Rock & Roll

The Noise That Remade the World

It converged.

The Convergence

Before the Name: Multiple Streams Toward a Single Sound

“All this new stuff they call Rock and Roll, why I've been playing that for years now.”Sister Rosetta Tharpe, 1957

Who invented rock and roll? It's the question everyone asks, and it's the wrong question. Rock and roll was not invented—it converged. At least six distinct streams of African American musical innovation merged in the late 1940s, powered by new technologies and reaching across racial lines.

Boogie-woogie piano from Texas lumber camps. Jump blues from Kansas City and New York. Electric blues electrifying the Delta sound in Chicago. Gospel driving sacred music with rock rhythms. Rhythm & Blues as an industry category replacing 'race records.' Western swing from cross-racial Texas dance halls.

Each stream had its own masters, techniques, and regional character. When they converged—when amplifiers got loud enough, when tape recorders captured the energy, when radio waves crossed state lines and segregation barriers—they became something the world had never heard before.

Public Domain

Public DomainSister Rosetta Tharpe

The Godmother of Rock and Roll

1915–1973First gospel recording star; pioneered electric guitar distortion. Her 1944 'Strange Things Happening Every Day' was the first gospel song to reach the R&B Top 10.

“All this new stuff they call Rock and Roll, why I've been playing that for years now.” — 1957

William P. Gottlieb, Public Domain

William P. Gottlieb, Public DomainLouis Jordan

Father of Rhythm & Blues

1908–1975Alto saxophonist and bandleader with 57 R&B chart hits and 113 weeks at #1 between 1943 and 1950. His Tympany Five dominated the decade.

“Rock and roll would have never happened without him.” — Doc Pomus

Rivers Before the Flood

The Pre-Rock Streams (1920s–1949)

Before rock and roll had a name, Black women were creating its vocabulary. Ma Rainey—the 'Mother of the Blues'—began recording in 1923, her raw power and stage presence inventing the template for everything that followed. Her protégé Bessie Smith became the highest-paid Black entertainer of the 1920s, selling millions of records with a vocal intensity that would echo through every rock singer who ever screamed into a microphone.

In Texas lumber camps of the 1870s, African American pianists developed a driving style—eight-to-the-bar left-hand patterns beneath improvised right-hand melodies. The music migrated to Chicago, where Pinetop Smith's 'Pinetop's Boogie Woogie' (December 29, 1928) became the first hit with 'boogie' in the title.

On December 23, 1938, boogie-woogie reached Carnegie Hall. The 'Spirituals to Swing' concert featured Meade 'Lux' Lewis, Albert Ammons, and Pete Johnson. Classical America heard the rolling thunder.

Meanwhile, T-Bone Walker picked up the electric guitar in 1935 and invented its vocabulary—single-string phrases, double-string slurs, showmanship like playing behind his head. When Muddy Waters moved from Mississippi to Chicago in 1943, he faced a problem: acoustic Delta blues couldn't compete with Chicago's noisy clubs. The Delta blues became electrified, loud enough to shake walls.

Public Domain

Public DomainMa Rainey

Mother of the Blues

1886–1939The first great professional blues vocalist. Began recording in 1923 for Paramount Records; over 100 recordings. Mentored Bessie Smith. Her raw power, gold teeth, and elaborate stage presence created the template for rock stardom itself.

“They hear it come out, but they don't know how it got there.”

Carl Van Vechten, Public Domain

Carl Van Vechten, Public DomainBessie Smith

Empress of the Blues

1894–1937The highest-paid Black entertainer of the 1920s. Columbia Records' best-selling artist. Her vocal power—singing to thousands without a microphone—created the emotional intensity that defines rock singing. Every screamer traces back to Bessie.

“I ain't good-lookin', but I'm somebody's angel child.”

Pinetop Smith

First Boogie-Woogie Recording Star

1904–1929Recorded 'Pinetop's Boogie Woogie' (December 29, 1928), the first recording with 'boogie' in the title. Died from a gunshot wound in a Chicago dance-hall fight at age 24.

Heinrich Klaffs, CC BY-SA 2.0

Heinrich Klaffs, CC BY-SA 2.0T-Bone Walker

Electric Blues Guitar Pioneer

1910–1975First blues guitarist to make electric guitar a solo centerpiece (1935). Invented the vocabulary: single-string phrases, double-string slurs, playing behind his head.

“I thought 'Jesus Himself had returned to earth playing electric guitar.'” — B.B. King

The Impossible Question

What Was the First Rock and Roll Record? (1944–1951)

The search for rock's 'first record' is impossible to resolve definitively—and the attempt reveals how we construct origin myths. 1944: Sister Rosetta Tharpe's 'Strange Things Happening Every Day'—gospel with electric guitar distortion, crossing to the secular R&B chart. 1947: Roy Brown's 'Good Rockin' Tonight'—the word 'rock' used musically rather than sexually. 1949: Fats Domino's 'The Fat Man'—first rock record to sell one million copies.

Then there's 1951: 'Rocket 88' by Jackie Brenston with Ike Turner's Kings of Rhythm. Often cited as the first rock and roll record. Features distorted guitar—Willie Kizart's amplifier broke en route to Sun Studio; Sam Phillips stuffed newspaper in the cone to stop rattling, creating the first recorded distortion.

Nick Tosches wrote: 'It is impossible to discern the first modern rock record, just as it is impossible to discern where blue becomes indigo in the spectrum.' The impossibility of the question reveals the truth: rock emerged from a continuum of Black musical innovation. There was no single moment, no single inventor. There was a convergence.

Fats Domino

New Orleans' Gentle Giant

1928–2017Record sales in the 1950s-60s rivaled only by Elvis Presley; 65 million records sold. 'The Fat Man' (1949) was the first rock record to sell 1 million copies.

“Rock 'n roll is nothing but rhythm and blues, and we've been playing it for years down in New Orleans.”

