ארץ/فلسطين

A Land of Many Names, A People's Many Griefs

From Deep Antiquity to Today

The Land Before Flags

Geography and Environment

Before any people claimed this land, the land itself shaped what would happen.

The geography explains everything: a narrow coastal plain, a spine of hills running north-south, a deep rift valley, and desert to the east. The only fertile corridor between Egypt and Mesopotamia—anyone wanting to move armies or trade goods between the great civilizations had to pass through here.

This made the land strategically vital for empires and exposed to constant conquest. For four thousand years, armies have marched through this corridor: Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Greek, Roman, Arab, Crusader, Ottoman, British. The same 60 miles, again and again.

60 miles from the Mediterranean to the Jordan River. This is what everyone has fought over for 4,000 years.

Water scarcity meant settlements clustered around springs and seasonal streams. The limestone hills collected rainwater in cisterns. Olive trees, grapevines, wheat, and barley could grow here—but barely. Pastoralism and agriculture coexisted, sometimes uneasily.

Jerusalem's location makes no geographic sense—no river, no major trade route. But it sits on a defensible ridge, with water access (the Gihon Spring), between the northern tribes and the southern. It became holy not despite its marginality but because of it: a place for pilgrimage, not commerce.

The Levant—the narrow corridor between Egypt and Mesopotamia that shaped four thousand years of history.

NASA/Wikimedia Commons · Public Domain

Jerusalem sits on a defensible ridge in the Judean Hills—holy not despite its marginality, but because of it.

Wikimedia Commons · CC BY-SA

The Jordan Rift Valley—the dramatic geological boundary that defines the land's eastern edge.

Wikimedia Commons · CC BY-SA 2.0

Deep Antiquity

Archaeological Record (Before 1200 BCE)

Human habitation here stretches back 10,000+ years. By the Bronze Age (3300-1200 BCE), the land was home to Canaanite city-states that traded with Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Megiddo, Hazor, Jericho, Jerusalem, Gaza—these were thriving cities with temples and palaces. The Canaanites were not one people but many: city-dwellers, farmers, pastoralists, speaking related Semitic languages, worshipping El and Baal.

Egypt dominated during much of this period. The Amarna Letters (14th century BCE) show local kings writing to Pharaoh, pleading for help against rivals. One letter from Abdi-Heba, king of Jerusalem, reads: “Neither my father nor my mother set me in this place—the arm of the mighty king installed me.”

“Neither my father nor my mother set me in this place—the arm of the mighty king installed me.”

— Abdi-Heba, King of JerusalemAmarna Letter to Pharaoh Akhenaten, c. 1350 BCE

The Bronze Age collapsed around 1200 BCE. Invasion, drought, trade disruption—scholars debate the causes. But the old Canaanite city-states fell. Into this vacuum came new peoples: Israelites from the hill country, Philistines from the sea.

The Merneptah Stele (c. 1208 BCE)—the earliest known reference to 'Israel' outside the Bible.

Egyptian Museum, Cairo · Public Domain

Tel Megiddo—a Bronze Age city-state that controlled the vital pass between Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Government Press Office of Israel · CC BY-SA 2.0

An Amarna Letter—cuneiform tablets from local kings to Pharaoh, including pleas from Jerusalem's ruler.

British Museum/Wikimedia · Public Domain

Peoples of the Iron Age

Canaanites, Israelites, Philistines (1200-586 BCE)

The Iron Age saw the emergence of peoples whose names still echo today. But ancient peoples do NOT map neatly onto modern national identities.

The Canaanites did not disappear. Genetic studies show substantial continuity between Bronze Age Canaanites and modern Levantine populations—Lebanese, Jews, and Palestinians all share significant Canaanite ancestry.

“Most of today's Jewish and Arabic-speaking populations share a strong genetic link to the ancient Canaanites.”

— PMC genetic studyBased on ancient DNA analysis

Israelite identity emerged gradually from within this Canaanite context, not through sudden conquest. Israeli archaeologist Israel Finkelstein's research demonstrates: the settlers were likely “indigenous to Canaan... pastoralists who lived on the fringes of settled areas.”

The Philistines—Sea Peoples who arrived around 1175 BCE—settled the southern coast. Despite distinct origins, they quickly intermarried with local populations. The name “Palestine” derives from “Philistines” via Greek.

