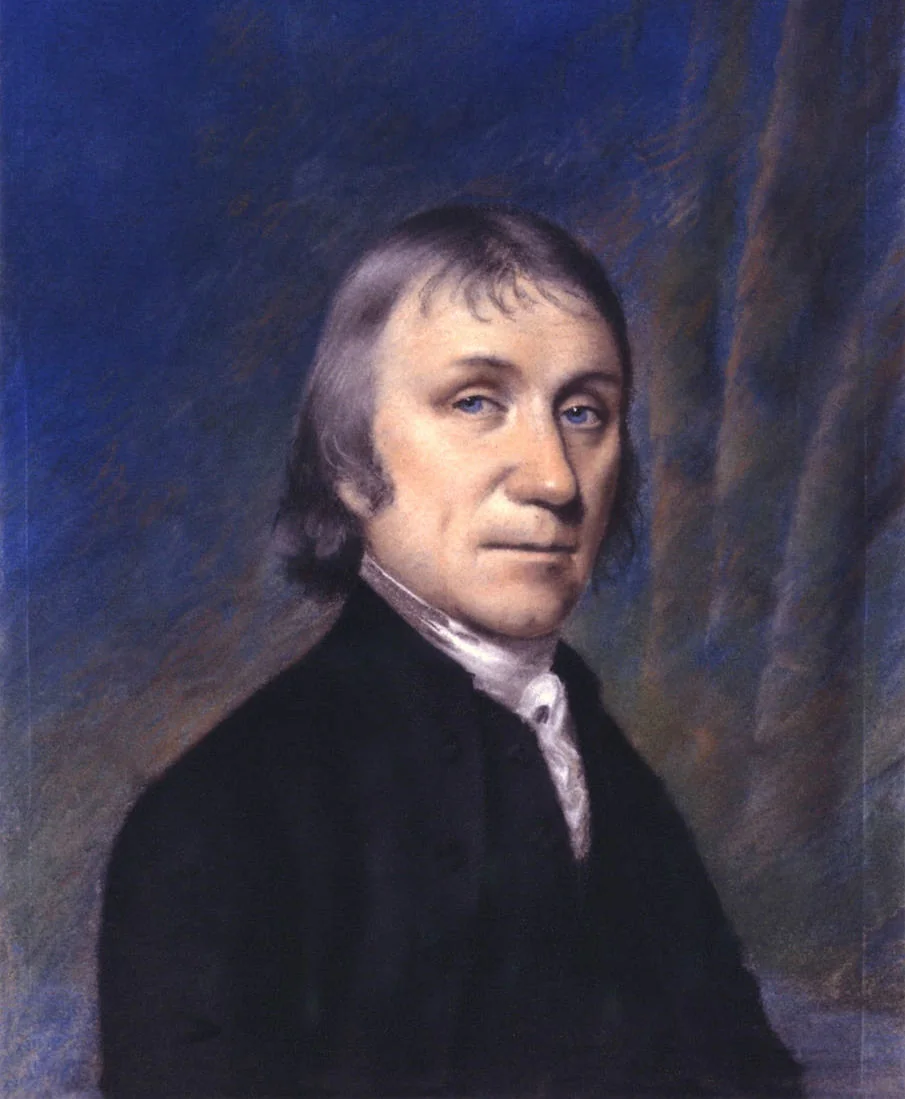

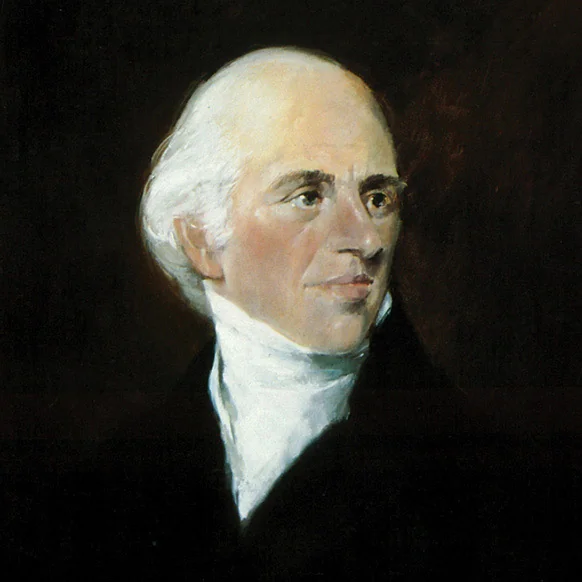

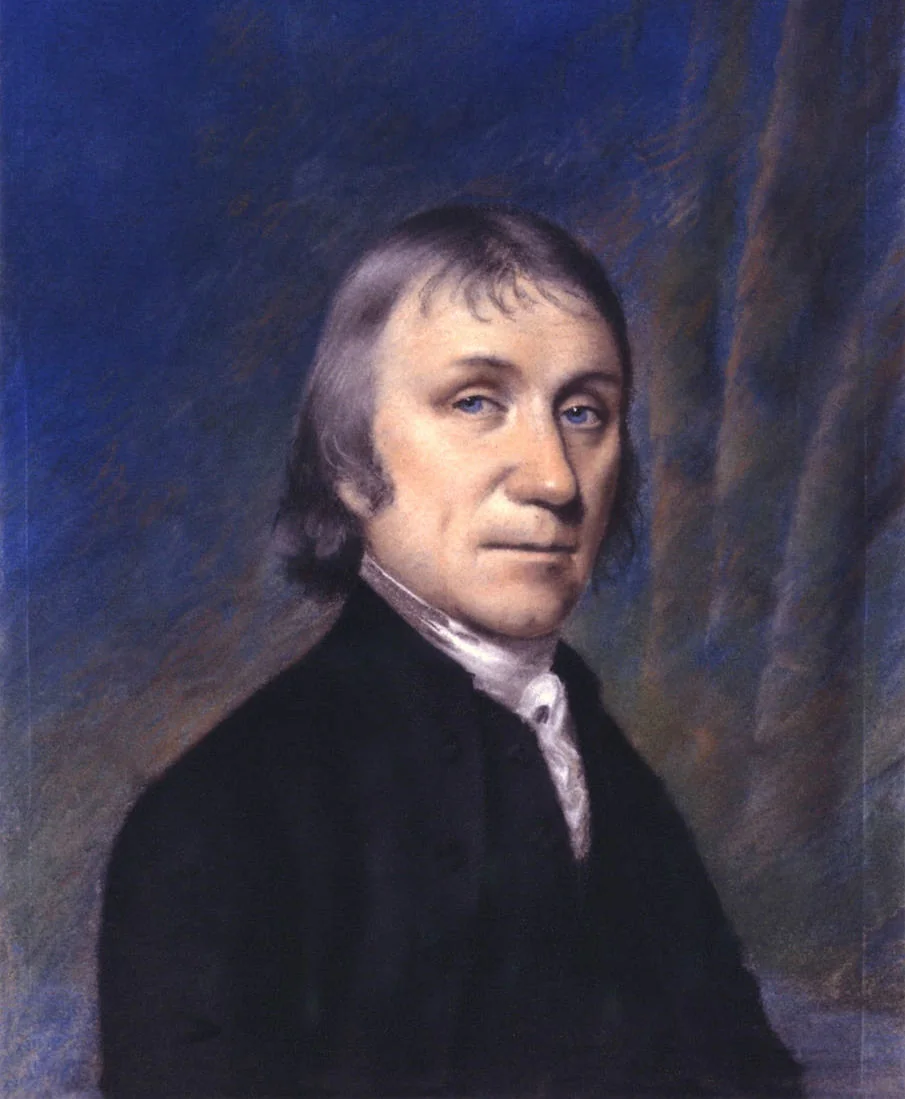

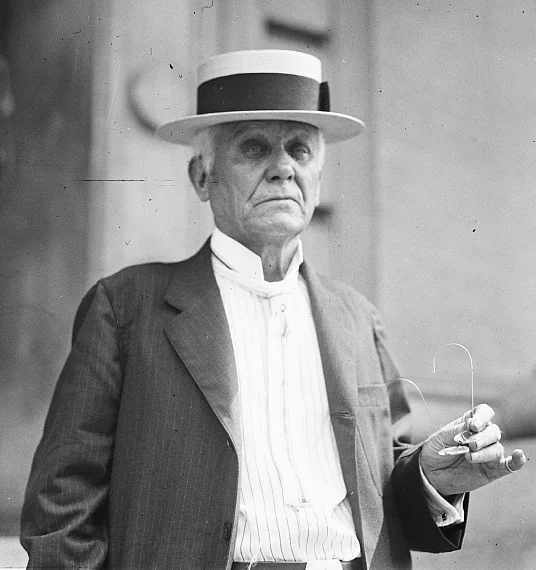

Ellen Sharples, Public Domain

Ellen Sharples, Public DomainJoseph Priestley

First to create artificial carbonated water in 1767 at a Leeds brewery. Called it his "happiest discovery."

From Scientific Discovery to Global Cultural Phenomenon

How a Leeds brewery experiment became 1.9 billion daily servings. The pharmacists, the marketers, the wars, and the 79-day mistake.

In 1767, an English clergyman and amateur scientist made a discovery that would eventually spawn a $450 billion industry. Joseph Priestley wasn't looking for refreshment—he was looking for science.

Living next to a brewery in Leeds, Priestley noticed that a layer of gas hovered over the fermenting beer vats. He suspended a bowl of water over the vat and observed that the water absorbed the gas. When he tasted it, he described "an exceedingly pleasant sparkling water, resembling Seltzer water."

Priestley published his method in 1772 ("Impregnating Water with Fixed Air") and received the Copley Medal from the Royal Society in 1773. He believed his discovery could prevent scurvy on long sea voyages.