Rob Mieremet, CC0

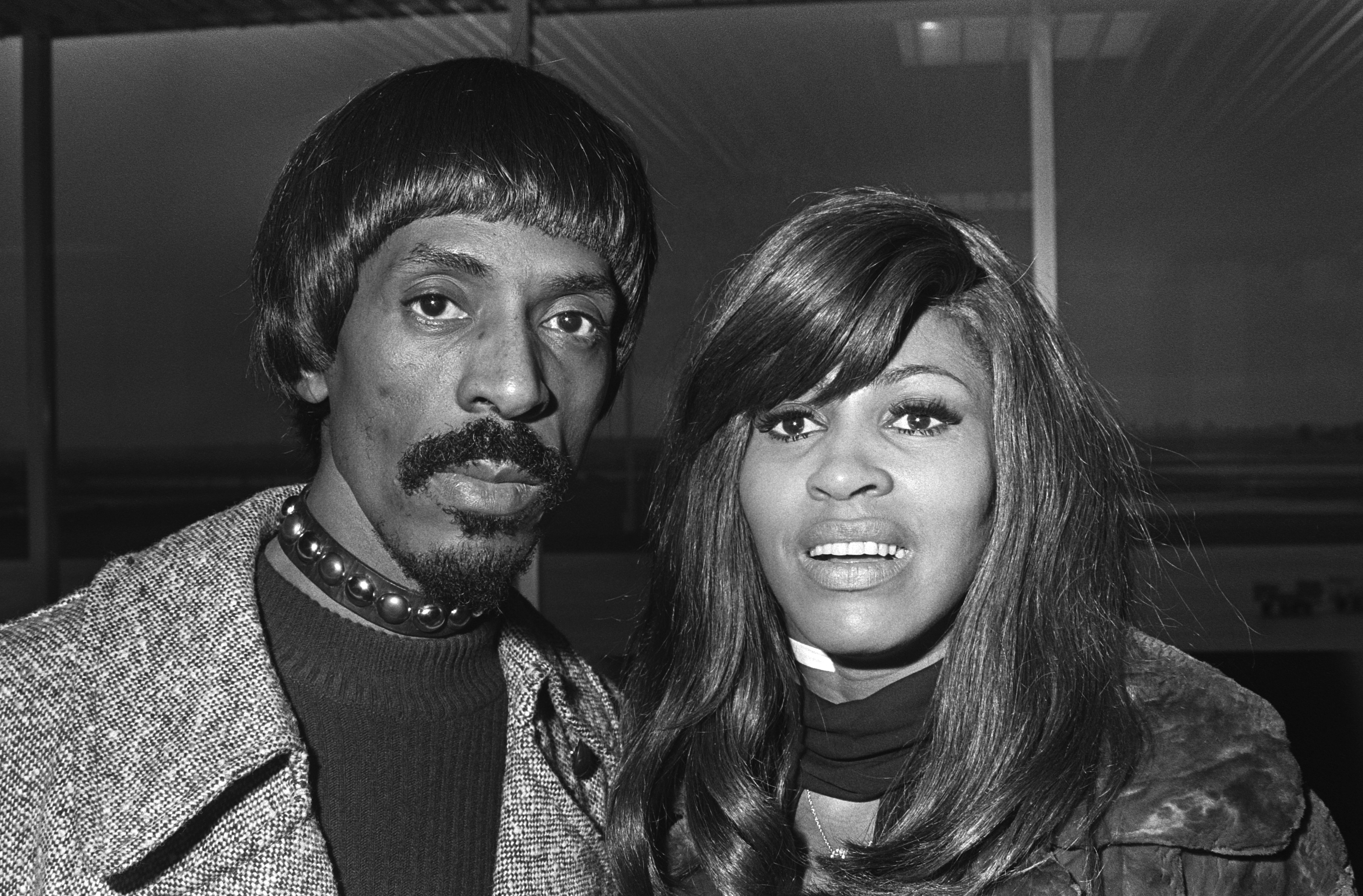

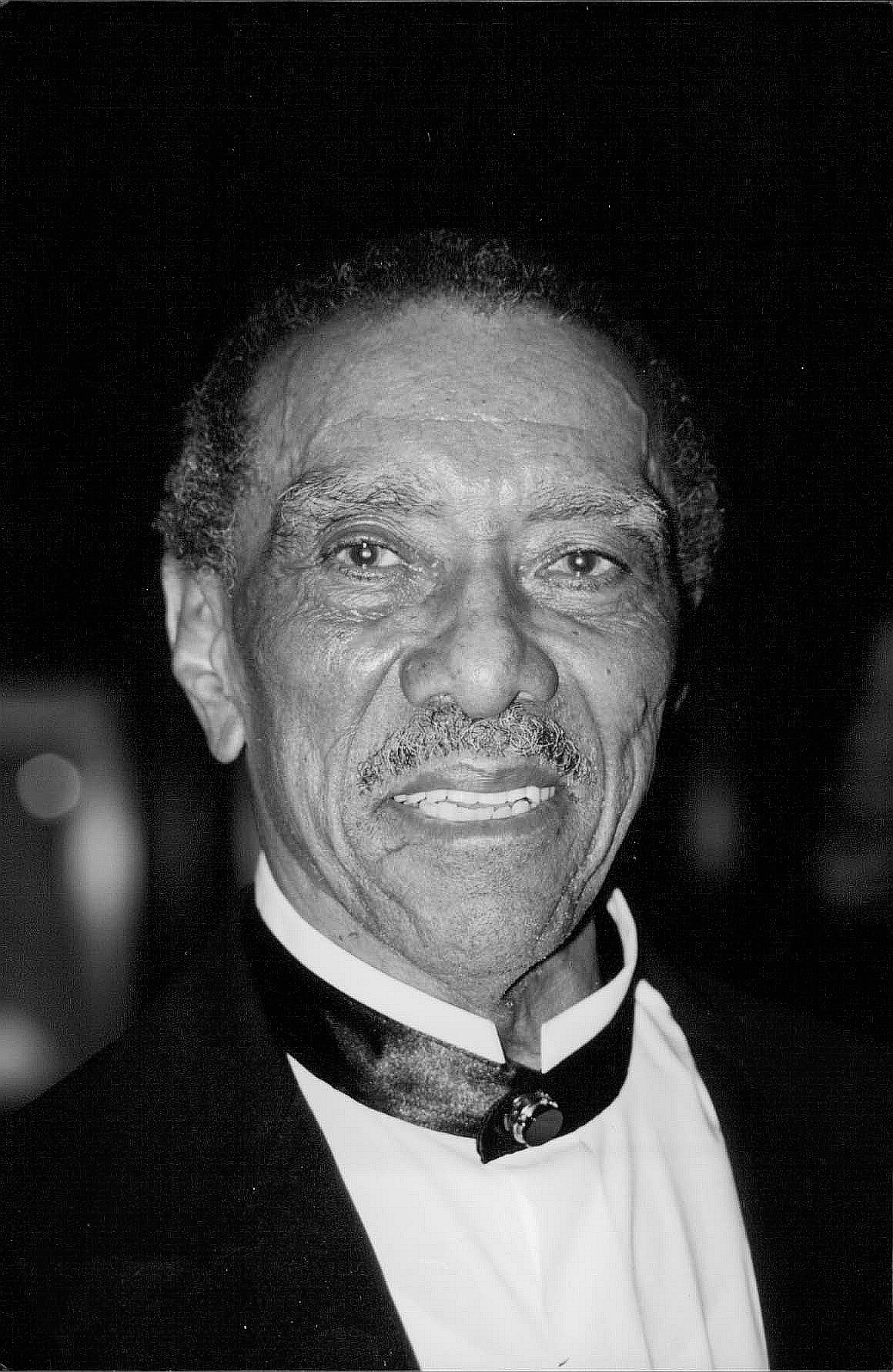

Rob Mieremet, CC0Ike Turner

Architect of 'Rocket 88'

1931–2007Led the Kings of Rhythm; wrote and arranged 'Rocket 88' though Jackie Brenston got vocal credit. Sam Phillips called him 'the most talented person he ever worked with.'

Nationaal Archief, CC0

Nationaal Archief, CC0Tina Turner

The Voice of the Revue

1939–2023As Anna Mae Bullock, she joined Ike Turner's Kings of Rhythm in 1957. The Ike & Tina Turner Revue became one of the most electrifying live acts of the 1960s. 'River Deep – Mountain High' (1966) was a masterpiece. Behind the stage, she endured years of abuse.

“I didn't have anybody, really, no foundation in life, so I had to make my own way.”

The Naming

Alan Freed and the Word 'Rock and Roll' (1951–1952)

The music existed before the name. African American artists and audiences knew what they were hearing. But for the music to cross the racial divide, it needed a new vocabulary.

Leo Mintz ran Record Rendezvous in Cleveland. In the late 1940s, he noticed something strange: white teenagers were coming into his store to buy R&B records marketed to Black audiences. They were dancing to music not meant for them. Mintz saw opportunity.

He approached local DJ Alan Freed with an idea: a radio show featuring this music, pitched to white teenagers. On July 11, 1951, Freed debuted 'The Moondog Rock 'n' Roll Party' on WJW Cleveland. The term 'rock and roll' had existed in Black culture for decades. Freed didn't invent it; he appropriated it, sanitizing the term for white consumption.

On March 21, 1952, Freed organized the Moondog Coronation Ball at Cleveland Arena—capacity 10,000. Over 20,000 people showed up. The fire department shut it down after one song. It was the first major rock and roll concert—and it nearly ended before it began.

Alan Freed

Moondog—Rock's First DJ Champion

1921–1965Popularized 'rock and roll' on radio starting July 11, 1951. Organized the Moondog Coronation Ball (March 21, 1952)—the first major rock concert. Destroyed by payola scandal; died penniless at 43.

“When the dance was stopped, I went off and cried. I'm not ashamed to admit it.”

The Electric Revolution

Technology as Co-Author (1935–1959)