The kingdoms of Israel (north) and Judah (south) rose and fell. Assyria destroyed Israel in 722 BCE. Babylon conquered Judah in 586 BCE, destroying the First Temple and deporting elites.

Critical finding: Population continuity and mixture, not replacement, characterizes this region's history. Both Jewish and Arab populations today share substantial Canaanite ancestry.

Ancient Canaan—home to diverse peoples whose descendants still live here today.

Wikimedia Commons · CC BY-SA

Egyptian relief depicting the 'Sea Peoples' including the Peleset—whose name became 'Palestine.'

Wikimedia Commons · Public Domain

Philistine pottery with distinctive Aegean-influenced designs—evidence of the Sea Peoples' Mediterranean origins.

Wikimedia Commons · CC BY-SA

Rome and Renaming

Roman/Byzantine & 'Palaestina'

Rome arrived in 63 BCE, when Pompey conquered Jerusalem. For the next seven centuries, this land would be part of the Roman (later Byzantine) Empire.

The Jewish population revolted repeatedly. The Great Revolt (66-73 CE) ended with Jerusalem's destruction and the Temple's burning, depicted on the Arch of Titus in Rome.

The Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-135 CE) was crushed even more brutally. After this, Emperor Hadrian renamed Jerusalem “Aelia Capitolina” and the province “Syria Palaestina”—after the Philistines, Israel's ancient enemies. The renaming was deliberate humiliation.

“All the rest of the wall encompassing the city was so completely levelled to the ground as to leave future visitors to the spot no ground for believing that it had ever been inhabited.”

— JosephusThe Jewish War, Book VII (75 CE)

The Jewish population diminished but did not disappear. Communities remained, especially in Galilee. The Mishnah and Palestinian Talmud were compiled here. But Jews were now a minority in a land renamed to erase them.

Christianity changed everything. After Constantine's conversion (312 CE), Palestine became the Holy Land—a Christian pilgrimage destination. Churches rose over sites of Jesus's life.

Key note: The name “Palestine” comes from this Roman renaming. It is not invented in the 20th century. But neither is it neutral—it was chosen to displace Jewish identity.

The Arch of Titus in Rome—Roman soldiers carry the Temple's menorah after Jerusalem's destruction in 70 CE.

Wikimedia Commons · Public Domain

A coin from the Bar Kokhba revolt (132-135 CE)—the last Jewish rebellion against Rome.

Wikimedia Commons · CC BY-SA

The Madaba Map (6th century CE)—a Byzantine mosaic showing the Holy Land with Jerusalem at center.

St. George's Church, Madaba · Public Domain

The Islamic Centuries

Arab Conquest to Ottoman Arrival

Arab armies conquered Palestine in 636-640 CE. The transformation that followed was gradual but profound.

Over centuries, the population—previously Greek-speaking Christian and Aramaic-speaking Jewish—became predominantly Arabic-speaking Muslim. This happened through conversion, intermarriage, immigration, and cultural absorption—not mass population replacement.

The process was not forced en masse. Christians and Jews were dhimmis—protected peoples who paid special taxes but could practice their faiths. But over centuries, conversion offered social and economic advantages.

Jerusalem was sacred to Muslims as well—the site of Muhammad's Night Journey. The Dome of the Rock (691 CE) and Al-Aqsa Mosque were built on the Temple Mount / Haram al-Sharif. The layering of holiness on holiness would become one of history's most explosive inheritances.

The Crusades (1099-1291) brought European Christian rule for two centuries—brutal conquest followed by complex coexistence. The 1099 massacre saw Jews and Muslims slaughtered in the city. Saladin's reconquest (1187) was notably less violent—ransomed rather than massacred.

“In the Temple and porch of Solomon, men rode in blood up to their knees and bridle reins.”

— Raymond of AguilersCrusader chronicler on the 1099 massacre (imagery drawn from Revelation 14:20)

Critical finding: The Arab conquest was not “replacement.” Modern Palestinians' ancestors are largely the same population as Byzantine Palestine—transformed by Arabization and Islamization.

The Dome of the Rock (691 CE)—built on the Temple Mount, where holiness was layered upon holiness.

