Somewhere in the American South. Sometime after 1865.

The Blues

America's Haunted Foundation

A Documentary Visual History

A Note Bent Against the World

A single bent note hangs in the air. This is the blues: not a genre, but a feeling. A way of bending pitch that came from somewhere, from someone, from conditions so specific they cannot be separated from the music.

The blues is not “old.” It is not “primitive.” It emerged in the decades after emancipation, when four million freed people found themselves with nothing—no land, no capital, no legal protection—in a South determined to re-enslave them through other means.

The blues was their report, their resistance, their refusal.

“The blues are the roots and the other musics are the fruits.”— Willie Dixon

This is a story about America. Every note of jazz, rock, R&B, soul, and hip-hop bends because the blues bent first. This is where it started.

Before the Blues Had a Name

African Roots and the Pre-Conditions (1619-1890s)

The blues synthesized several distinct African American musical traditions that developed during and after enslavement.

African Elements: Bent notes (microtonality), call-and-response patterns, polyrhythmic structures, the emphasis on rhythm as carrier of meaning.

Work Songs and Field Hollers: Created to “lighten the load” of forced labor, work songs used rhythm to coordinate movement. Field hollers were solo vocal expressions—one person crying out across a cotton field—that anticipated blues' personal, emotional directness.

Spirituals: Religious music that encoded double meanings—songs about crossing Jordan meant crossing to freedom.

The blues emerged gradually between approximately 1870 and 1900, during the transition from slavery to sharecropping. No single “inventor” or birthplace can be definitively identified because blues existed as folk practice for decades before anyone documented it.

The South After Emancipation

Labor, Conditions, and the Birth of the Blues (1865-1920)

The blues emerged directly from post-emancipation economic oppression. Freed people had no land, capital, or tools. Sharecropping trapped them in perpetual debt; convict leasing re-enslaved them through the criminal justice system.

The Sharecropping Cycle: Landowners offered land use in exchange for crop share (typically 50% or more). Sharecroppers were forced to buy supplies on credit from plantation stores at inflated prices. Accounting manipulation ensured perpetual debt. Laws tied indebted workers to land.

Dockery Plantation exemplifies how labor conditions created blues. Founded in 1895, this 10,000-acre operation became “birthplace of the blues.” Workers paid in plantation scrip gathered Saturday evenings at the commissary. Musicians could earn $250 cash in one night versus 50 cents per day in fields.

Music became economic resistance.

W.C. Handy

W.C. Handy did not invent the blues—he codified and published an existing tradition for commercial consumption.

In 1903, at a train station in Tutwiler, Mississippi, he heard a man playing guitar with a knife, sliding it across the strings. This encounter changed American music.

His "Memphis Blues" (1912) and "St. Louis Blues" (1914) became the first commercially successful blues compositions.

“The primitive Southern Negro, as he sang, was sure to bear down on the third and seventh tone of the scale, slurring between major and minor.”— W.C. Handy

Regions, Roads, and Styles

Delta, Piedmont, Texas Blues (1900s-1940s)

While no single birthplace exists, distinct regional styles developed.

Mississippi Delta Blues

Raw, intensely emotional vocals. Slide (bottleneck) guitar technique. Modal, drone-based harmonic approach. Rhythmic flexibility; solo performance tradition.