"This is perhaps the happiest discovery I have ever made."— Joseph Priestley, on artificial carbonation

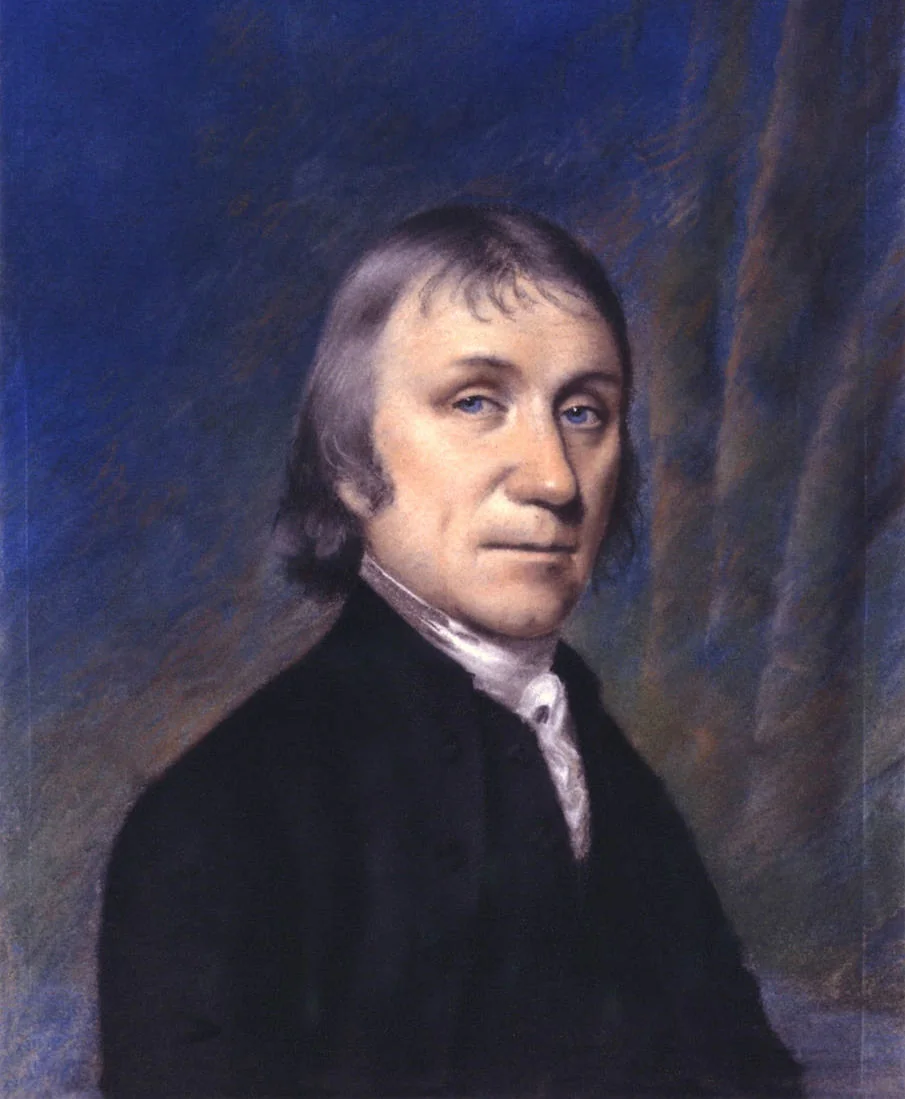

But Priestley was a scientist, not an entrepreneur. He shared his method freely and never commercialized it. Swedish chemist Torbern Bergman improved the process in 1771, but it would take 16 years for someone to see the business potential.

Johann Jacob Schweppe was a watchmaker, not a scientist. But he understood something Priestley didn't: people would pay for pleasant sparkling water.

In 1783, working in Geneva, Schweppe patented a commercial process for manufacturing carbonated water. He called his company J. Schweppe & Co.— the first soft drink company in history.

Schweppe expanded to London in 1792, establishing a factory at 141 Drury Lane. By 1831, Schweppes had received a Royal Warrant as official supplier to the British Royal Household. At the 1851 Great Exhibition, Schweppes sold over a million bottles.

The lesson was clear: scientific discoveries don't automatically become industries. It takes an entrepreneur to see commercial potential in what scientists consider mere curiosities.

