R&B

The Heartbeat That Taught Pop to Feel

Before the Name

What Race Records Hid and Revealed (1920–1948)

Before there was 'rhythm and blues,' there were 'race records'—a classification that segregated Black popular music from 1920 onward. The term, first used by Okeh Records executive Ralph Peer in 1920, was simultaneously honest about the market's racism and a commercial strategy that created the first recorded documentation of African American musical innovation. By 1942, the 'Harlem Hit Parade' chart at Billboard tracked this music, but the name remained tethered to segregation.

In juke joints and roadhouses across the American South, a technological revolution was underway. T-Bone Walker's amplified guitar work starting in 1942 proved that a single instrument could compete with a horn section. Jump blues bands like Louis Jordan and His Tympany Five merged swing with blues feeling, scoring crossover hits that reached both Black and white audiences. Big bands gave way to smaller combos—fewer musicians meant lower costs, louder amplification meant bigger impact.

By 1948, the infrastructure was emerging: independent labels like Savoy (Newark), King (Cincinnati), and Specialty (Los Angeles) competed for Black talent that major labels ignored. Radio stations programming for Black audiences—WDIA in Memphis became the first all-Black-format station in 1948—created regional markets. The music was already evolving when a Billboard reporter decided to give it a new name. What followed would reshape American popular music—and teach pop how to feel.

The Classification

Jerry Wexler and the Birth of a Genre (June 1949)

“In my capacity as a Billboard reporter I was also responsible for a minor semantic and, as it turned out, musical revolution.”

— Jerry Wexler

In June 1949, Jerry Wexler—a 32-year-old reporter at Billboard magazine—proposed replacing 'race records' with 'rhythm and blues.' The change appeared in Billboard's June 25, 1949 issue, though Wexler had been using the term in articles since 1947. The renaming was partly humanitarian (the old term was offensive to the growing postwar civil rights consciousness) and partly commercial (advertisers preferred less racially charged terminology). But the consequences extended far beyond semantics.

The classification created a chart—the Hot R&B Singles chart that would track Black popular music for the next five decades. The chart created radio formats, as stations programmed specifically to reach the audiences the chart measured. Radio formats created record-buying audiences. And suddenly, Black popular music had infrastructure: distribution networks, promotional systems, and sales tracking that, however flawed and exploitative, was functional enough to build careers and companies.

Atlantic Records was positioned perfectly. Founded in 1947 by Ahmet Ertegun and Herb Abramson with $10,000 (Ertegun's inheritance from his father, the Turkish ambassador), the label focused on jazz until Ruth Brown's signing in 1949 changed everything. Her consecutive hits—'So Long' (1949), 'Teardrops from My Eyes' (#1 R&B, 1950), 'Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean' (#1 R&B, 1953)—generated the capital that allowed Atlantic to sign Ray Charles in 1952. By decade's end, Atlantic would rank among the most successful independent labels in America.

The naming wasn't just semantic. It was economic architecture—a framework that determined who got played, who got paid, and who got remembered. A category became a culture, for better and for worse.

Jerry Wexler

The Name-Giver

Coined 'rhythm and blues' in Billboard's June 1949 issue. Later became a partner at Atlantic Records and produced Aretha Franklin's legendary sessions at Muscle Shoals. His classification created the infrastructure for R&B as an industry.

caviera, CC BY 2.0

Ruth Brown

Miss Rhythm

Built Atlantic Records with consecutive hits (1949–1960). Later co-founded the Rhythm and Blues Foundation to recover unpaid royalties—not just for herself, but for dozens of artists exploited by the industry she helped build.

“That's Atlantic Records—the house that Ruth Brown built.”

New Orleans Crucible

J&M Recording Studio and the Rolling Piano (1945–1960)

“Responsible for virtually every New Orleans R&B record that made the charts.”

— Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, on Cosimo Matassa

New Orleans was R&B's first capital, and it earned that title in a room just 15 by 16 feet. At J&M Recording Studio on North Rampart Street, teenage engineer Cosimo Matassa—only 18 when he opened the studio in 1945—captured a sound that would define the genre: rolling piano triplets borrowed from Professor Longhair, second-line rhythms inherited from brass band funerals, and warm vocal tones that reflected the city's Caribbean and French influences. Between 1947 and 1960, virtually every New Orleans R&B hit was recorded in that cramped space.