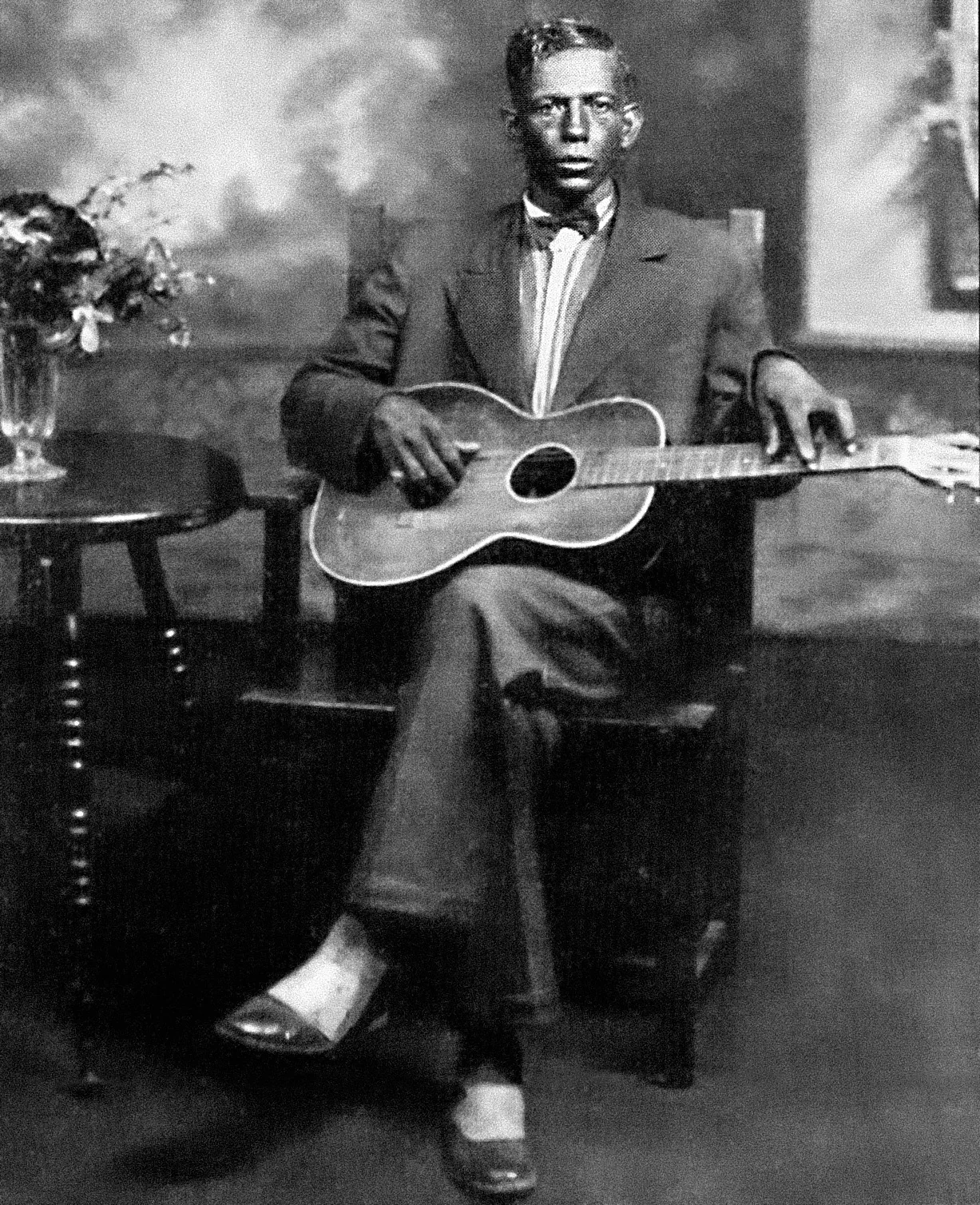

Charley Patton

Charley Patton lived and worked on Dockery Plantation from 1897, where he learned from Henry Sloan—the earliest documented Delta blues influence.

Known for his showmanship, he played guitar behind his head and between his legs—decades before Hendrix.

His voice reportedly carried 500 yards without amplification. He mentored Son House, Howlin' Wolf, and Robert Johnson.

“Pony Blues”— Added to National Recording Registry, 2006

Texas Blues

Texas blues developed its own distinctive character, shaped by the state's vast geography and diverse musical influences. Unlike the claustrophobic intensity of Delta blues, Texas blues featured cleaner, more melodic guitar work with sophisticated single-note runs influenced by jazz. The chord progressions were more varied, and the rhythms often incorporated elements of country and western swing.

Blind Lemon Jefferson, recording from 1926 to 1929, became the first major male blues star and sold millions of records. Lead Belly (Huddie Ledbetter) brought Texas blues to broader audiences after his discovery by the Lomaxes. Lightnin' Hopkins later carried the tradition into the electric era.

Piedmont Blues

Ragtime-influenced fingerpicking. Alternating bass pattern (like stride piano). Lighter, more buoyant feel than Delta. Geographic base: Eastern seaboard from Georgia to Virginia.