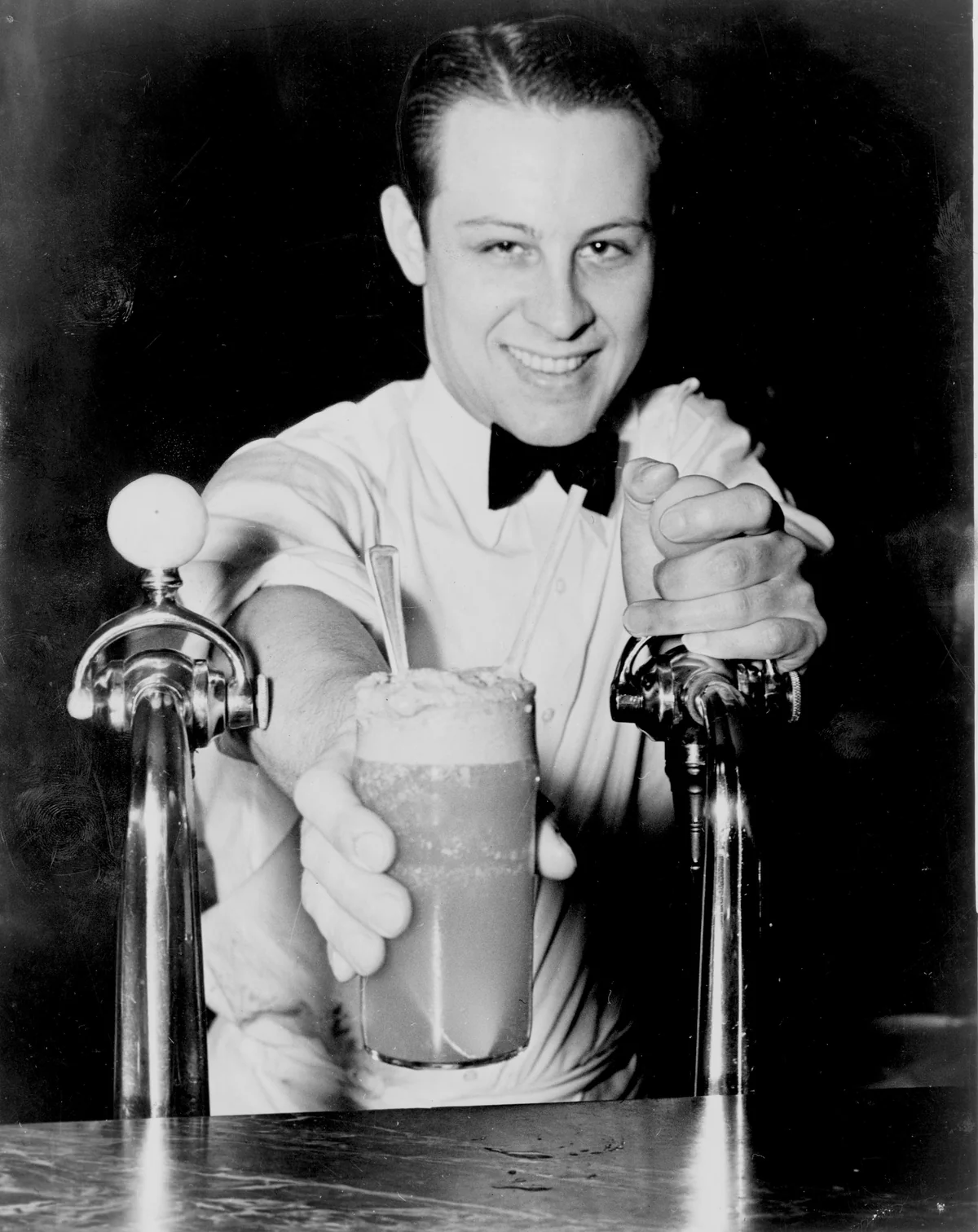

Nearly every major American soft drink was invented by a pharmacist. The soda fountain—where pharmacists dispensed medicinal carbonated waters— was the 19th century's equivalent of the tech startup garage.

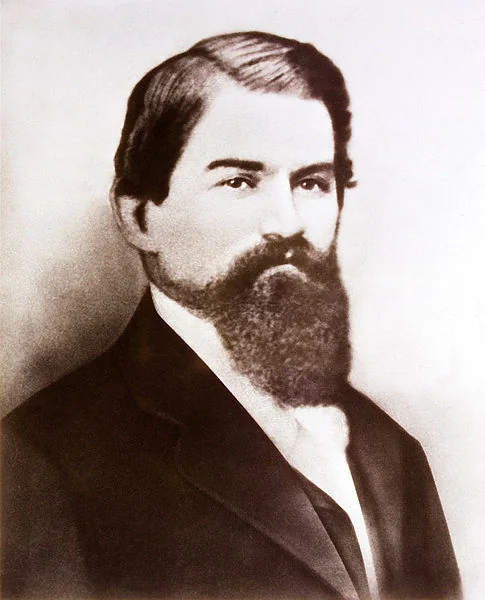

In 1885, Charles Alderton created Dr Pepper in Waco, Texas. In 1886, John Stith Pemberton invented Coca-Cola in Atlanta. In 1893, Caleb Bradham created "Brad's Drink" (later Pepsi-Cola) in New Bern, North Carolina.

These pharmacists had chemical knowledge, access to ingredients, retail locations, and customers seeking "tonics." The soft drink industry emerged from medicine, not food. Coca-Cola's original formula contained trace amounts of cocaine (from coca leaf) until 1903.

Frank Robinson, Pemberton's partner, suggested the name Coca-Cola, reasoning that "the two Cs would look well in advertising." He designed the famous Spencerian script logo that remains virtually unchanged today.