Rock and roll was not just performed with new technologies—it was constituted by them. The physics of solid-body guitars, the electronics of tube amplifiers, the economics of 45 RPM singles: these shaped the music's fundamental character.

The acoustic guitar's hollow body created feedback when amplified. Leo Fender—who never learned to play guitar—solved this with a solid slab of wood: the Broadcaster (later Telecaster, 1950) and Stratocaster (1954). The solid body eliminated feedback and enabled volume. Rock's aggression became possible.

When vacuum tube amplifiers were pushed past their intended limits, they distorted the signal. This 'flaw' became rock's signature sound. The 45 RPM single (1949) made records affordable for teenagers and shaped song structure—rock songs had to be short, immediate, impactful. The Regency TR-1 transistor radio (1954) let teenagers listen privately, away from parents. Rock became youth property.

Mr. Littlehand, CC BY 2.0

Mr. Littlehand, CC BY 2.0Leo Fender

Solid-Body Guitar Creator

1909–1991Created the first mass-produced solid-body electric guitar (Telecaster, 1950; Stratocaster, 1954). Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee (1992). Never learned to play guitar.

Public Domain

Public DomainSam Phillips

Sun Records Founder

1923–2003Produced 'Rocket 88,' discovered Elvis, invented the slapback echo technique using two Ampex 350 tape recorders. First non-performer inducted into Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (1986).

“I knew that for black music to come to its rightful place in this country, we had to have some white singers come over and do black music.”

The Crescent City Sound

New Orleans: The Rhythmic Foundation (1945–1960)

New Orleans gave rock and roll its rhythm. The city's unique musical culture—blending Caribbean, African, French, and American traditions—produced the backbeat that would define the music.

Drummer Earl Palmer is 'correctly identified as the man who put the backbeat in rock 'n' roll'—emphasizing beats 2 and 4 rather than 1 and 3. This rhythmic innovation, rooted in New Orleans second-line tradition, became rock's defining pulse.

Cosimo Matassa opened J&M Recording Studio at 838 North Rampart Street in 1945. In just 15 x 16 feet, he captured virtually every New Orleans R&B hit from the late 1940s through the early 1970s. Producer Dave Bartholomew and artist Fats Domino created over 40 Top 10 R&B hits together. Their partnership defined the New Orleans sound.