Wikimedia Commons · CC BY-SA

Al-Aqsa Mosque—the third holiest site in Islam, destination of Muhammad's Night Journey.

David Shankbone · CC BY-SA

Saladin—who reconquered Jerusalem in 1187, notably with less bloodshed than the Crusaders.

Wikimedia Commons · Public Domain

Ottoman Palestine

Four Centuries Under the Sultans

The Ottoman Empire conquered Palestine in 1516 and held it until 1917—four centuries of relative stability.

For most of this period, Palestine was a provincial backwater. The Ottomans divided it into administrative districts under the province of Syria. There was no single “Palestine” administrative unit.

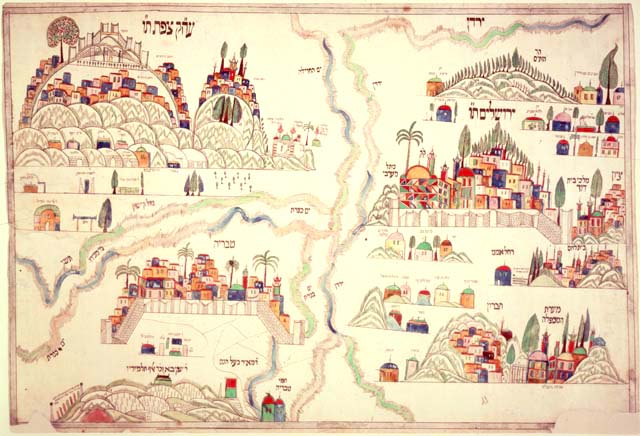

The population was predominantly Arab Muslim, with Christian Arab minorities and small Jewish communities in the “Four Holy Cities”—Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and Tiberias. These Jewish communities were mostly religious scholars supported by diaspora charity.

Life was agricultural, traditional, and local. Villages were organized around clan loyalties. Landlords owned large estates; peasants worked the land. Major changes were rare.

Everything changed in the late 19th century. Ottoman reform, European penetration, new land laws, and the arrival of the first Zionist immigrants began transforming the land.

Moses Montefiore (1784-1885)

British Jewish philanthropist who made seven trips to Palestine and built the first neighborhood outside Jerusalem's walls (Mishkenot Sha'ananim, 1860).

By 1914, the population was approximately 700,000-800,000, with about 60,000-85,000 Jews (roughly 8-10%).

Key finding: Ottoman Palestine was neither an independent state nor an empty land. It was a functioning agricultural society with established communities.

Jerusalem in 1870—a provincial Ottoman city, before the transformations to come.

Frederick Whitmore Holland · Public Domain

Jews praying at the Western Wall, 1870s—part of the small, traditional Jewish community that remained.

Felix Bonfils · Public Domain

A 19th century plaque depicting the 'Four Holy Cities'—Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and Tiberias.

Wikimedia Commons · Public Domain

Birth of Nationalisms

Competing National Projects

In the late 19th century, as nationalism swept the world, Jews and Arabs both developed modern national movements. Both focused on the same territory.