Fats Domino's 'The Fat Man,' recorded on December 10, 1949, became one of the first R&B records to sell a million copies. Its success established a pattern: Domino's rolling piano style, producer Dave Bartholomew's tight arrangements, and Matassa's intimate engineering created 35 consecutive Top 40 hits between 1950 and 1963. Domino would sell 65 million records—more than any 1950s artist except Elvis Presley, who openly acknowledged his debt to the New Orleans sound.

The city produced a remarkable concentration of talent. Little Richard improvised 'Tutti Frutti' at the Dew Drop Inn before recording it at J&M in September 1955, launching rock and roll's most flamboyant career. Lloyd Price's 'Lawdy Miss Clawdy' (1952) sold a million copies with a young Fats Domino on piano. Guitar Slim's 'The Things That I Used to Do' (1953), with a 21-year-old Ray Charles on piano, went #1 R&B for 14 weeks.

Behind them all was the system: Dave Bartholomew assembled the house band, wrote the hits, and connected artists to Imperial Records in Los Angeles. A studio, a producer, a house band, a label relationship—every major R&B city would replicate this New Orleans model, but none would match the original's density of innovation.

WhyArts, CC BY-SA 4.0

Cosimo Matassa

The Teen Engineer

Opened J&M Recording Studio at age 18 in 1945. Recorded virtually every New Orleans R&B hit through the 1970s. Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2012 for his foundational contributions.

Roland Godefroy, CC BY-SA 3.0

Fats Domino

The Rolling Piano

'The Fat Man' (1949) was a million-seller crossover hit. Sold 65+ million records—more than any 1950s artist except Elvis. His rolling triplet piano style became the New Orleans signature sound.

Memphis Soul Stew

Stax, Hi Records, and the Southern Sound (1957–1975)

“As you go down the slope, the music gets bigger, it separates.”

— Willie Mitchell, on Royal Studios' acoustics

Memphis developed two distinct but interrelated sounds, both shaped by physical architecture and racial geography. At Stax Records—housed in the Capitol Theatre, a converted 1920s movie theater on McLemore Avenue in South Memphis—the sloped floor created unique acoustics that producer Jim Stewart accidentally discovered enhanced the natural reverb. The integrated house band Booker T. & the M.G.'s (two Black musicians, two white) backed virtually every recording from 1962 onward. The result was grittier, rawer than Motown's polished Northern sound: Steve Cropper's delayed backbeat guitar, the Memphis Horns' punch, and vocals left deliberately unpolished.

Across town at Royal Studios—also a converted theater, where Willie Mitchell had recorded since 1957—a different Memphis emerged. Mitchell discovered Al Green singing at a 1969 Texas concert and signed him immediately. Together they created smooth Southern soul: strings layered over rhythm, vocals floating above the groove. 'Let's Stay Together' (1971) went #1 pop and R&B simultaneously, proving that Memphis could produce sophistication alongside raw emotion.

The business structures differed critically. Stax was Black-owned (after Jim Stewart's sister Estelle Axton sold her share); Hi Records, which distributed Royal's output, was not. When Stax lost its distribution deal with Atlantic in 1968, the label discovered Atlantic owned its entire back catalog—every Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, and Booker T. recording. The 1972 distribution deal with CBS Records that followed proved disastrous: CBS advanced $6 million but demanded impossible sales targets.

On December 19, 1975, Stax Records filed for bankruptcy. Union Planters Bank seized the building. The equipment was auctioned. Al Bell, who had built the company into a $30 million operation, faced federal charges (later acquitted). The collapse exposed what the music had always obscured: in America's music industry, Black-owned labels operated with margins so thin that a single bad deal could erase decades of work.

Stax Records, Public Domain

Otis Redding

The King of Soul

Stax Records' biggest star. '(Sittin' On) The Dock of the Bay' went #1 posthumously after his death in a plane crash at age 26. His raw emotional delivery defined Southern soul.

“These arms of mine, they are lonely...”

Bryan Ledgard, CC BY 2.0

Booker T. Jones

The M.G.'s Architect

Led Booker T. & the M.G.'s, the integrated house band that backed virtually every Stax recording. Composed 'Green Onions.' Their interracial collaboration was revolutionary in the segregated South.

“We were a family. Black and white didn't matter in that studio.”

Mike Douglas Show, Public Domain

Al Green

The Smooth Reverend

'Let's Stay Together' (1971), 'Love and Happiness' (1972). Left secular music for ministry in 1979, returning partially. His falsetto and intimate delivery at Royal Studios created smooth Southern soul.

Hitsville U.S.A.

Motown and the Detroit Assembly Line (1959–1972)

“I realized that a hit record was a product of its own.”