Kingkongphoto, CC BY-SA 2.0

Kingkongphoto, CC BY-SA 2.0Earl Palmer

The Man Who Put the Backbeat in Rock 'n' Roll

1924–2008Drummer on Little Richard's 'Tutti Frutti,' Fats Domino's hits, and countless others. Session musician on over 250 records. Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee (2000).

“I wasn't thinking about inventing anything. I was just playing what felt right.”

WhyArts, CC BY-SA 4.0

WhyArts, CC BY-SA 4.0Cosimo Matassa

New Orleans Recording Engineer

1926–2014Captured virtually every New Orleans R&B hit from the late 1940s through early 1970s at J&M Studio. Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee (2012).

“The sound was in the room, not in the equipment.”

Where the Soul Was Recorded

Memphis and Sun Studio (1950–1959)

Memphis was where the races met in music—not without tension, not without exploitation, but with revolutionary results. Sam Phillips opened Memphis Recording Service (later Sun Studio) at 706 Union Avenue on January 3, 1950.

In August 1953, an 18-year-old truck driver paid $4 to record a demo for his mother. Elvis Presley's voice impressed Marion Keisker, Phillips's assistant. A year later, on July 5, 1954, Elvis returned to the studio. After hours of frustrating attempts at ballads, he started fooling around with Arthur Crudup's 'That's All Right.'

Phillips recognized the sound immediately. On July 7, 1954, DJ Dewey Phillips played 'That's All Right' on WHBQ Memphis. The phone lines exploded. A white boy singing Black music—not imitating, not sanitizing, but inhabiting it. The crossover began.

MGM, Public Domain

MGM, Public DomainElvis Presley

The King—The Crossover

1935–1977Bridged Black and white music for a mass audience. Over 1 billion records sold worldwide. His Sun Studio recordings changed American music.

“A lot of people seem to think I started this business. But rock 'n' roll was here a long time before I came along. Nobody can sing it like colored people.” — 1957

Maurice Seymour, Public Domain

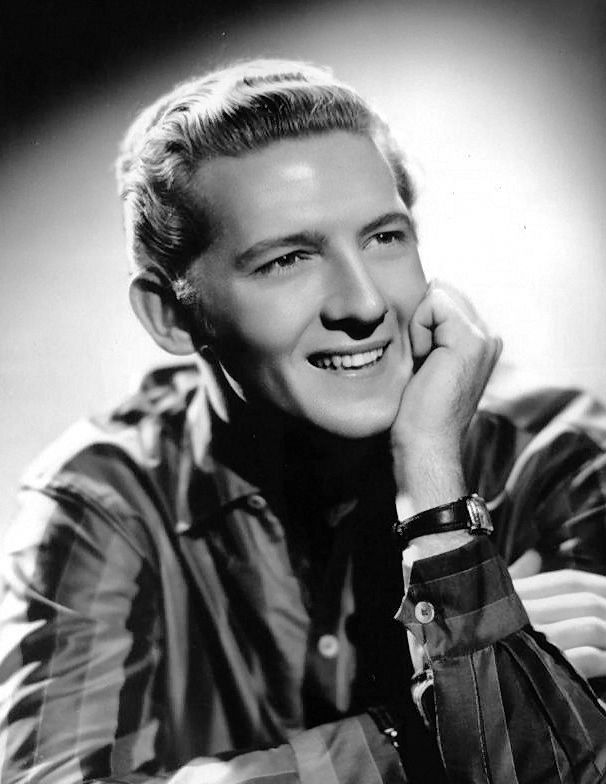

Maurice Seymour, Public DomainJerry Lee Lewis

The Killer

1935–2022Wild piano style; 'Whole Lotta Shakin' Going On' (1957), 'Great Balls of Fire' (1957). Career derailed by marriage to 13-year-old cousin (1958).

“Rock and roll is not a sin. Some of the people who play it are sinners.”

Public Domain

Public DomainWanda Jackson

The Queen of Rockabilly

b. 1937Toured with Elvis in 1955–56; he encouraged her to sing rockabilly. Her growling vocals on 'Fujiyama Mama' and 'Let's Have a Party' were harder than any man's. The only woman in 1950s rockabilly's front ranks.

“Elvis told me, 'You need to stop singing country and sing rock and roll.' So I did.”

The House That Blues Built

Chicago and Chess Records (1950–1969)

When the Delta blues came to Chicago, it got loud. Leonard Chess (born Lejzor Czyz) and Phil Chess (born Fiszel Czyz)—Polish Jewish immigrants—owned nightclubs on Chicago's South Side where bluesmen performed. In 1950, they founded Chess Records. At 2120 South Michigan Avenue, they built a catalog that defined electric blues.

Muddy Waters brought the Delta blues north and plugged it in. His 1958 UK tour shocked British audiences—electric blues at volume levels they'd never experienced. He planted seeds that would grow into the British Invasion.

Chuck Berry was the complete package: guitar innovation, lyrical wit, showmanship, and business sense. 'Maybellene' (1955) was his breakthrough—#1 R&B, #5 Pop. But Berry lost royalties for 31 years. Alan Freed demanded co-writing credit as payment for radio play. Berry didn't regain full ownership until 1986.

Public Domain

Public DomainChuck Berry

Rock's Supreme Poet

1926–2017'Maybellene' (1955) moved Chess from R&B into mainstream rock. Lost royalties for 31 years when Alan Freed was added to writing credits.

“It used to be called boogie-woogie, it used to be called blues, it used to be called rhythm and blues... It's called rock now.”

Jean-Luc Ourlin, CC BY-SA 2.0

Jean-Luc Ourlin, CC BY-SA 2.0Muddy Waters

Father of Modern Chicago Blues

1913–1983Recorded by Alan Lomax for Library of Congress (1941-1942). Electrified Delta blues in Chicago. His 1958 UK tour inspired the British Invasion.

“When I went into the clubs, the first thing I wanted was an amplifier.”

Chess Records, Public Domain

Chess Records, Public DomainEtta James

The Matriarch of R&B

1938–2012Signed to Chess subsidiary at 17. 'At Last' became timeless. Bridged R&B, blues, and rock with raw emotional power across six decades. Battled addiction, came back stronger. Six Grammys, Rock Hall 1993.