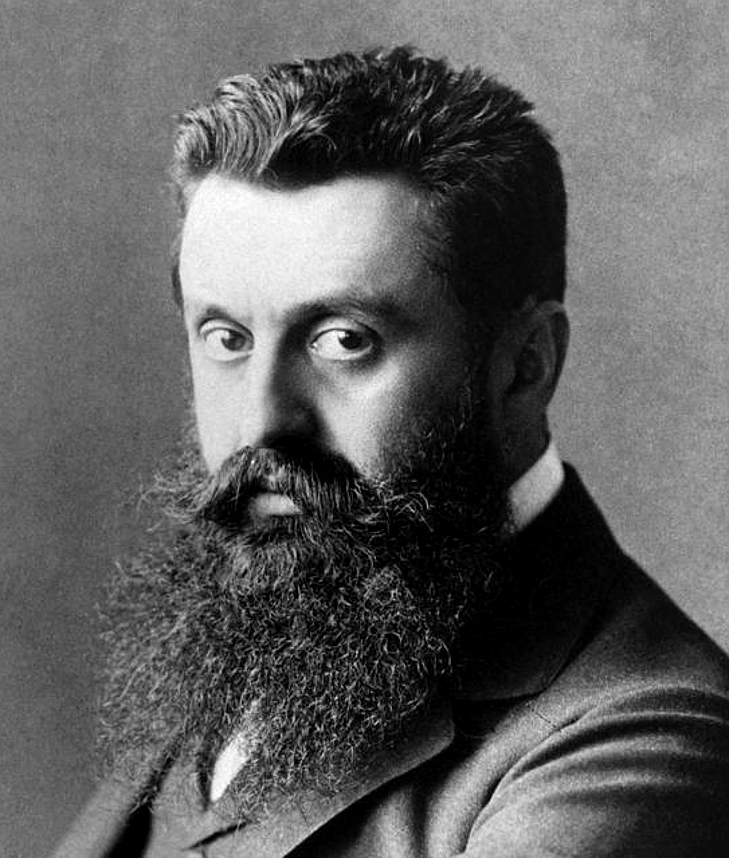

Political Zionism emerged primarily from European Jewish communities facing antisemitism. The Dreyfus Affair (1894) convinced Theodor Herzl that Jews would never be safe as minorities in Europe. The solution: a Jewish state in the ancestral homeland.

“At Basel I founded the Jewish state. If I said this out loud today I would be greeted by universal laughter. In five years perhaps, and certainly in fifty years, everyone will perceive it.”

— Theodor Herzl, 1897Israel was declared in 1948, 51 years later

The First Zionist Congress (1897) established the movement. Immigration began—first from Russia (escaping pogroms), then from across Europe. By 1914, about 85,000 Jews lived in Palestine.

Arab nationalism was awakening throughout the Ottoman Empire. In Palestine specifically, Arabs began noticing that these Jewish immigrants were not traditional religious pilgrims—they were settlers with national aspirations.

“We must surely learn, from both our past and present history, how careful we must be not to provoke the anger of the native people by doing them wrong.”

— Ahad Ha'am'Truth from Eretz Israel,' 1891

The first clashes occurred before World War I. Arab newspapers warned about land purchases. In 1891, Jerusalem notables petitioned Istanbul against Jewish immigration—one of the first documented Palestinian political acts regarding Zionism.

Key finding: Both nationalisms are modern constructions—like all nationalisms. This does not make either less real or less legitimate. The tragedy is that both movements claimed the same land.

Delegates at the First Zionist Congress, Basel 1897—'At Basel I founded the Jewish state.'

Wikimedia Commons · Public Domain

Theodor Herzl—the Viennese journalist who founded political Zionism after the Dreyfus Affair.

Wikimedia Commons · Public Domain

Jaffa and its orange groves—Palestine was neither empty nor undeveloped.

