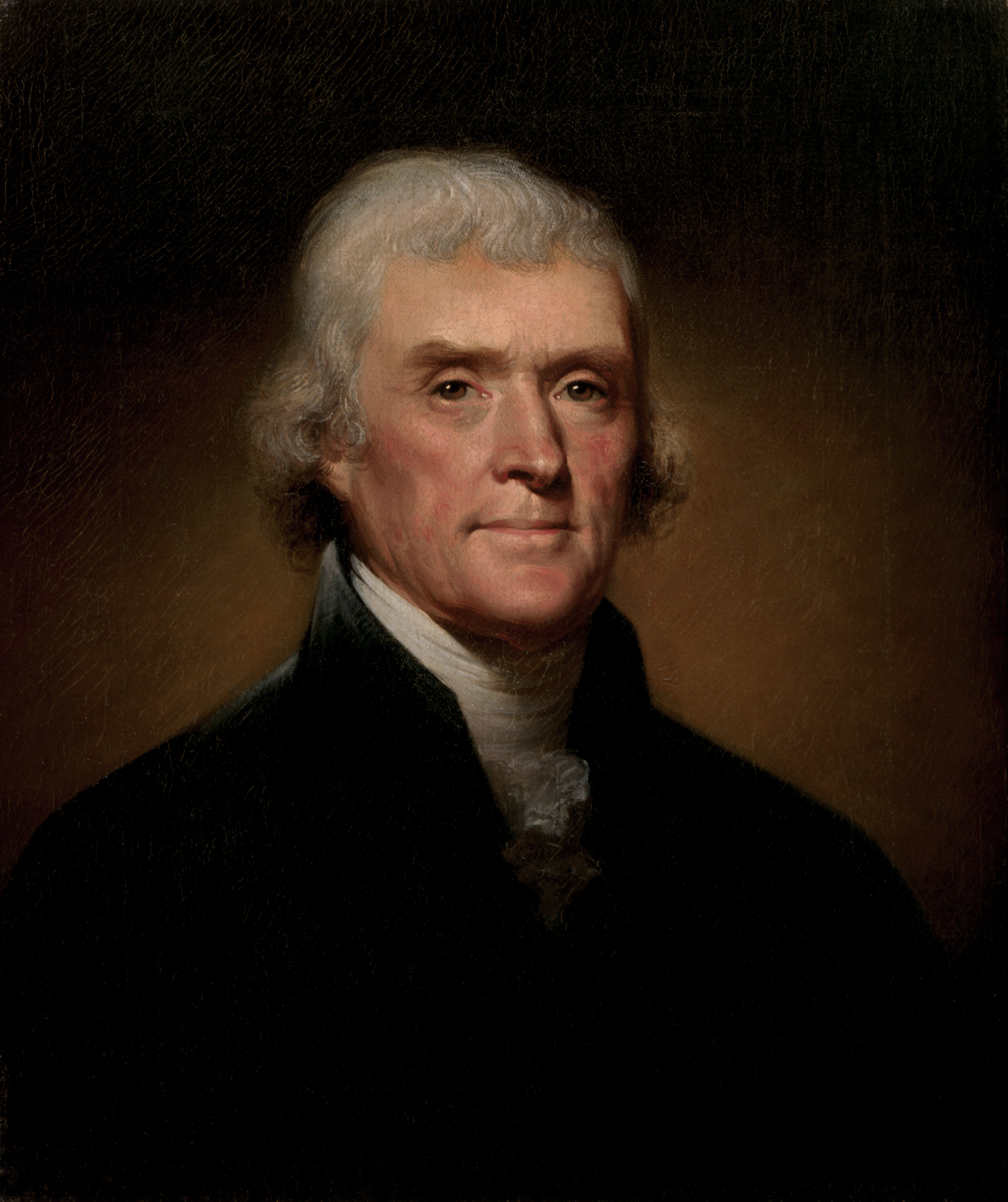

Thomas Jefferson

America's Fork Advocate

1743–1826

- Third U.S. President

- Encountered French fork customs as ambassador

- Returned with sophisticated dining habits

Mass-produced steel forks, c. 1880—luxury becomes standard

New alloys, new manufacturing techniques, new economies of scale. The first inexpensive steel forks appeared—rough by aristocratic standards but functional. The middle class could now set a proper table.

America accelerated the democratization. Young, ambitious, lacking Europe's feudal table manners, Americans embraced the fork with practical enthusiasm.

The fork's journey from Byzantine court to working-class kitchen was complete.

The Four-Tined Triumph

19th–20th Century

Georg Jensen Blossom pattern—modernism meets tradition

The four-tined fork became standard in the early 19th century, and then— remarkably—stopped changing. The design was perfected. Two thousand years of evolution reached its terminus in a simple, elegant form.

Spears, but cannot scoop

Better, but still unstable

Pierce, scoop, lift, stabilize—perfect

Emily Post

The Arbiter of Proper Use

1872–1960

- American author and etiquette authority

- Her 'Etiquette' (1922) codified American dining customs

- Made explicit what had been implicit—the rules of the table

"The fork is held with the handle in the palm, the tines curving downward."

Emily Post, 1912—the codifier of American table manners

With form fixed, the fork became a canvas for meaning. Etiquette codified its use—hold it this way, not that way; switch hands (American) or don't (Continental). Designers reimagined its aesthetics without changing its function.

Georg Jensen

The Fork as Art

1866–1935

- Danish silversmith and designer

- Created iconic modernist flatware

- Proved the fork could be functional art

The mathematics of eating had been solved. Now began the endless refinement of meaning.

The Global Table

Present DayThe fork conquered Western tables. But what of the rest of the world?

Western

Fork, knife, spoon. Individual portions. Distance from food.

East Asian

Chopsticks: 5,000 years old. No cutting at the table—that's for the kitchen.

South Asian

Each finger channels different energy. The fork interrupts that flow.

Ethiopian

Injera is utensil. Eating from a common plate is not poverty—it is intimacy.

The fork, then, is not universal progress but cultural choice. It embodies Western values: individuality, hygiene anxiety, the separation of self from food, the primacy of visual over tactile experience.

To eat with a fork is to hold the world at arm's length.

There is no "right" way to eat. Only the way each culture chose.