“I'm a woman. I'm Black. I'm from the ghetto. I just wanted to sing.”

The Crossover and The Theft

Race, Covers, and Erasure (1950–1960)

Rock and roll's history cannot be separated from the history of American racism—in its creation, exploitation, erasure, and eventual (partial) integration.

In the 1950s, white artists routinely covered Black artists' songs with sanitized arrangements for segregated radio markets. Big Mama Thornton's 'Hound Dog' (1953) topped the R&B chart for seven weeks. She received a flat fee of $500. No royalties. Elvis's 1956 version sold 10 million copies. Thornton died penniless in 1984.

Little Richard's 'Tutti Frutti' was covered by Pat Boone, who outsold the original. LaVern Baker's 'Tweedle Dee' was covered by Georgia Gibbs using nearly the identical arrangement. Baker was so frustrated she petitioned Congress to outlaw note-for-note covers.

Yet something else was happening. At rock and roll shows, the segregated seating—often enforced by literal ropes—began to collapse. Ralph Bass, Chess Records producer: 'Then, hell, the rope would come down, and they'd all be dancing together.' Music became a space where integration happened in practice before it was achieved in law.

Barbara Weinberg Barefield, CC BY-SA 3.0

Barbara Weinberg Barefield, CC BY-SA 3.0Big Mama Thornton

Hound Dog Original

1926–1984Her 1953 'Hound Dog' topped the R&B chart for seven weeks, sold 500,000+ copies. Paid a flat fee of $500, no royalties. Died penniless in Los Angeles.

“Didn't get no money from them at all. Everybody livin' in a house but me. I'm just livin.” — 1984

Topps Gum Cards, Public Domain

Topps Gum Cards, Public DomainLittle Richard

The Architect of Rock and Roll

1932–2020Recorded 'Tutti Frutti,' 'Long Tall Sally,' 'Good Golly Miss Molly.' Self-proclaimed innovator, originator, and architect of rock and roll.

“I am the innovator. I am the originator. I am the emancipator. I am the architect of rock 'n' roll.”

Atlantic Records, Public Domain

Atlantic Records, Public DomainLaVern Baker

Rock's First Lady

1929–1997Atlantic Records star whose 'Tweedle Dee' (1954) was covered note-for-note by Georgia Gibbs. Baker petitioned Congress for copyright protection—the first artist to publicly fight back against cover theft. Rock Hall 1991.

“I was making hits while they were making copies.”

The Feedback Loop

The British Invasion Returns the Blues (1958–1966)

The British Invasion was not merely an export of American music—it was a transformation that changed American rock itself. In October 1958, Muddy Waters toured the UK. British audiences, expecting acoustic folk blues, were stunned by his electric ferocity.

Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies founded Blues Incorporated in 1961—'Britain's First Rhythm & Blues Band.' The Ealing Club became a training ground. Young musicians who would become the Rolling Stones, Cream, and Led Zeppelin cycled through.

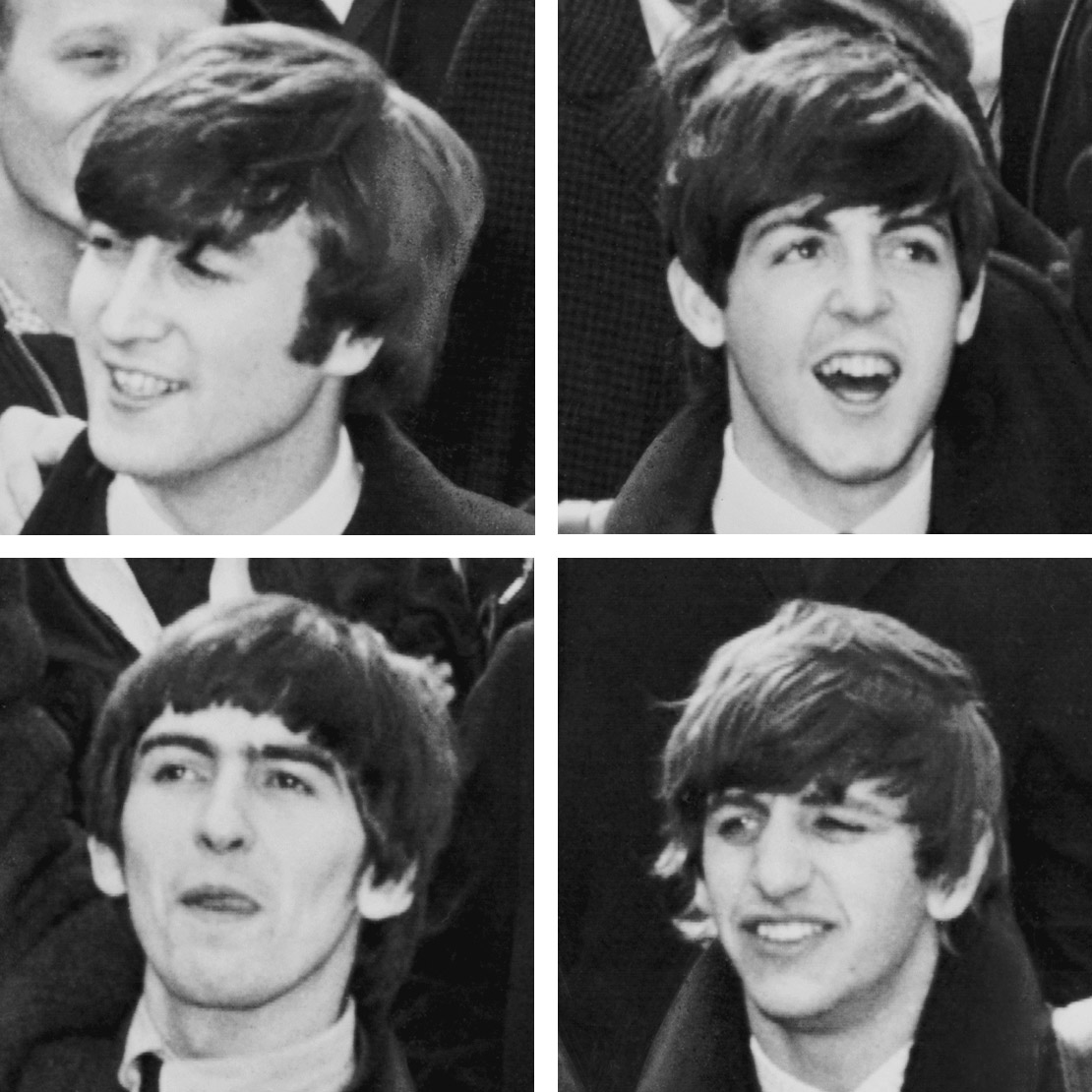

On February 9, 1964, the Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan. 73 million Americans watched. The British Invasion began. But the British bands carried a secret cargo: American blues. The Rolling Stones named themselves after a Muddy Waters song. They recorded at Chess Records, 2120 South Michigan Avenue.