Library of Congress · Public Domain

The British Mandate

Promises, Contradictions, Violence

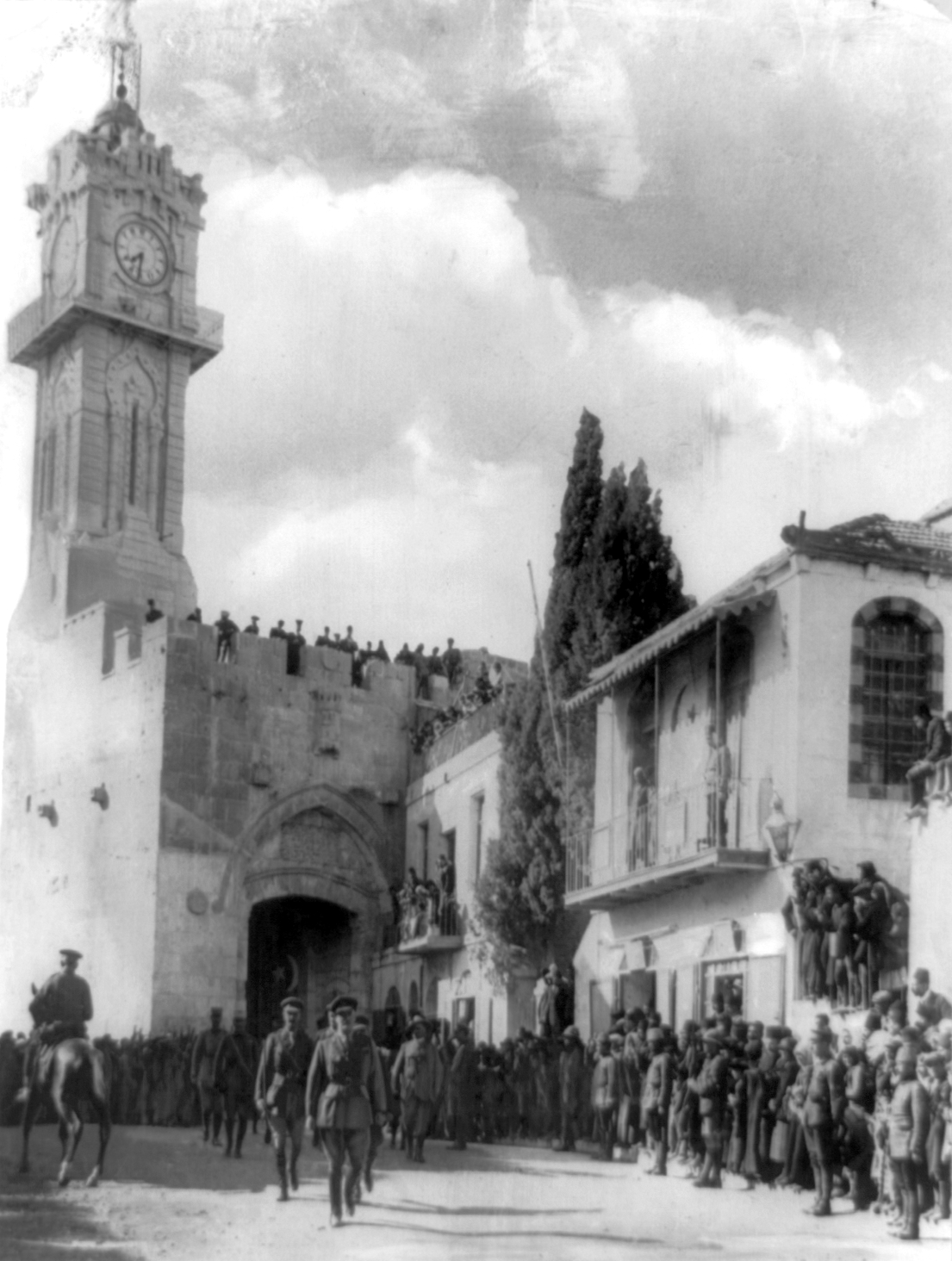

The Balfour Declaration of 1917 promised Jews a “national home” while pledging that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities.” This was contradiction, not compromise.

“His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people...”

— Balfour DeclarationNovember 2, 1917

Jewish immigration transformed demographics. From 11% Jewish in 1922 to 32% in 1947. Arab resistance grew—riots in 1920, 1921, 1929 (including the Hebron massacre of 67 Jews), and the full-scale Arab Revolt (1936-1939).

Britain's 1939 White Paper severely limited Jewish immigration just as European Jews desperately needed refuge—a decision that would cost hundreds of thousands of lives during the Holocaust.

“We will fight the war as if there were no White Paper, and we will fight the White Paper as if there were no war.”

— David Ben-Gurion, 1939

After WWII, with Holocaust survivors demanding entry, Jewish underground groups attacked British forces. The King David Hotel bombing (1946) killed 91. Britain, exhausted, handed the problem to the UN.

UN Resolution 181 (November 29, 1947) proposed partition: 56% to Jews (32% of population), 43% to Arabs, Jerusalem international. Jews accepted; Arabs rejected. Violence began immediately.

Critical finding: The Mandate's two promises could not both be fulfilled. A Jewish national home with significant immigration was incompatible with protecting Arab rights.

The Balfour Declaration (1917)—67 words that promised a 'national home' while protecting 'existing non-Jewish communities.'

British National Archives · Public Domain

General Allenby enters Jerusalem on foot, December 1917—the end of 400 years of Ottoman rule.

Library of Congress · Public Domain

Palestinian rebels during the Arab Revolt (1936-1939)—the first major uprising against British rule and Zionism.