Asa Candler didn't invent a better soda. He invented modern brand marketing.

In 1891, Candler acquired Coca-Cola for $2,300—possibly history's greatest return on investment. While competitors listed ingredients, Candler sold an experience.

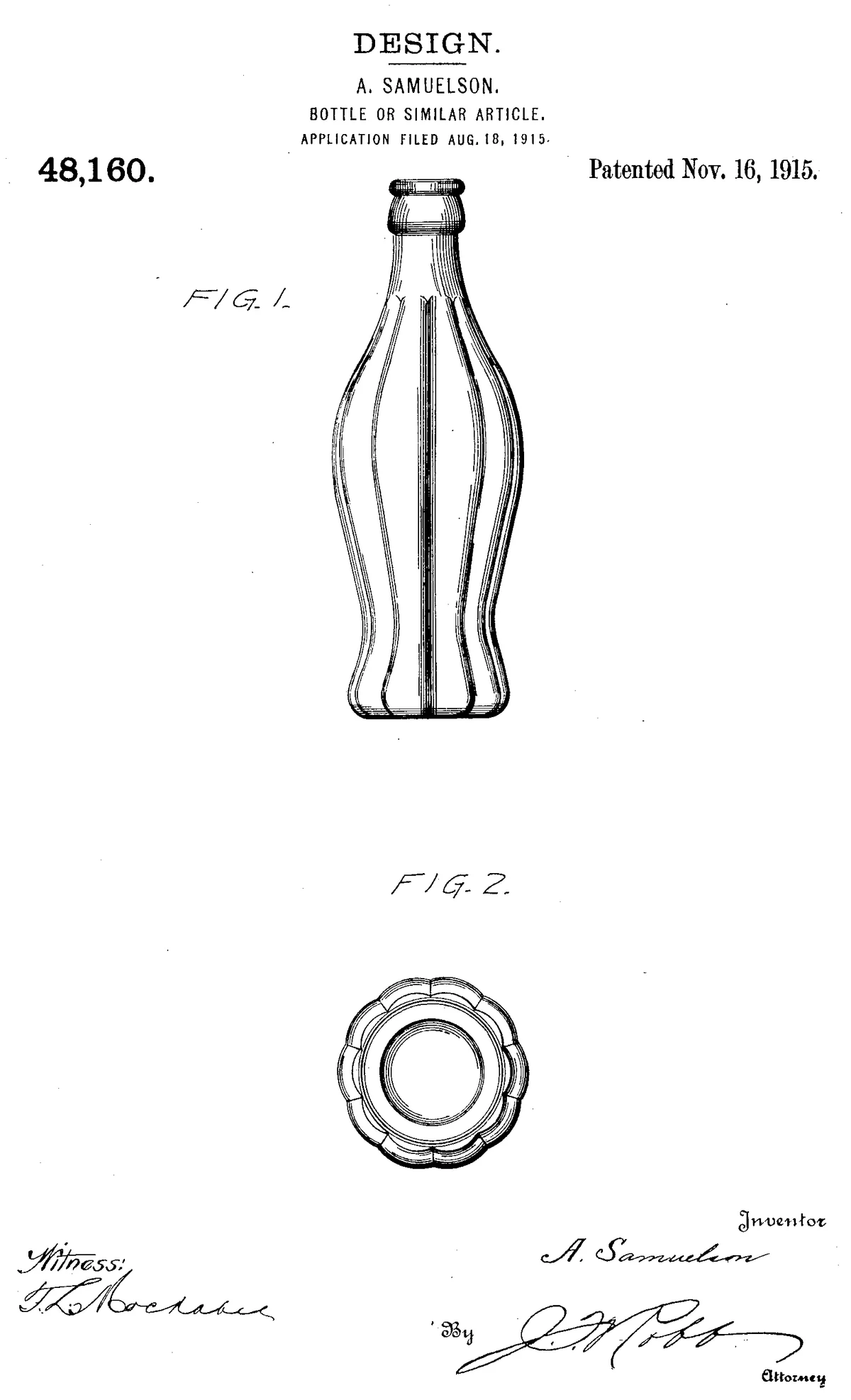

In 1915, the Root Glass Company designed the iconic contour bottle— recognizable even in the dark or when broken. Earl Dean based the design on a cocoa pod (he misheard "coca"). The "Georgia Green" color became a trademark.

The five-cent price held for over 70 years through three wars, the Great Depression, and massive inflation. By 1950, Coca-Cola owned 85% of America's 460,000 vending machines—all built for nickels only. In 1953, the company asked the U.S. Treasury to mint a 7.5-cent coin. The request was denied.

Robert Woodruff's 1941 directive would create a global empire: "Every man in uniform gets a bottle of Coca-Cola for five cents, wherever he is and whatever it costs our company."