White British teenagers reintroduced Black American music to white American teenagers. The feedback loop was complete—but the original creators were still being credited last.

Bernard Gotfryd, Public Domain

Bernard Gotfryd, Public DomainThe Beatles

Liverpool's Gift to the World

1960–197073 million watched their Ed Sullivan appearance (February 9, 1964). Hamburg crucible transformed raw talent into world-beaters.

“I was born in Liverpool, but I grew up in Hamburg.” — John Lennon

London Records, Public Domain

London Records, Public DomainThe Rolling Stones

Blues Devotees

1962–presentNamed after a Muddy Waters song. Recorded at Chess Records. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards reconnected over blues albums.

“We wanted to turn people on to blues. That was the whole idea.” — Keith Richards

Apple Records, Public Domain

Apple Records, Public DomainRonnie Spector

The Voice of the Wall of Sound

1943–2022Lead singer of The Ronettes. 'Be My Baby' (1963) defined Phil Spector's Wall of Sound—its opening drum beat became the most imitated in rock history. Brian Wilson pulled his car over when he first heard it. The Beatles, the Stones, Springsteen—all cite her as foundational.

“I used to tell myself, 'Ronnie, someday you're gonna be free, and you're gonna make music again.'”

Global Amplification

Rock Spreads Worldwide (1964–1980)

Rock and roll was never just American or British. Almost as soon as it had a name, it began to travel—and everywhere it landed, it adapted.

In Brazil, Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil led Tropicalia—a movement fusing psychedelic rock with Brazilian traditions. Os Mutantes became the 'house band' of the movement. But the music was too radical for Brazil's military dictatorship. In 1969, Veloso and Gil were arrested, imprisoned, and eventually exiled.

The Beatles' performances at Tokyo's Budokan in June-July 1966 triggered Japan's 'Group Sounds' explosion. In Germany, Kraftwerk, Neu!, and Tangerine Dream rejected both Anglo-American rock and conservative German culture, creating electronic rock that would influence punk, new wave, and all electronic music that followed.

Governo do Estado de São Paulo, CC BY 2.0

Governo do Estado de São Paulo, CC BY 2.0Caetano Veloso

Tropicalia Founder

b. 1942Led Tropicalia movement with Gilberto Gil, fusing psychedelia with Brazilian traditions. Arrested by military regime 1969; later exiled.

“The violent aspect of rock 'n' roll interested us more because we were seeing violence.”

The Fracturing

Genre Evolution (1968–1995)

Rock didn't stay unified. From the late 1960s, it splintered into genres—each with its own rules, heroes, and audiences. And in every genre, women were there from the beginning.

Aretha Franklin commanded soul-rock crossover with Muscle Shoals sessions. Janis Joplin brought blues intensity to rock's biggest stages. Grace Slick fronted Jefferson Airplane through psychedelia's peak. Black Sabbath emerged from Birmingham in 1968, creating heavy metal. Heart proved women could match that heaviness—Ann Wilson's vocals soaring over Nancy's hard rock guitar.

CBGB at 315 Bowery became ground zero for punk. The Ramones stripped rock to three chords. But alongside them: Patti Smith merged poetry and punk with 'Horses' (1975). Debbie Harry made Blondie a new wave powerhouse. Suzi Quatro pioneered leather-clad female rock stardom, directly inspiring Joan Jett.

On August 1, 1981, MTV launched. Pat Benatar brought rock credibility to the video age. The Go-Go's became the first all-female band writing and playing their own #1 album. Stevie Nicks became rock royalty with Fleetwood Mac. In 1991, Nirvana's 'Nevermind' broke grunge mainstream—but so did Hole, with Courtney Love's raw confessional power. Riot grrrl exploded: Kathleen Hanna and Bikini Kill named the industry's sexism explicitly. PJ Harvey proved women could dominate art rock.

Atlantic Records, Public Domain

Atlantic Records, Public DomainAretha Franklin

Queen of Soul

1942–2018The voice that demanded R-E-S-P-E-C-T. 18 Grammys, first woman inducted into Rock Hall (1987). Her Muscle Shoals sessions bridged soul and rock, her power transcending every genre boundary.

“Being the Queen is not all about singing. It has much to do with your service to people.”

Janis Joplin

Rock's First Female Superstar

1943–1970Fronted Big Brother and the Holding Company. Her raw, soulful wail broke every barrier—except the one that killed her. Dead at 27 from overdose, she remains rock's most visceral female voice.

“Don't compromise yourself. You are all you've got.”

Grace Slick

Psychedelic Voice

b. 1939Fronted Jefferson Airplane; wrote and sang 'White Rabbit' and 'Somebody to Love' (1967). The voice of San Francisco psychedelia. Unapologetically rebellious through the 1960s and beyond.

“Through the looking glass and down the rabbit hole.”

Plismo, CC BY 2.0

Plismo, CC BY 2.0The Ramones

Punk Originators

1974–1996Stripped rock to three chords and two minutes. 'Blitzkrieg Bop' (1976) became a punk anthem.

“We decided to start our own group because we were bored with everything we heard.” — Joey Ramone

Capitol Records, Public Domain

Capitol Records, Public DomainAnn & Nancy Wilson

Heart

b. 1950 / b. 1954Proved women could play hard rock at the highest level. 'Barracuda,' 'Crazy on You,' 35 million albums sold. Sisters who led a band in a man's world and never backed down.