Wikimedia Commons · Public Domain

1948

Holocaust, Partition, War, Nakba

Both peoples experienced 1948 as existential. For Jews, it was survival after the Holocaust and the creation of a state. For Palestinians, it was catastrophe—the destruction of their society.

The civil war phase (November 1947-May 1948) saw Jewish forces gain the upper hand. The Deir Yassin massacre (April 9, 1948)—100+ villagers killed—spread terror. Haifa and Jaffa fell. Populations fled or were expelled.

On May 14, 1948, David Ben-Gurion declared Israeli independence. Arab armies invaded the next day. The war continued until 1949.

The Nakba: Scale and Mechanisms

700,000-750,000 Palestinians were displaced. 400-500 villages depopulated. ~80% of the Arab population in Israeli-controlled territory fled or was expelled.

“'Driving out' is a term with a harsh ring. Psychologically, this was one of the most difficult actions we undertook. The population of Lod did not leave willingly.”

— Yitzhak RabinFrom his memoirs, passage censored in 1979 and later restored

Historian Benny Morris's research shows: ~55% fled due to Jewish military operations, ~25% from fear and panic, ~15% from explicit expulsion orders. The claim that Arab leaders ordered the flight has been largely debunked.

By 1949: Israel controlled 78% of Mandate Palestine. Jordan held the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Egypt held Gaza. No peace treaties were signed—only armistices.

Critical finding: The Holocaust and the Nakba are not morally equivalent—6 million murdered is not the same as 700,000 displaced. But both are catastrophes that shape their peoples' consciousness. Understanding this requires holding multiple truths simultaneously.

UN Resolution 181 (1947)—the partition plan that Jews accepted and Arabs rejected.

United Nations · Public Domain

David Ben-Gurion reads the Declaration of Independence, May 14, 1948—Israel is born.

Government Press Office · Public Domain

Palestinian refugees fleeing during the Nakba—700,000 displaced, 400+ villages depopulated.

UNRWA Archives · Public Domain/UN

Borders Without Peace

New States, Refugees, Cold War

The Green Line created a temporary boundary that became permanent in fact but was never accepted as final by any party.

Israel absorbed mass immigration—700,000 Jews arrived 1948-1951, including Holocaust survivors from Europe and Mizrahi Jews expelled from Arab countries. Population doubled in three years.

150,000 Palestinians remained in Israel as citizens but under military administration until 1966. Land confiscation continued under the Absentee Property Law.

Palestinian refugees remained in camps in Gaza, West Bank, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan. UNRWA was established in 1949 to administer them. Israel refused return. Resolution 194 was ignored. The refugee issue remains unresolved.

The 1956 Suez Crisis saw Israel conquer Sinai, only to withdraw under US/USSR pressure. The 1964 PLO founding marked Palestinian nationalism taking organizational form.

By 1967, tensions escalated: water disputes, border incidents, fedayeen raids. Nasser closed the Straits of Tiran. War was coming.

Key finding: Armistice is not peace. Both sides prepared for the next war, which arrived in 1967.

The Green Line—comparing the UN partition plan (1947) with the 1949 armistice lines.

Wikimedia Commons · CC BY-SA

The Mandelbaum Gate (1953)—the only crossing point between Israeli and Jordanian Jerusalem.

Wikimedia Commons · Public Domain

Fawwar refugee camp, 1951—where Palestinians waited for a return that never came.

UNRWA Archives · Public Domain/UN

The Occupation

1967 to Oslo

The 1967 Six-Day War transformed the conflict. Israel captured the West Bank, Gaza, Sinai, and Golan Heights—tripling its controlled territory and placing millions of Palestinians under military occupation.

UN Resolution 242 called for “withdrawal from territories” (ambiguously: “the” territories vs. some territories) in exchange for peace. It remains the basis for all subsequent negotiations.

What was intended as “bargaining chips” became permanent. The first settlements appeared in 1967. By 1993, over 100,000 settlers lived in the West Bank and Gaza.

Life Under Occupation

Military administration. Permits required for movement, building, work. Land confiscation for settlements. Detention without trial. Economic restrictions. Collective punishment.

The 1973 Yom Kippur War led to the Camp David Accords (1978)—full peace with Egypt; Israel returned Sinai. But the Palestinian dimension was never resolved.