— Berry Gordy

Berry Gordy borrowed $800 from his family's savings club—the Ber-Berry Co-Op—on January 12, 1959, and built an empire worth $61 million by the time he sold it in 1988. Motown's genius was applying Detroit's automotive assembly-line principles to music: quality control meetings every Friday morning where producers competed to get their songs released, in-house production that controlled every element, artist development through charm school training, and relentless polish that made the final product radio-ready for any market.

In Studio A—nicknamed 'The Snake Pit' for its claustrophobic 22-by-14-foot dimensions—the Funk Brothers created the sound that defined an era. Between 1959 and 1972, this rotating collective of session musicians played on more #1 pop hits than the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Beach Boys, and Elvis Presley combined. The numbers are staggering: an estimated 57 chart-topping songs. Yet they were paid $10 per song—the same rate whether the song sold 500 copies or 5 million. They received no royalties. They were not credited on album covers until 'What's Going On' in 1971, twelve years and countless hits after Motown's founding.

Motown's charm school, run by Maxine Powell, taught artists to appeal to white audiences: proper diction to minimize Southern accents, choreography courtesy of Cholly Atkins, and etiquette lessons for television appearances and white supper clubs. It was crossover by design—not changing the music's essence but packaging its presentation. The strategy worked: between 1961 and 1971, Motown placed 110 singles in the pop Top Ten.

But empires relocate. In June 1972, Gordy moved Motown's operations to Los Angeles to pursue film and television. The Funk Brothers discovered this when they arrived at Hitsville and found a notice on the studio door. Most stayed in Detroit; the hits migrated west. By 1988, when Gordy sold Motown to MCA Records, only the building at 2648 West Grand Boulevard remained—now a museum to what had been, just two decades earlier, the most successful Black-owned business in America.

Angela George, CC BY-SA 3.0

Berry Gordy

The Mogul

Founded Motown Records with an $800 family loan in 1959. Created the 'assembly line' approach to hit-making. Sold Motown to MCA for $61 million in 1988. Built the most successful Black-owned business in America.

Jeff Albert, CC BY-SA 2.0

The Funk Brothers

The Invisible Hit Makers

Motown's house band—James Jamerson (bass), Benny Benjamin (drums), Earl Van Dyke (keys), and others. Played on more #1 hits than any group in history. Not credited until 1971. Documented in 'Standing in the Shadows of Motown' (2002).

“We played on everything. We were Motown.”

NBC Television, 1970, Public Domain

Smokey Robinson

The Poet Laureate

The Miracles frontman and Motown VP. Wrote 'My Girl,' 'The Tracks of My Tears,' and countless hits for other artists. Bob Dylan called him 'America's greatest living poet.'

The Philadelphia Sound

Sigma Sound and Soul in a Tuxedo (1968–1979)

“Soul music in a tuxedo.”

— Joe Tarsia, on the Philadelphia Sound

Philadelphia developed R&B's most sophisticated sound by design rather than accident. At Sigma Sound Studios—a converted warehouse at 212 North 12th Street that Joe Tarsia opened in 1968—producer Thom Bell and songwriter-producers Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff orchestrated what became 'soul in a tuxedo.' Where Motown had polished its sound for crossover, Philadelphia elevated it: full orchestral arrangements, complex chord progressions borrowed from jazz and classical music, and lyrics that addressed social issues without sacrificing danceability.

The infrastructure was unprecedented. MFSB—variously said to stand for 'Mother Father Sister Brother' or Philadelphia's response to the question 'What does MFSB mean?'—was a 30-plus member orchestra that included players from the Philadelphia Orchestra alongside R&B session veterans. This ensemble played on every Philadelphia International hit: The O'Jays' 'Love Train' (1972), Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes' 'If You Don't Know Me by Now' (1972), and Billy Paul's 'Me and Mrs. Jones' (1972, #1 pop and R&B for three weeks).

MFSB's own recording 'TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia)' became the theme for Don Cornelius's Soul Train in 1974—the first television theme song ever to reach #1 on the pop charts. The success validated Gamble and Huff's theory: you could make Black music more sophisticated without making it less Black. It was crossover by elevation rather than dilution.

But the model proved fragile. A 1975 payola investigation (Gamble pleaded no contest to a single count) damaged the label's momentum. Disco's rise fragmented the market. By 1980, Philadelphia International had ceased to be a hitmaking force, though its influence would echo through every R&B production that followed—from Quiet Storm to New Jack Swing to contemporary R&B's continued emphasis on lush, layered production.