“We had to be twice as good to be taken half as seriously.”

Beni Muck, CC BY-SA 2.0

Beni Muck, CC BY-SA 2.0Patti Smith

Punk Poet Laureate

b. 1946Merged poetry and punk with 'Horses' (1975), one of rock's most influential debuts. 'Because the Night' (1978) co-written with Springsteen. Godmother of punk, still performing.

“Jesus died for somebody's sins but not mine.”

Chrysalis Records, Public Domain

Chrysalis Records, Public DomainDebbie Harry

Blondie

b. 1945Fronted Blondie; crossed genres from punk to disco to rap. 'Heart of Glass,' 'Call Me,' 'Rapture'—the last being the first rap song to hit #1. Made new wave glamorous and dangerous.

“I wasn't a sex symbol, I was a sex object. But I used it.”

Andrew Hurley, CC BY-SA 2.0

Andrew Hurley, CC BY-SA 2.0Joan Jett

Rock's Bad Reputation

b. 1958Rejected by 23 labels; formed Blackheart Records. 'I Love Rock 'n' Roll' (1981) spent eight weeks at #1. Proved women could build their own empires.

“I don't give a damn 'bout my bad reputation.”

Warner Bros., Public Domain

Warner Bros., Public DomainStevie Nicks

Rock Royalty

b. 1948Joined Fleetwood Mac in 1975; 'Rumours' sold 40 million copies. Solo career with 'Edge of Seventeen.' First woman inducted into Rock Hall twice (with Fleetwood Mac and solo).

“I'm not just a rock star. I'm a survivor.”

Chrysalis Records, Public Domain

Chrysalis Records, Public DomainPat Benatar

Rock's Voice on MTV

b. 1953Four consecutive Grammy Awards for Best Female Rock Vocal. 'Hit Me with Your Best Shot,' 'Love Is a Battlefield.' Brought rock credibility to the video age.

“We are young, heartache to heartache we stand.”

IRS Records, Public Domain

IRS Records, Public DomainThe Go-Go's

All-Female #1

Formed 1978First all-female band to write their own songs, play their own instruments, and have a #1 album ('Beauty and the Beat,' 1981). 'We Got the Beat,' 'Our Lips Are Sealed.' Rock Hall 2021.

“We didn't set out to make history. We just wanted to make music.”

Sire Records, Public Domain

Sire Records, Public DomainChrissie Hynde

The Pretender

b. 1951Founded The Pretenders; 'Brass in Pocket' (1979). Uncompromising leadership, distinctive voice. One of rock's great frontpeople, period.

“I wasn't going to be a woman in rock. I was going to be a musician.”

DGC Records, Public Domain

DGC Records, Public DomainKurt Cobain

Grunge Martyr

1967–1994Nirvana frontman; 'Nevermind' sold 30 million copies. Suicide at 27 ended grunge's brightest voice.

“I'd rather be hated for who I am than loved for who I am not.”

Colin Mutchler, CC BY-SA 2.0

Colin Mutchler, CC BY-SA 2.0Kathleen Hanna

Riot Grrrl

b. 1968Led Bikini Kill; named the industry's sexism explicitly. 'Girls to the front!' Riot grrrl gave women a voice and a movement. Later formed Le Tigre and The Julie Ruin.

“Punk rock should mean freedom.”

DGC Records, Public Domain

DGC Records, Public DomainCourtney Love

Hole

b. 1964Fronted Hole; 'Live Through This' (1994) was raw confessional rock released the same week as Nirvana's end. Controversial, confrontational, unapologetically herself.

“I'm not a woman. I'm a force of nature.”

Kris Krug, CC BY-SA 2.0

Kris Krug, CC BY-SA 2.0PJ Harvey

Art Rock Auteur

b. 1969Only artist to win the Mercury Prize twice. From 'Rid of Me' (1993) to 'Let England Shake' (2011), an uncompromising artistic vision across 30 years. Proved women could dominate art rock on their own terms.

“I don't think about gender. I think about making the best possible work.”

The Full Chorus

Recognition at Last (1987–Present)

For decades, rock history was told with half the band missing. The women who invented the sound, who taught the moves, who wrote the songs—they were there all along. Now we hear them.

In 1987, Aretha Franklin became the first woman inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It took 45 more years to induct Sister Rosetta Tharpe—the woman who invented the rock guitar style in the 1940s. Ruth Brown fought for 20 years to get royalties from Atlantic, the label she built. Tina Turner left an abusive marriage with 36 cents, then became the highest-grossing solo touring artist of her era.

The reckoning continues. The Go-Go's entered the Rock Hall in 2021. Stevie Nicks became the first woman inducted twice. Young artists now cite Big Mama Thornton and Sister Rosetta Tharpe by name. Documentaries like 'Twenty Feet from Stardom' and 'The Go-Go's' tell the complete story.

The women profiled throughout this essay—in every chapter, in every era—are no longer footnotes. From Ma Rainey to PJ Harvey, they were the foundation. We finally know.

Iris Schneider / Los Angeles Times, CC BY 4.0

Iris Schneider / Los Angeles Times, CC BY 4.0Tina Turner

The Queen of Rock 'n' Roll

1939–2023Left an abusive marriage in 1976 with 36 cents and a Mobil gas card. Eight years later, 'Private Dancer' sold 20 million copies. At 44, she became the oldest solo female artist to top the charts. She didn't just survive—she became the undisputed Queen of Rock 'n' Roll.

“I will never give up, and I will never give in.”

Atlantic Records, Public Domain

Atlantic Records, Public DomainRuth Brown

Miss Rhythm—Justice at Last

1928–2006Her hits made Atlantic 'The House That Ruth Built.' Left the label in the 1960s with no savings; worked as a bus driver, floor scrubber. Fought for 20 years; won $20,000 in back royalties and established the Rhythm and Blues Foundation. Rock Hall 1993. Tony Award 1989.

“They called Atlantic 'The House That Ruth Built.' But Ruth wasn't getting paid. Until she fought back.”