The railroad was crucial: lines like the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley (the “Yellow Dog”) connected isolated communities, spreading musical ideas and musicians themselves.

Instruments as Evidence

Guitar, Harmonica, Voice, and the Technologies of Blues

Blues instruments were not neutral choices. They were shaped by economics, portability, and the specific needs of Black musicians in the Jim Crow South.

The Guitar: Portable, relatively affordable, capable of accompanying voice. The slide technique—using a bottleneck, knife, or metal tube to create microtonal bends—may connect to African single-string instruments.

The Harmonica: Cheap, pocketable, indestructible. Could be played while working. Its ability to bend notes matched the blues aesthetic perfectly.

The Voice: The most fundamental instrument. Field hollers, moans, and melismatic singing connected African vocal traditions to blues expression. The human voice bending notes predates instrumental blues.

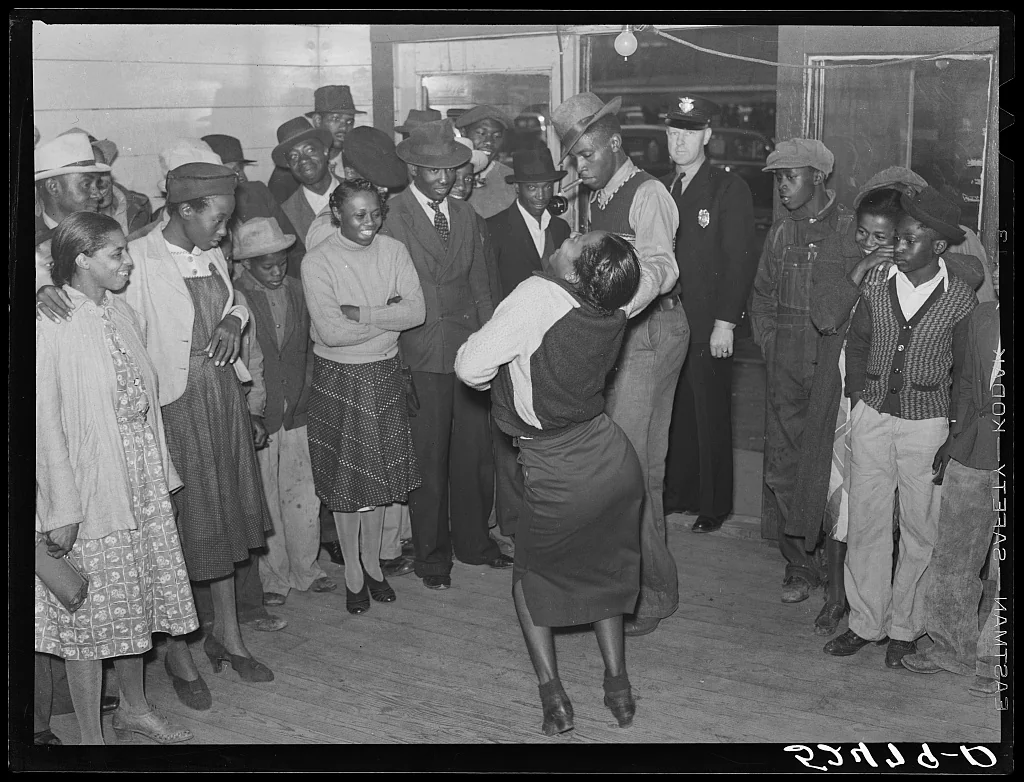

Juke Joints, Medicine Shows, and the Blues Economy

Where Blues Was Performed (1890s-1940s)

Before records, blues lived in specific places. Understanding those spaces reveals the culture's social function.

The Juke Joint: Informal drinking and dancing establishments in rural Black communities. The name may derive from Gullah “joog” (rowdy). These were spaces of release from week-long labor, of community gathering, of courtship and conflict.

Medicine Shows: Traveling spectacles that sold patent medicines using music as the draw. Ma Rainey began performing on the tent show circuit as a teenager.

Vaudeville and TOBA: The Theater Owners Booking Association (“Tough On Black Artists”) provided a circuit of Black theaters. The pay was exploitative, but it built audiences and careers.