The First Intifada (1987-1993)—a popular uprising of strikes, boycotts, and stone-throwing—changed everything. ~1,100 Palestinians and ~160 Israelis died. It created the conditions for Oslo.

Key finding: Occupation intended as temporary became permanent. Settlements created “facts on the ground” that made withdrawal increasingly difficult.

Rabbi Shlomo Goren blows the shofar at the Western Wall, June 1967—Israel captures all of Jerusalem.

Israeli Government Press Office · Public Domain

An Israeli settlement in the West Bank—what began as 'bargaining chips' became permanent facts on the ground.

Wikimedia Commons · CC BY-SA

The First Intifada (1987-1993)—a popular uprising that changed the terms of the conflict.

Wikimedia Commons · Various

Oslo's Promise and Collapse

From Handshake to Intifada to Split

The Oslo Accords (1993) raised hopes for a two-state solution. The Palestinian Authority was established; Israel and PLO recognized each other. But Oslo was a framework, not a final agreement.

The West Bank was divided: Area A (PA control), B (joint), C (Israeli control). Final status issues—Jerusalem, refugees, settlements, borders—were deferred. And settlements doubled during the “peace process.”

Rabin's assassination by an Israeli extremist (November 1995) removed the Israeli leader most committed to territorial compromise. Camp David II (2000) failed—blame contested by both sides.

The Second Intifada (2000-2005) was far deadlier than the first. Suicide bombings killed ~1,000 Israeli civilians. Israeli military operations killed ~3,000 Palestinians. Trust was destroyed.

Sharon's 2005 Gaza disengagement removed all Israeli settlements but left Gaza isolated—Israel retained control of borders, airspace, and coast. In 2006, Hamas won Palestinian elections. In 2007, Hamas and Fatah split: Hamas controlled Gaza; PA/Fatah controlled parts of the West Bank.

Key finding: Oslo created a Palestinian Authority but not a Palestinian state. The peace process failed to deliver peace. By 2007, the two-state solution was in critical condition.

The Oslo handshake, September 13, 1993—Rabin and Arafat, with Clinton watching. Hope at its height.

White House · Public Domain

Yitzhak Rabin—the Israeli general who sought peace, assassinated by an Israeli extremist in 1995.

Israeli GPO · Public Domain

The separation barrier—called a 'security fence' by Israel, an 'apartheid wall' by Palestinians.

B'Tselem/Wikimedia · CC BY-SA

The Present Crisis

Gaza Wars and Beyond

Since 2007, the conflict has been characterized by Gaza's isolation, periodic devastating wars, West Bank settlement expansion, and diplomatic stalemate.

Gaza under blockade became what the UN called “unlivable”—96% of water unfit to drink, 4-8 hours of electricity daily, 45% unemployment. Periodic wars (2008-09, 2012, 2014, 2021) caused massive destruction.

West Bank settlements expanded continuously—from 280,000 settlers in 2007 to 500,000+ by 2023 (plus 230,000 in East Jerusalem).

October 7, 2023 and Aftermath

On October 7, 2023, Hamas-led forces attacked southern Israel. ~1,200 people were killed—mostly civilians. ~240 hostages taken. It was the deadliest day for Jews since the Holocaust.

Israel's military response has caused unprecedented destruction in Gaza. As of December 2024: 40,000+ killed according to Gaza Health Ministry, 1.9 million displaced, 60%+ of buildings damaged or destroyed. The conflict continues.

International responses have included UN ceasefire calls (US vetoed multiple), an ICJ genocide case filed by South Africa (ongoing), and ICC arrest warrant applications for Israeli and Hamas leaders.

Note: This is an active conflict. Events are ongoing. Some claims require verification. The essay presents verified facts where available and documents uncertainty where it exists.

A girl walks through Gaza to get food, August 2024—the human cost of the ongoing conflict.

Jaber Jehad Badwan · CC BY-SA 4.0

Destruction in Gaza, October 2023—60% of buildings damaged or destroyed by December 2024.

Fars News Agency · CC BY 4.0

Palestinian territories as of 2024—fragmented, blockaded, under occupation.

Wikimedia Commons · CC0

Sources & Further Reading

This essay draws on sources from multiple scholarly traditions. Each source is labeled by its institutional origin for transparency. Contested claims are sourced from multiple traditions.