John Mathew Smith, CC BY-SA 2.0

Gamble and Huff

The Architects of Philadelphia Soul

Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff founded Philadelphia International Records in 1971. Wrote and produced 'If You Don't Know Me by Now,' 'Love Train,' 'For the Love of Money.' Their orchestral approach defined 1970s R&B sophistication.

“We wanted to bring Black music to the world without losing its soul.”

Thom Bell

The Quiet Genius

Produced The Stylistics, The Spinners, Elton John. His lush arrangements and meticulous production defined the Philadelphia Sound's elegance.

“To put it in a nutshell, he's responsible for everything that's happened to me in my career. — Russell Thompkins Jr.”

The Invisible Engine

Session Musicians and the Economics of Credit (1950–Present)

Every major R&B sound was built by largely uncredited session musicians whose names never appeared on the records they made essential. The Funk Brothers at Motown played on an estimated $1 billion worth of music. Booker T. & the M.G.'s created the Stax sound heard on over 600 recordings. MFSB in Philadelphia orchestrated the arrangements that made the city's music distinctive. The Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section (the Swampers) backed Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, and dozens more. These bands created the sounds that made stars—and remained invisible while doing so.

The economics were brutal. At Motown, the Funk Brothers were paid $10 per song—a flat rate whether the recording sold 500 copies or 5 million. Union scale at the time was approximately $60 per three-hour session; Motown paid less and demanded exclusivity. There were no royalties: James Jamerson's bass line on 'What's Going On' helped sell 2 million copies, for which he received nothing beyond his session fee. At Stax, Booker T. Jones and the M.G.'s had a slightly better arrangement as signed artists, but their session work for others followed the same pattern.

This invisibility was structural, not accidental. The 'artist' model of popular music requires a face, a name, a story to sell—someone for fans to identify with, for magazines to photograph, for concerts to feature. The musicians who actually played the music were hidden behind that story. Album credits, when they existed, listed producers and occasionally arrangers; instrumentalists were afterthoughts at best, omitted entirely at worst.

It took decades for any correction to begin. Allan Slutsky's 1989 book 'Standing in the Shadows of Motown' documented James Jamerson's contributions for the first time. The 2002 documentary of the same name brought surviving Funk Brothers to audiences who had never heard their names. But the correction came too late for many: Benny Benjamin died in 1969, James Jamerson in 1983, Earl Van Dyke in 1992—all before the full scale of their contribution was publicly recognized.

James Jamerson

The Phantom Bassist

Motown's principal bassist. Played on more #1 hits than any instrumentalist in history. Developed the melodic bass style that influenced all pop music. Never credited on albums. Struggled financially late in life.

Benny Benjamin

Papa Zita

Motown's principal drummer. Invented the 'Motown beat' that drove hundreds of hits. Died at 43, never seeing his influence recognized. The heartbeat of Motown.

Technology as Instrument

From Electric Guitar to Auto-Tune (1940–Present)

R&B's evolution tracks precisely with technological change, with each major innovation not merely changing the sound but creating entirely new eras. The pattern is consistent: technology arrives, early adopters experiment, a breakthrough record demonstrates the possibilities, and the genre transforms. Understanding this pattern is essential to understanding why R&B sounds the way it does—and why debates about 'real' R&B inevitably founder on the reality of technological determinism.

Electric amplification in the 1940s allowed solo instruments to compete with big bands—T-Bone Walker's electric guitar could cut through a horn section. Multitrack recording, pioneered by Les Paul in 1948 but not widely available until the late 1950s, enabled layered production where a single artist could sound like an ensemble. Synthesizers entered R&B through Stevie Wonder's partnership with TONTO (The Original New Timbral Orchestra), a massive modular synthesizer he used on 'Music of My Mind' (1972) and 'Innervisions' (1973). Wonder proved that synthesizers could convey warmth and soul, not just cold electronic tones.

Drum machines transformed everything between 1980 and 1982. The Roland TR-808, released in 1980, was initially considered a failure—its sounds were too artificial for studios seeking realistic drums. But producers discovered that artificiality could be a feature: the 808's deep bass kick and snappy snare became R&B signatures. Marvin Gaye's 'Sexual Healing' (1982), produced in Belgium with the TR-808, became the first American hit to feature the machine prominently—and crucially, the first to use it as an instrument of intimacy rather than cold rhythm. The track spent 10 weeks at #1 R&B and shifted the genre's entire trajectory toward electronic production.