Public Domain

Public DomainSister Rosetta Tharpe

The Godmother—Recognized

1915–1973Invented the rock guitar style in the 1940s—a decade before Chuck Berry or Elvis. Influenced every guitarist who followed. Died in 1973, largely forgotten by rock historians. Inducted into Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2018—45 years later. Her legacy is finally secure.

“All this new stuff they call Rock and Roll, why I've been playing that for years now.” — 1957

Barbara Weinberg Barefield, CC BY-SA 3.0

Barbara Weinberg Barefield, CC BY-SA 3.0Big Mama Thornton

Hound Dog Original—Remembered

1926–1984Her 1953 'Hound Dog' topped the R&B chart for seven weeks. Paid $500, no royalties. Elvis's version made him the King. She died in a Los Angeles boarding house with $10,000. Today, she's finally credited as the original—every article about 'Hound Dog' names her first.

“Didn't get no money from them at all. Everybody livin' in a house but me.” — 1984

The Invisible Architects

Producers, Engineers, and Session Musicians

Behind every rock hit, there are names you've never heard. Producers who shaped the sound. Engineers who captured it. Session musicians who played on more hits than the stars themselves.

Phil Spector created the 'Wall of Sound' at Gold Star Studios. George Martin was the 'Fifth Beatle.' The Wrecking Crew in Los Angeles played on more #1 hits than anyone can count—drummer Hal Blaine played on 40 #1 singles. Bassist Carol Kaye played on 'Good Vibrations,' 'Wichita Lineman,' and thousands more.

The Funk Brothers at Motown played on more #1 hits than the Beatles, Elvis, Rolling Stones, and Beach Boys combined—yet most died unknown and uncompensated.

George Martin

The Fifth Beatle

1926–2016Produced virtually all Beatles recordings. Arranged strings, experimented with tape effects, enabled the band's artistic evolution.

Carol Kaye

Bass Legend

b. 1935Played bass on 'Good Vibrations,' 'Wichita Lineman,' and thousands more. One of few female session musicians in a male-dominated field.

“I played on so many records, I stopped counting.”

The Living Sound

Rock's Ongoing Evolution (1986–Present)

Rock and roll was never meant to stay still. From the moment it had a name, it began to travel, to mutate, to merge with every local tradition it touched. Every decade declares rock dead; every decade it returns transformed.

In Brazil, Tropicalia's children still fuse rock with samba. In Mali and Niger, Tinariwen and Bombino play 'desert blues'—the music completing a circle back to its African roots. K-rock and J-rock thrive in Asia. Måneskin won Eurovision 2021 with raw Italian rock. In every city in the world, somewhere right now, a teenager is picking up a guitar for the first time.

The story is no longer written by critics in a few cities. Hip-hop sampled rock and took it somewhere new. Olivia Rodrigo cites Paramore who cite Blondie who cite the Ronettes. Brittany Howard, Fantastic Negrito, Yola, and Black Pumas carry the tradition forward, explicitly naming their lineage. The history is being told correctly now—not just who made the music, but who made the music possible.

Rock and roll began as a convergence—gospel, blues, country, rhythm and blues, all flowing together into something the world had never heard. It was made by Black hands and white hands, by women and men, by the poor who had nothing but a guitar and a voice. From Memphis to Liverpool to Tokyo to Lagos to São Paulo and back. Seventy years later, the noise continues. The noise that remade the world.

Sources & Further Reading

Primary Archives (.gov)

Institutional Archives

Academic Books

Documentaries

Complete bibliography with 100+ sources available in the research package.

Image Credits

All images sourced from Wikimedia Commons. Click names to view original files.

- Sister Rosetta Tharpe — Public Domain

- Louis Jordan — William P. Gottlieb, Public Domain

- T-Bone Walker — Heinrich Klaffs, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Fats Domino — Teddyyy, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Ike Turner — Heinrich Klaffs, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Alan Freed — ABC-TV, Public Domain

- Leo Fender — Fender Guitar Factory Museum, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Sam Phillips / Sun Studio — Thomas R Machnitzki, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Earl Palmer — Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Fair Use

- Cosimo Matassa — PRA, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Elvis Presley — MGM, Public Domain

- Jerry Lee Lewis — Sun Records, Public Domain

- Chuck Berry — Chess Records, Public Domain

- Muddy Waters — Chess Records, Public Domain

- Big Mama Thornton — Stephanie Wiesand, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Little Richard — CBS Television, Public Domain

- The Beatles — United Press International, Public Domain

- The Rolling Stones — Decca Records, Public Domain

- Caetano Veloso — Governo do Estado de São Paulo, CC BY 2.0

- The Ramones — Plismo, CC BY 2.0

- Nirvana / Kurt Cobain — DGC Records, Public Domain

- Joan Jett — Andrew Hurley, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Janis Joplin — Albert B. Grossman Management, Public Domain

- George Martin — EMI Records, Public Domain

- Ruth Brown — Atlantic Records, Public Domain

- Tina Turner (Ike & Tina era) — Nationaal Archief, CC0

- Tina Turner (solo era) — Iris Schneider / Los Angeles Times, CC BY 4.0

- Ma Rainey — Public Domain

- Bessie Smith — Carl Van Vechten, Public Domain

- LaVern Baker — Atlantic Records, Public Domain

- Etta James — Chess Records, Public Domain

- Wanda Jackson — Public Domain

- Aretha Franklin — Atlantic Records, Public Domain

- Grace Slick — RCA Records, Public Domain

- Ronnie Spector — Public Domain

- Heart (Ann & Nancy Wilson) — Capitol Records, Public Domain

- Patti Smith — Beni Muck, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Debbie Harry — Chris Stein, Public Domain

- Stevie Nicks — Public Domain

- Pat Benatar — Chrysalis Records, Public Domain

- The Go-Go's — IRS Records, Public Domain

- Chrissie Hynde — Sire Records, Public Domain

- Kathleen Hanna — Colin Mutchler, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Courtney Love — DGC Records, Public Domain

- PJ Harvey — Kris Krug, CC BY-SA 2.0