The Recording Industry and Race Records

Documentation and Exploitation (1920-1945)

On August 10, 1920, Mamie Smith recorded “Crazy Blues” for Okeh Records. It sold 75,000 copies in its first month, over 1 million in its first year. The race records industry was born.

Industry Growth: An estimated 15,000 race record titles were released in the 1920s-1930s. Peak sales reached $100 million in 1927. The Depression collapsed sales to $6 million by 1933.

Systematic Exploitation: Artists were paid flat session fees ($25-100), with no royalties. Copyright was routinely assigned to producers or labels. Illiterate artists signed away rights unknowingly.

“Made Columbia millions of dollars but was never paid royalties.” (On Bessie Smith)

“That song sold over 2 million records. I got one check for $500 and never saw another.”— Big Mama Thornton (On 'Hound Dog')

Classic Blues and the Blues Queens

Women at the Center (1920-1935)

Women did not merely participate in blues—they dominated its commercial era. This chapter is not a sidebar; it corrects the historical record.

The Classic Blues Era (1920-1930): First blues recordings were by women (Mamie Smith). Women sold the most records (Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey). Women were the highest-paid artists. Men entered recording later, as “country” or “down-home” blues.

Ma Rainey

Gertrude "Ma" Rainey began performing as a teenager on the tent show circuit.

She recorded nearly 100 songs for Paramount Records between 1923 and 1928.

Known for dramatic stage presence, gold teeth, and sequined gowns, she mentored Bessie Smith and shaped the classic blues era.

“She claimed she "created the term 'blues'" when asked what kind of song she was singing.”

Bessie Smith

Orphaned young, Bessie Smith survived by street performing before meeting Ma Rainey around 1912.

She became the most popular female blues singer of the 1930s and Columbia Records' highest-paid Black artist.

Her "Down-Hearted Blues" (1923) sold 780,000 copies in six months. She died in a car accident near Clarksdale, Mississippi.

“I ain't good-lookin', but I'm somebody's angel child.”— Bessie Smith

“Working-class, African-American sensibility quite different from the 'uplift the race' gentility of their middle-class peers.”— Angela Davis (Blues Legacies and Black Feminism)

Myth, Legend, and the Archive

The Crossroads Debunking and What We Cannot Know

The crossroads legend is the blues' most famous story—and it's wrong.

The Robert Johnson Crossroads Myth: According to legend, Johnson sold his soul to the devil at a crossroads at midnight in exchange for supernatural guitar ability.

The Evidence: No documentation exists of Johnson making this claim himself. The legend originated from stories about Tommy Johnson(different person, no relation). The stories were conflated over time due to the shared surname.

Robert Johnson

Robert Johnson recorded only 29 songs in two sessions (1936-1937), yet became the most mythologized figure in blues history.

The crossroads legend—that he sold his soul to the devil—originated from stories about Tommy Johnson (no relation).

He studied Charley Patton and Son House carefully. His 1961 compilation sparked the blues revival.

“I went to the crossroads, fell down on my knees...”— "Cross Road Blues"—a song about travel and desperation, not devil worship

The “haunted, primitive” artist image was constructed by white promoters and archivists. Johnson was actually an ambitious young professional who studied other musicians carefully.

The music was remarkable enough without devils.

The Great Migration and the City

Blues Travels North (1916-1970)

Between 1916 and 1970, approximately 6 million African Americans relocated from the rural South to cities in the North and West. The blues migrated with them.

The Chicago Defender's Role: This African American newspaper actively promoted migration. Distributed via Pullman porters throughout the South, it publicized economic opportunities and documented Southern violence.

The Mississippi-to-Chicago Pipeline: The Illinois Central Railroad ran directly from the Delta to Chicago. Musicians could board in Clarksdale and step off on Maxwell Street.

Muddy Waters

McKinley Morganfield grew up on Stovall Plantation near Clarksdale, where Alan Lomax recorded him for the Library of Congress in 1941.

He moved to Chicago in 1943 and bought his first electric guitar in 1944.

At Chess Records, his band included Little Walter, Jimmy Rogers, and Willie Dixon. The Rolling Stones named themselves after his song.