Auto-Tune arrived in 1997, created by Andy Hildebrand, a former Exxon engineer who used algorithms developed for seismic data interpretation to analyze and correct vocal pitch. 'I put that setting in the software,' Hildebrand later admitted about the 'zero' correction speed that creates the robotic effect. 'But I didn't think anyone in their right mind would ever use it.' Cher's 'Believe' (1998) proved him wrong, and within five years Auto-Tune had become as standard in R&B production as reverb—another technology that fundamentally altered what the genre could sound like.

Antonio Cruz/ABr, CC BY 3.0 BR

Stevie Wonder

The Synthesizer Pioneer

'Music of My Mind' (1972) was the first classic album integrating the TONTO synthesizer. Proved synthesizers could convey soul and emotion, not just cold electronica. Revolutionized what R&B could sound like.

“I wanted to use technology to expand what the human spirit could express.”

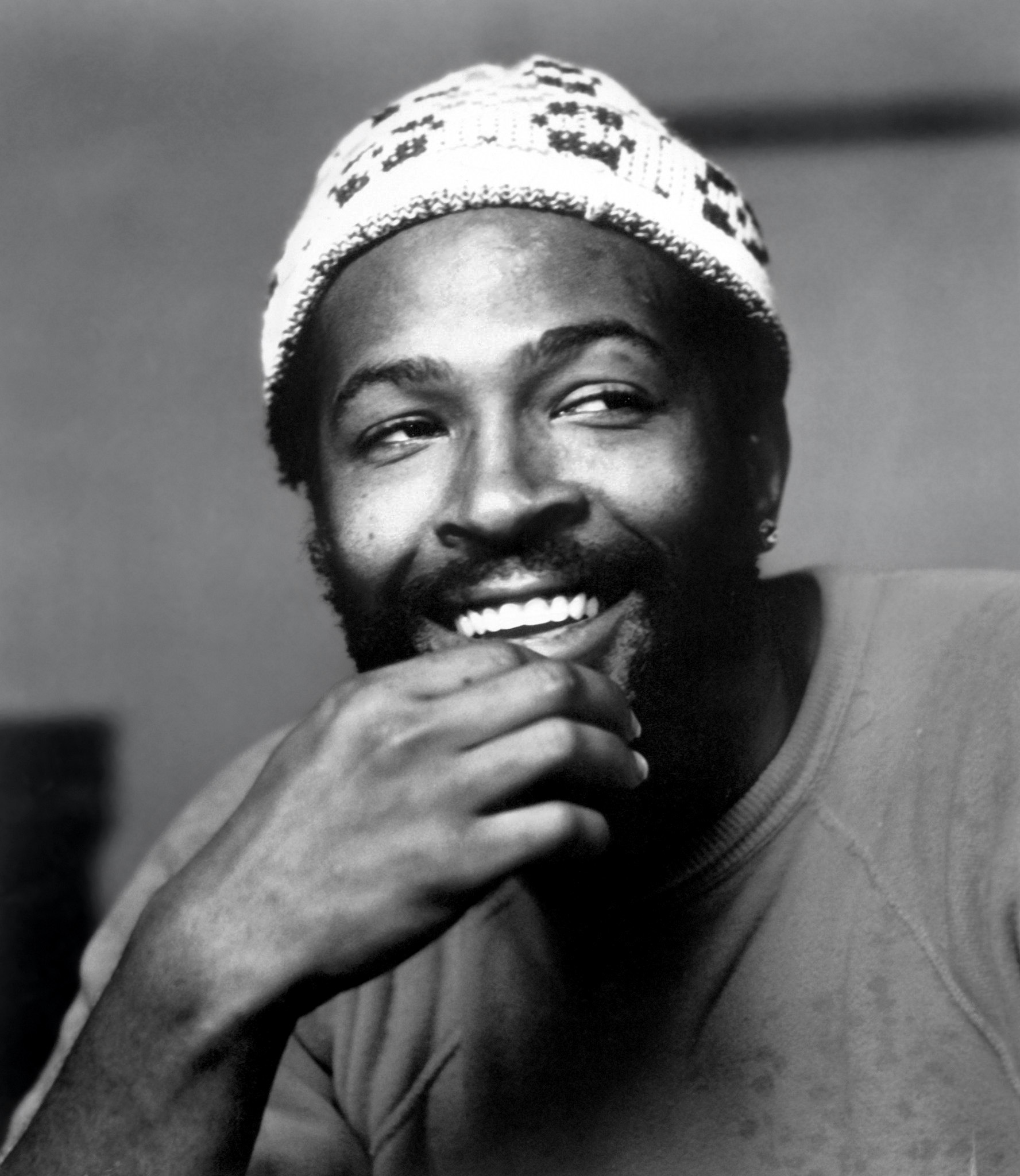

Jim Britt, Public Domain

Marvin Gaye

The 808 Intimist

'Sexual Healing' (1982) was the first US hit to feature the TR-808. Made drum machines sensual rather than mechanical. Proved technology could serve intimacy.