What looked like patriotic sacrifice was brilliant strategy. Coca-Cola deployed 148 "Technical Observers" (nicknamed "Coca-Cola Colonels") to war zones. The company built 64 bottling plants worldwide at its own expense. 5 billion bottles reached American troops during the war.

Eisenhower's top-secret telegram ordered 3 million bottles for the North Africa invasion. By 1968, 50% of Coca-Cola's profits came from foreign operations.

The wartime plants became post-war infrastructure for global expansion. Coca-Cola became synonymous with American identity—both its promise and its imperialism. The term "Coca-Colonization" emerged to describe American cultural expansion.

"Coca-Cola was not simply a tasty beverage, but a symbol of American abundance and freedom."— Mark Pendergrast, "For God, Country and Coca-Cola"

Between 1975 and 1990, two companies waged the most intense marketing battle in commercial history. The weapon: perception. The battlefield: your mind.

"We're disarming the Soviet Union faster than you are."— Donald Kendall to Brent Scowcroft, after trading Pepsi for 17 Soviet submarines

What began with one man and one brewery now serves 1.9 billion drinks daily.

The soft drink industry today is worth between $450 and $630 billion globally. Coca-Cola products are sold in over 200 countries—only North Korea and Cuba lack official distribution. The brand is recognized by 94% of the world's population.

The industry has faced new challenges: health concerns over sugar consumption, environmental criticism of plastic bottles, and competition from energy drinks and bottled water. But the fundamental appeal remains: flavored carbonated water, just as Priestley discovered in 1767.

Key moments in carbonated history

What began with Priestley's brewery experiment now constitutes one of the largest consumer goods industries on Earth.

Eleven figures who transformed a scientific curiosity into a global phenomenon.

Ellen Sharples, Public Domain

Ellen Sharples, Public DomainFirst to create artificial carbonated water in 1767 at a Leeds brewery. Called it his "happiest discovery."