“When I went into the clubs, the first thing I wanted was an amplifier. Couldn't nobody hear you with an acoustic.”— Muddy Waters

Electricity and the Chicago Crucible

The Amplified Blues (1945-1970)

The Chicago blues was Delta blues electrified—not just in sound but in intensity, volume, and urban energy.

“When I went into the clubs, the first thing I wanted was an amplifier. Couldn't nobody hear you with an acoustic.”— Muddy Waters

Chess Records: Founded by Leonard and Phil Chess (Polish Jewish immigrants) in 1950, Chess Records became the epicenter of Chicago blues. At 2120 S. Michigan Avenue, they recorded Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Little Walter, and Willie Dixon.

Howlin' Wolf

Chester Arthur Burnett stood 6'3" and weighed nearly 300 pounds.

He learned guitar from Charley Patton and harmonica from Sonny Boy Williamson II.

Key songs include "Smokestack Lightnin'," "Spoonful," "Killing Floor," and "Back Door Man."

“I couldn't do no yodelin', so I turned to howlin'. And it's done me just fine.”— Howlin' Wolf

Willie Dixon

Willie Dixon was staff songwriter and producer at Chess Records from 1950-1965.

He wrote over 500 songs including "Hoochie Coochie Man," "I Just Want to Make Love to You," and "Spoonful."

He founded Blues Heaven Foundation to help exploited artists recover royalties.

“The blues are the roots and the other musics are the fruits.”— Willie Dixon

Crossovers, Hybrids, and Industry Rebranding

Blues Becomes Rock, R&B, Soul (1950s-1970s)

By the late 1950s, the blues had become the foundation for virtually all American popular music—but the name “blues” was being eclipsed.

Rhythm and Blues (R&B): The term replaced “race music” in 1949.

Rock and Roll: “What they call Rock and Roll I've been playing in New Orleans for years,” said Fats Domino. Early rock hits were R&B songs rebranded.

The irony: as these genres exploded commercially, the artists who created the blues often remained impoverished while their styles generated billions.

B.B. King

Riley B. King was raised in the Mississippi Delta, cousin of Bukka White.

He became a DJ at WDIA in Memphis, nicknamed "Blues Boy"—shortened to B.B.

"The Thrill Is Gone" (1969) became his signature song. He won 15 Grammy Awards and the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

“The blues are three L's—living, loving, and hopefully laughing.”— B.B. King

Global Blues and the British Invasion

Translation Without Permission (1958-Present)

The blues didn't ask permission to travel. It went where records went, where migrants went, where radio signals reached.

The British Blues Boom: American race records exported to UK. British collectors discovered prewar blues. Young British musicians—Clapton, Rolling Stones, John Mayall—emulated American blues. Then British bands reintroduced blues to white American audiences.

The Irony: The Rolling Stones, named after a Muddy Waters song, recorded at Chess Records in 1964. This was less “discovery” than return to sender.

“The most important blues musician who ever lived.”— Eric Clapton (On Robert Johnson)

The Blues Isn't Old—It's Persistent

The blues is not a museum piece. It is not “roots music” in the sense of something that stopped growing.

Every bent note in contemporary music—in hip-hop samples, in rock guitar solos, in R&B melisma—carries the DNA of the blues. The conditions that created the blues—economic oppression, racial inequality, the need to express what cannot otherwise be said—have not disappeared.

The blues persists because it was never just entertainment. It was testimony. And testimony is always needed.

“The blues has become the basis for nearly every form of American popular music over the past 100 years: jazz, R&B, rock, hip-hop.” (Library of Congress)

What began on Dockery Plantation, in juke joints lit by kerosene, in tent shows crossing the South, became the foundation of global popular music.

The note still bends. The blues isn't old—it's persistent.

A Note on Sources

This essay acknowledges the following limitations in the historical record:

- Pre-recording era gaps: Documentation is sparse before 1920; oral histories were often collected decades after events occurred.

- Power dynamics in documentation: Most early documentation was by white collectors with varying ethical practices.

- Birth dates: Many early artists have disputed or estimated birth years, indicated by “c.” (circa) where appropriate.

- Economic records: Financial exploitation is documented through patterns and specific examples; exact figures are often estimated.

- Attribution of “firsts”: Multiple competing claims exist for various firsts; this essay uses qualified language.

- The crossroads legend: Explicitly documented as folklore, not history.