Women as Architects

Builders, Not Appendices (1940s–Present)

R&B history as typically written centers male producers and executives—Berry Gordy, Quincy Jones, Teddy Riley, Babyface. But women were equally foundational to the genre's development, though their contributions were systematically undervalued, undercredited, and undercompensated. The pattern repeats across decades: women doing essential work while men received the public recognition and the business equity.

Ruth Brown didn't just sing for Atlantic—she built it, generating the revenue that funded the label's expansion from a jazz boutique into an R&B powerhouse. Her consecutive #1 hits from 1950 to 1954 financed Atlantic's ability to sign Ray Charles and develop him into a crossover star. Then, in 1987, she co-founded the Rhythm and Blues Foundation specifically to recover unpaid royalties—not just for herself, but for dozens of artists whose contracts had been written to benefit labels at artists' expense.

Sylvia Robinson's contributions span decades and genres. As half of Mickey & Sylvia, she had a #1 hit with 'Love Is Strange' (1956). As a label owner at Sugar Hill Records in 1979, she conceived, assembled, and produced 'Rapper's Delight'—hip-hop's first hit record—when her male peers considered rap a fad. Three years later, she produced 'The Message' (1982), hip-hop's first socially conscious hit. Without her vision and risk-taking, hip-hop's recorded history might have unfolded entirely differently.

The business barriers persisted longer. Sylvia Rhone became the first African-American woman to run a major label when she took over Elektra Records in 1994. By then, women had been shaping R&B for 45 years—as singers, as songwriters, as producers, as arrangers—but the executive suites remained largely closed. Missy Elliott summarized the disparity in a 2016 Billboard interview: 'A lot of people don't know a lot of records that I've written or produced... I always said if a man would have done half the records that I've done we would know about it. But we don't know all the records I've done for other artists.'

Atlantic Records, CC0

Aretha Franklin

The Queen of Soul

'Respect' (1967) became a feminist and civil rights anthem. First woman inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (1987). Her creative control at Atlantic—sitting at the piano, bringing her own arrangements—changed what was possible for women in R&B.

“It was the need of a nation, the need of the average man and woman in the street.”

Sylvia Robinson

The Godmother of Hip-Hop

Co-founded Sugar Hill Records. Produced 'Rapper's Delight' (1979) and 'The Message' (1982). Created hip-hop's recorded form before anyone else saw its potential.

Atlantic Records, CC BY-SA 4.0

Missy Elliott

The Producer Who Proved It

First female rapper inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (2022). Produced and wrote for countless artists while building her own career. Made the invisible work of women producers visible.

“I knew I would have to produce. I didn't want to just be an artist and let someone else have all that control.”

The Symbiosis

R&B and Hip-Hop Co-Evolution (1979–1999)

“New Jack Swing is a movement... When you're doing New Jack Swing, you're doing a singer and a rapper together.”

— Teddy Riley

The narrative that 'hip-hop killed R&B' is historically illiterate. The genres have been in continuous mutual exchange since hip-hop's recorded origins, with each borrowing from and enhancing the other. Understanding this symbiosis is essential to understanding why contemporary R&B sounds the way it does—and why attempts to separate the genres are exercises in nostalgia rather than analysis.

Hip-hop sampled R&B from its founding moment. DJ Kool Herc's legendary 1973 parties in the Bronx featured extended breaks from funk and soul records—James Brown, The Incredible Bongo Band, The Honeydrippers. The entire foundation of hip-hop production rested on R&B's rhythmic innovations. When Sugar Hill Records released 'Rapper's Delight' in 1979, the backing track was Chic's 'Good Times'—an R&B #1 hit from earlier that year. The relationship was parasitic in the technical sense: hip-hop fed on R&B's body of work.

R&B returned the favor starting in 1987, when Teddy Riley's production for Keith Sweat's 'I Want Her' introduced New Jack Swing—R&B vocals over hip-hop beats, swung rather than straight, with programmed drums replacing live percussion. Riley's subsequent work with Bobby Brown, Guy, and Michael Jackson's 'Dangerous' album established the template. The relationship became bidirectional: R&B provided melodic and harmonic vocabulary; hip-hop provided rhythmic and production vocabulary.