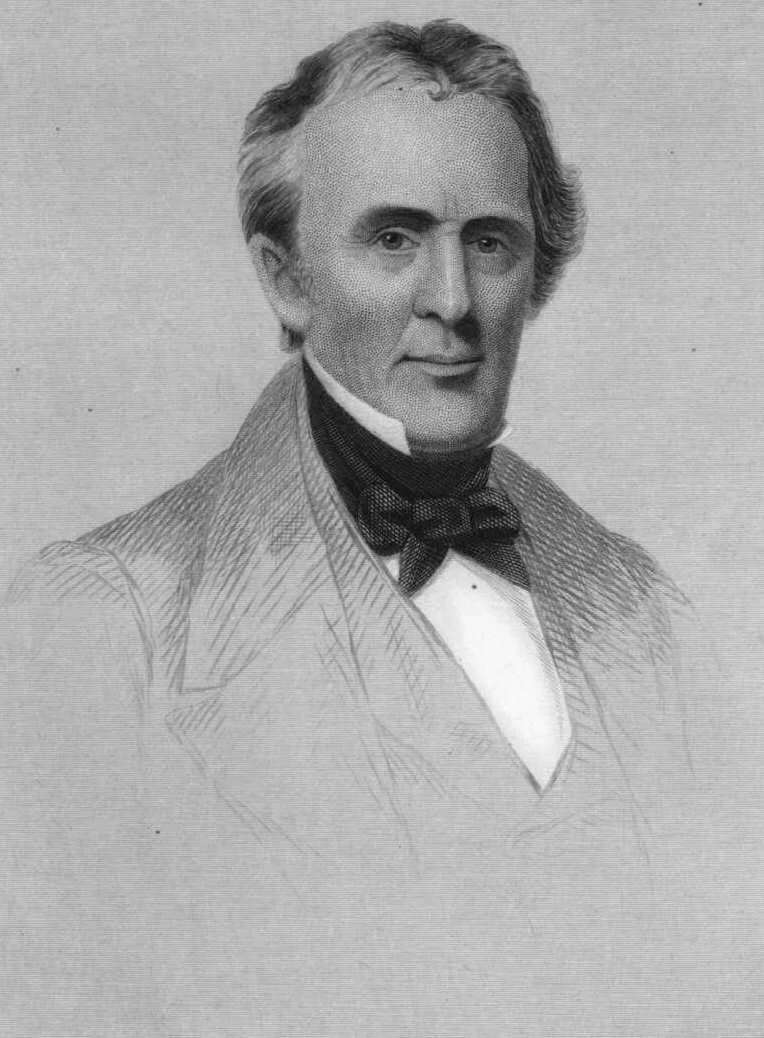

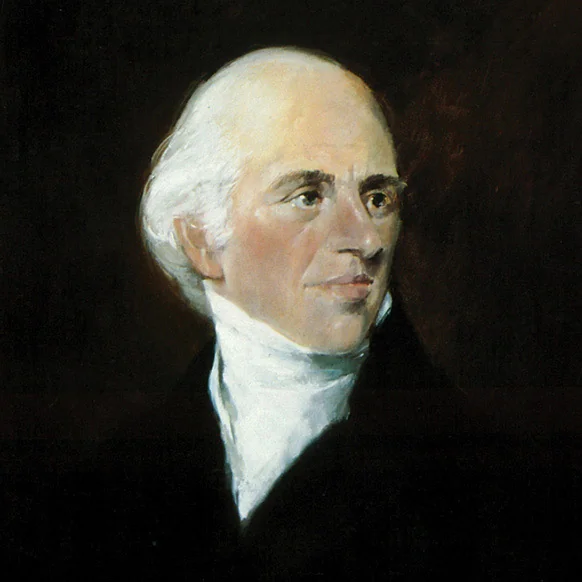

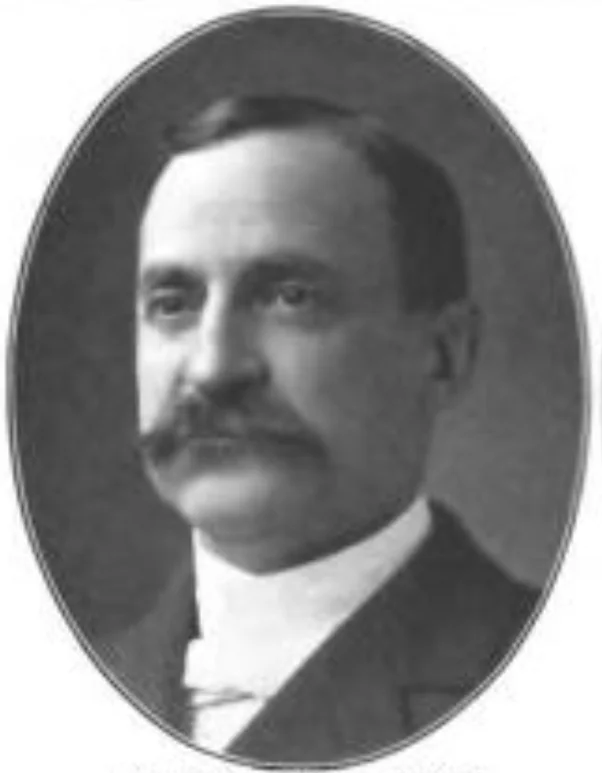

Public Domain (1783)

Public Domain (1783)German-Swiss watchmaker who commercialized carbonated water in Geneva (1783) and London (1792).

Public Domain

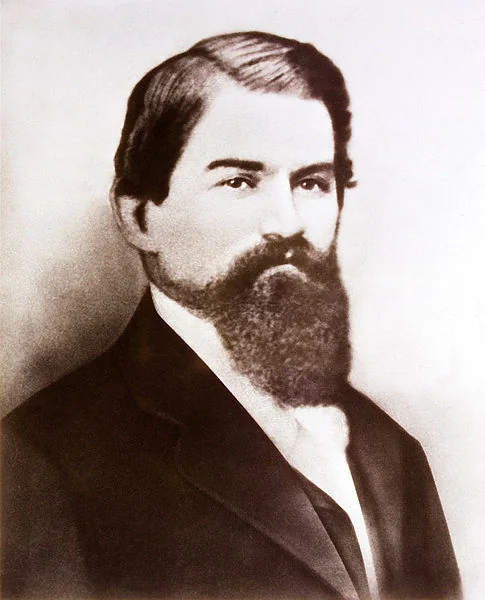

Public DomainAtlanta pharmacist who created Coca-Cola on May 8, 1886. Civil War veteran with morphine addiction.