Primary Archives .gov

- Mandate for Palestine (1922)archive

- American Colony in Jerusalem Collectionarchive

- U.S. Recognition of Israel: Primary Documentsarchive

University Research Guides .edu

- Israel & Palestine: Historical Primary Sourcesacademic

- Palestinian Studies: Archives & Primary Sourcesacademic

- Middle East Primary Sources Guideacademic

- Readings and Digital Resources on Palestineacademic

Academic Books & Journals

- A History of Modern PalestineacademicIsraeli

- The Question of PalestineacademicPalestinian

- 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli WaracademicIsraeli

- The Ethnic Cleansing of PalestineacademicIsraeli

- Palestine: A Four Thousand Year HistoryacademicPalestinian

- The Bible UnearthedacademicIsraeli

- The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem RevisitedacademicIsraeli

- Palestinian IdentityacademicPalestinian

- The Iron CageacademicPalestinian

Institutional Reports & Human Rights Organizations

- UN Information System on the Question of PalestineinstitutionalInternational

- B'Tselem Human Rights ReportsinstitutionalIsraeli

- Institute for Palestine StudiesinstitutionalPalestinian

- Amnesty International ReportsinstitutionalInternational

- UN OCHA Reports on GazainstitutionalInternational

Image Credits

All images sourced from Wikimedia Commons with proper licensing. No fair use images.

- UN Partition Plan map 1947 — United NationsPublic Domain

- Israeli Declaration of Independence — Government Press OfficePublic Domain

- Palestinian refugees 1948 — UNRWA ArchivesPublic Domain/UN

- Levant region orthographic projection — NASA/Wikimedia CommonsPublic Domain

- View of Jerusalem from Augusta Victoria — Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA

- Jordan Rift Valley panorama — Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA 2.0

- Merneptah Stele in Cairo Museum — Egyptian Museum, CairoPublic Domain

- Aerial view of Tel Megiddo — Government Press Office of IsraelCC BY-SA 2.0

- Amarna Letter cuneiform tablet — British Museum/WikimediaPublic Domain

- Map of ancient Canaan — Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA

- Sea Peoples relief at Medinet Habu — Wikimedia CommonsPublic Domain

- Philistine bichrome pottery — Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA

- Arch of Titus Menorah relief — Wikimedia CommonsPublic Domain

- Bar Kokhba revolt coin — Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA

- Madaba mosaic map — St. George's Church, MadabaPublic Domain

- Dome of the Rock — Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA

- Al-Aqsa Mosque — David ShankboneCC BY-SA

- Historical depiction of Saladin — Wikimedia CommonsPublic Domain

- Panorama of Jerusalem 1870 — Frederick Whitmore HollandPublic Domain

- Jews at Western Wall 1870s — Felix BonfilsPublic Domain

- Four Holy Cities plaque — Wikimedia CommonsPublic Domain

- First Zionist Congress delegates 1897 — Wikimedia CommonsPublic Domain

- Theodor Herzl portrait — Wikimedia CommonsPublic Domain

- Jaffa from the orange groves — Library of CongressPublic Domain

- Balfour Declaration document — British National ArchivesPublic Domain

- General Allenby entering Jerusalem 1917 — Library of CongressPublic Domain

- Arab rebels 1936 Palestine revolt — Wikimedia CommonsPublic Domain

- 1949 Armistice lines comparison — Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA

- Mandelbaum Gate Jerusalem — Wikimedia CommonsPublic Domain

- Fawwar refugee camp 1951 — UNRWA ArchivesPublic Domain/UN

- Rabbi Goren at Western Wall 1967 — Israeli Government Press OfficePublic Domain

- Israeli settlement near Jericho — Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA

- First Intifada Gaza Strip — Wikimedia CommonsVarious

- Oslo Accords handshake 1993 — White HousePublic Domain

- Yitzhak Rabin portrait — Israeli GPOPublic Domain

- West Bank separation barrier — B'Tselem/WikimediaCC BY-SA

- Girl walking in Gaza during war — Jaber Jehad BadwanCC BY-SA 4.0

- Gaza destruction 2023 — Fars News AgencyCC BY 4.0

- Palestinian territories map 2024 — Wikimedia CommonsCC0