Mary J. Blige's 'What's the 411?' (1992), produced largely by Sean 'Puffy' Combs, is credited with inventing hip-hop soul as a distinct subgenre. But the album wasn't hip-hop taking over R&B—it was a genuine hybrid created by an R&B vocalist with impeccable soul credentials working over hip-hop production that sampled soul records. The circle was complete: hip-hop sampling R&B, used to back an R&B vocalist, creating something neither genre could have produced alone.

On December 11, 1999, Billboard officially recognized what had been obvious for a decade: the R&B chart became 'Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs.' The genres had been evolving together since at least 1987; the industry infrastructure finally caught up with the artistic reality.

U.S. Navy/Donna Lou Morgan, Public Domain

Mary J. Blige

The Queen of Hip-Hop Soul

'What's the 411?' (1992) invented hip-hop soul. Combined R&B vocals with hip-hop production, street authenticity with emotional vulnerability. Created a template that dominates contemporary R&B.

“I started speaking about what I was dealing with through my music, and 4 million women responded and said, 'Us too, Mary.'”

Christopher Diont'e, CC BY-SA 4.0

Teddy Riley

The New Jack Swing Architect

Created the New Jack Swing sound that fused R&B with hip-hop rhythms. Produced Keith Sweat, Bobby Brown, Michael Jackson's 'Dangerous.' Built the bridge between genres.

Collision Conf, CC BY 2.0

Timbaland

The Sound of the Future

Produced Aaliyah, Missy Elliott, Justin Timberlake. Pioneered sample-heavy, rhythmically complex production that pushed R&B into the future. 'You will play her songs for 20 years... She is the Aretha Franklin of hip-hop.' (on Missy Elliott)

Crossover Economics

Race, Money, and the Mainstream (1950–Present)

'Crossover' in R&B has always carried a specific economic meaning: music created by Black artists reaching white audiences and white-controlled radio formats through either controlled sanitization, strategic positioning, or sheer undeniability. The term itself reveals the industry's architecture—Black music 'crossing over' into the mainstream, as if the mainstream were the natural state and Black audiences a specialty market to be transcended.

In the 1950s, the crossover dynamic was nakedly exploitative. White artists like Pat Boone recorded note-for-note covers of Black originals specifically for segregated radio stations that wouldn't play Black artists. Little Richard's 'Tutti Frutti' and Fats Domino's 'Ain't That a Shame' both had their sales cannibalized by Boone covers that reached audiences the originals couldn't access. LaVern Baker watched Georgia Gibbs copy her arrangement of 'Tweedle Dee' measure for measure and outsell her—leading Baker to petition Congress in 1955 for arrangement copyright protection. She failed; the law wouldn't protect arrangements for another decade.

The economic violence extended beyond covers. Big Mama Thornton recorded 'Hound Dog' in August 1952 at Radio Recorders in Los Angeles. The single went to #1 R&B and sold approximately 2 million copies. Thornton received a single check for $500—her only payment for a song that would become, in Elvis Presley's 1956 version, one of the best-selling singles in recording history. 'That song sold over 2 million records,' Thornton told interviewers in the 1980s. 'I got one check for $500 and never saw another.' She died in 1984, in a boarding house in Los Angeles, essentially penniless.

The pattern persisted across decades. Artists who successfully crossed over—Diana Ross, Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, Beyoncé—earned more money than those who didn't. But crossover often required softening cultural specificity for white comfort, and even successful crossover rarely translated into Black ownership of the infrastructure. The industry extracted value from Black creativity while ensuring that the executives, the label owners, the publishing companies, and the distribution networks remained overwhelmingly white.

Reitz, CC BY-SA 3.0

Big Mama Thornton

The Original Hound Dog

Recorded the original 'Hound Dog' (1952), #1 R&B for 7 weeks. Received only $500 while Elvis Presley's cover became one of the best-selling singles ever. Her exploitation became emblematic of the industry's treatment of Black artists.

“That song sold over 2 million records. I got one check for $500 and never saw another.”

Philip Spittle, CC BY 2.0

Tina Turner

The Comeback Queen

Left Ike Turner in 1976 with '36 cents and a gas station credit card.' 'Private Dancer' (1984) at age 45 sold 20 million copies. Proved crossover didn't require compromising power.

“I had to go out in the world and become strong, to discover my mission in life.”

The Myth of Real R&B

Authenticity Cycles and Continuous Reinvention

“When you try to label it, you remove the option for it to be limitless. It diminishes the music.”