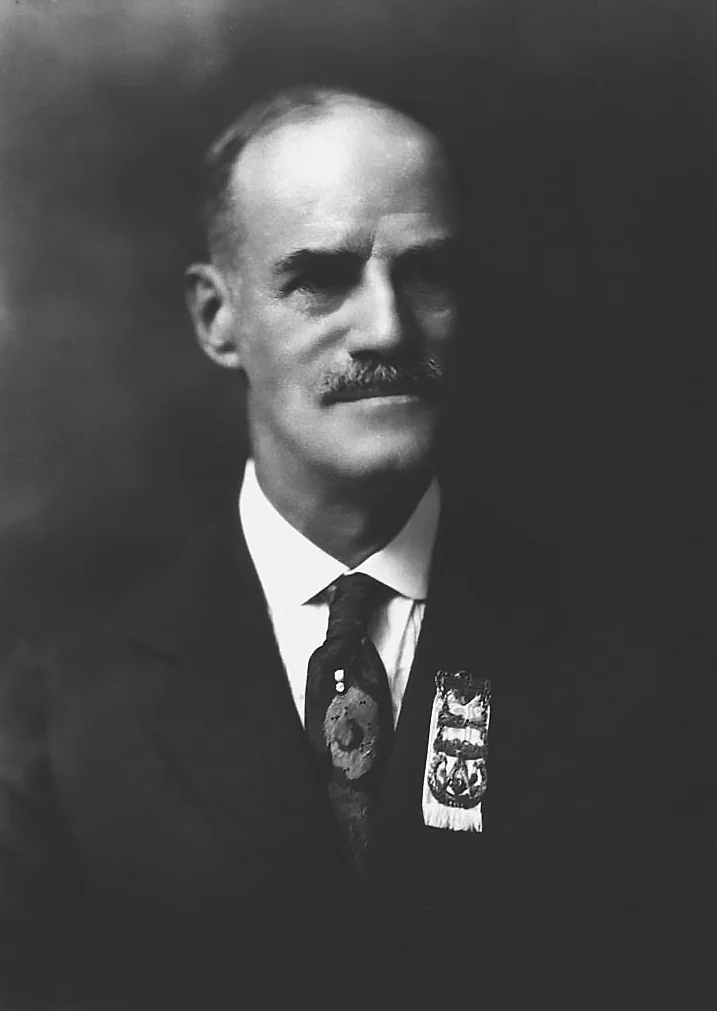

Harris & Ewing, Library of Congress

Harris & Ewing, Library of CongressBought Coca-Cola for $2,300 and invented modern brand marketing. Built a $25 million empire.

Public Domain

Public DomainNorth Carolina pharmacist who created "Brad's Drink" in 1893, renamed Pepsi-Cola in 1898.

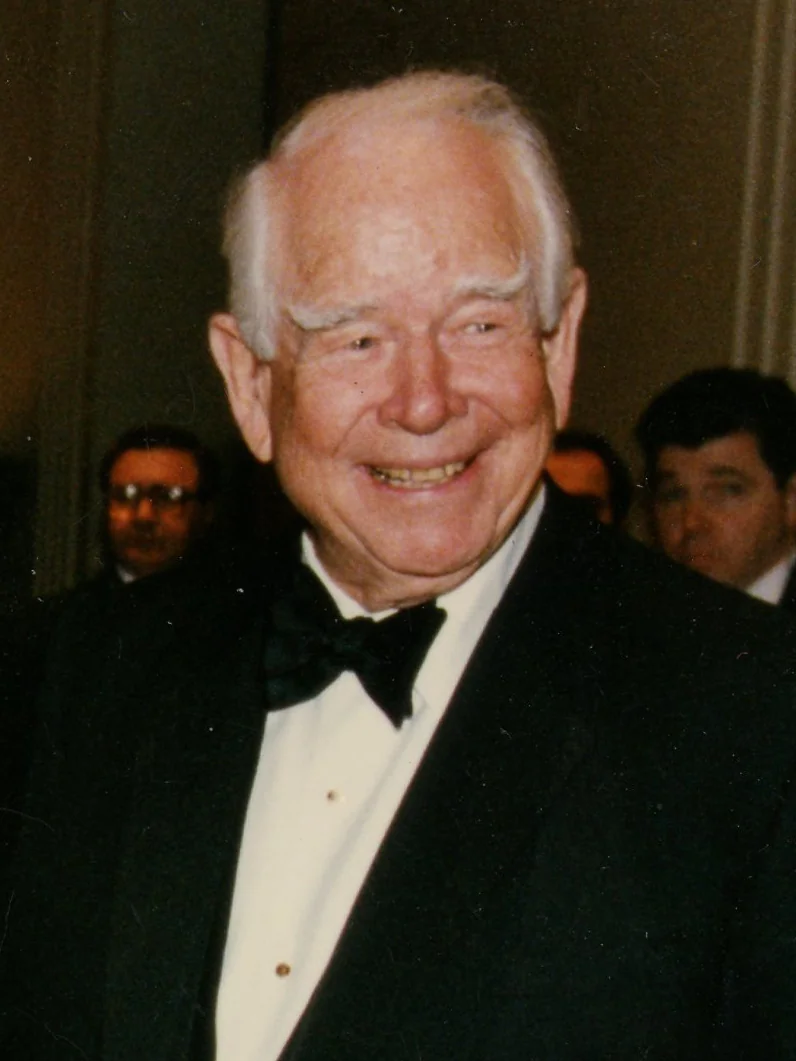

Joseph Janney Steinmetz, State Archives of Florida

Joseph Janney Steinmetz, State Archives of FloridaLed Coca-Cola's WWII expansion: 64 bottling plants, 5 billion bottles to troops.

Moses King, Public Domain

Moses King, Public DomainPhiladelphia pharmacist who created Hires Root Beer (1876) and pioneered national advertising.

Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsWaco, Texas pharmacist who created Dr Pepper in 1885—America's oldest major soft drink brand.

Vigo County Historical Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Vigo County Historical Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0Designed the iconic Coca-Cola contour bottle (1915) that became recognizable even in the dark.

Cuban-born CEO who launched New Coke (1985). Called it "smoother, rounder, yet bolder."

Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsGot Pepsi into Khrushchev's hand (1959). Later traded cola for Soviet submarines.

Market statistics sourced from Statista, Coca-Cola Company investor reports, and industry analysis (2024). Historical data verified through multiple academic sources.