— SZA

Every generation believes the previous generation's R&B was 'real' and the current generation is corrupted. This pattern has repeated without exception for 75 years, and understanding its persistence is essential to understanding why debates about R&B's authenticity are ultimately debates about generational identity rather than musical quality.

The cycle follows a predictable pattern. In the 1960s, purists complained that soul music was too smooth—jump blues and early R&B had real energy. In the 1970s, classic soul was 'real'; disco was sellout music made for white audiences. In the 1980s, Motown and Stax were authentic; synthesizers and drum machines had ruined the warm sound of live musicians. In the 1990s, quiet storm and ballad R&B were 'real'; hip-hop was taking over and corrupting the genre. In the 2000s, 90s hip-hop soul was authentic; Auto-Tune had ruined actual singing. In the 2010s, 2000s R&B was 'real'; alternative R&B—The Weeknd, Frank Ocean, SZA—wasn't really R&B at all.

The evidence against these authenticity claims is overwhelming. Technology has always shaped R&B sound: electric guitars in the 1940s, multitrack recording in the 1960s, synthesizers in the 1970s, drum machines in the 1980s, sampling in the 1990s, Auto-Tune in the 2000s. Each era produced enduring classics alongside forgettable product—exactly as every era does. Artists dismissed as 'not real R&B' in their time (Prince in the 1980s, Mary J. Blige in the 1990s, Beyoncé in the 2000s) became the standard against which subsequent generations were measured.

What authenticity claims actually reveal is genre boundary policing—attempts to preserve a particular sound associated with a particular generation's coming-of-age. The R&B that sounds 'real' to a given listener is typically the R&B they encountered between ages 15 and 25. This is not a criticism; it is simply how musical taste functions. But mistaking personal nostalgia for objective assessment produces the same complaint every generation: 'R&B was better when...' R&B's continuous reinvention isn't a bug to be fixed. It is the defining feature of a genre that has never stopped evolving since Jerry Wexler first gave it a name.

Raph_PH, CC BY 4.0

SZA

The Genre Refuser

'Ctrl' (2017) sold 3.5+ million copies, bringing alternative R&B to the mainstream. First female artist at TDE (Top Dawg Entertainment). Refuses genre categorization as limiting.

Andras Ladocsi, CC BY-SA 4.0

Frank Ocean

The Alternative Pioneer

'channel ORANGE' (2012) and 'Blonde' (2016) redefined what R&B could be. His introspective, experimental approach helped establish 'alternative R&B' as a recognized movement.

The Feeling Itself

In 1949, Jerry Wexler gave a name to music that already existed. That name created a category, and that category created an industry, and that industry created wealth (mostly for others) and art (mostly from Black creators).

R&B didn't die—it did something more profound. It taught pop how to feel. The melismatic vocals, the groove-based rhythm, the emotional directness, the technological innovation—all of this is now standard in popular music. R&B won so completely that it became invisible, absorbed into the mainstream.

But the genre persists. In bedroom studios and major labels, artists continue to make music they call R&B. They argue about what it means. They claim authenticity. They innovate. The vinyl still spins. The groove still hits.

The heartbeat continues.

Output / Sources & Further Reading

Books

Archives & Institutions

Image Credits

All images sourced from Wikimedia Commons. Click subject names to view original files.

- Ruth Brown— caviera, CC BY 2.0

- Cosimo Matassa— WhyArts, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Fats Domino— Roland Godefroy, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Stax Museum— Thomas R Machnitzki, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Otis Redding— Stax Records, Public Domain

- Booker T. Jones— Bryan Ledgard, CC BY 2.0

- Al Green— Mike Douglas Show, Public Domain

- Hitsville U.S.A.— Blob4000, Public Domain

- Berry Gordy— Angela George, CC BY-SA 3.0

- The Funk Brothers— Jeff Albert, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Smokey Robinson— NBC Television, Public Domain

- Gamble & Huff— John Mathew Smith, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Roland TR-808— Eriq, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Stevie Wonder— Antonio Cruz/ABr, CC BY 3.0 BR

- Marvin Gaye— Jim Britt, Public Domain

- Aretha Franklin— Atlantic Records, CC0

- Missy Elliott— Atlantic Records, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Mary J. Blige— U.S. Navy/Donna Lou Morgan, Public Domain

- Teddy Riley— Christopher Diont'e, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Timbaland— Collision Conf, CC BY 2.0

- Big Mama Thornton— Reitz, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Tina Turner— Philip Spittle, CC BY 2.0

- SZA— Raph_PH, CC BY 4.0

- Frank Ocean— Andras Ladocsi, CC BY-SA 4.0