Human Evolution

Visualized

7 million years of our story—from the first upright steps in African woodlands to the genetic echoes of Neanderthals in your DNA.

Deep Time

If Earth's 4.5 billion year history were compressed into a single year, humans would appear in the final 4 seconds before midnight on December 31st.

To understand human evolution, we must first grapple with a concept our brains struggle to comprehend: deep time. The Earth is approximately 4.54 billion years old. Life appeared roughly 3.8 billion years ago. But our lineage—the —branched off from chimpanzees only about 6-7 million years ago.

If we compress Earth's entire history into a 12-hour clock starting at midnight, the first appear at approximately 11:59:07—less than a minute before noon. Modern humans, Homo sapiens, emerge in the final 20 minutes. And all of recorded human history—agriculture, cities, writing, empires—occupies just the last 31 seconds.

When you take a long, long view... the one thing about the long term perspective is that it lowers the blood pressure.

This perspective matters. It reminds us that the characteristics we consider quintessentially human—language, art, complex societies—are evolutionary novelties. For most of our lineage's existence, our ancestors lived very differently than we do.

How We Know

Every fossil tells a story—but reading that story requires multiple scientific disciplines working in concert.

The study of human evolution relies on multiple converging lines of evidence. No single fossil or gene tells the whole story. Instead, scientists piece together our past from fossilized bones, stone tools, ancient DNA, and comparative anatomy with living species.

Radiometric Dating

Measures the decay of radioactive isotopes in volcanic rocks surrounding fossils. Potassium-argon and argon-argon dating work for rocks millions of years old.

Provides absolute ages with known error ranges

Ancient DNA

Genetic material extracted from bones up to several hundred thousand years old. Has revealed interbreeding between human species.

Revolutionized our understanding since 2010

Stratigraphy

The study of rock layers and their sequence. Fossils in lower layers are generally older than those above.

Establishes relative chronology

Comparative Anatomy

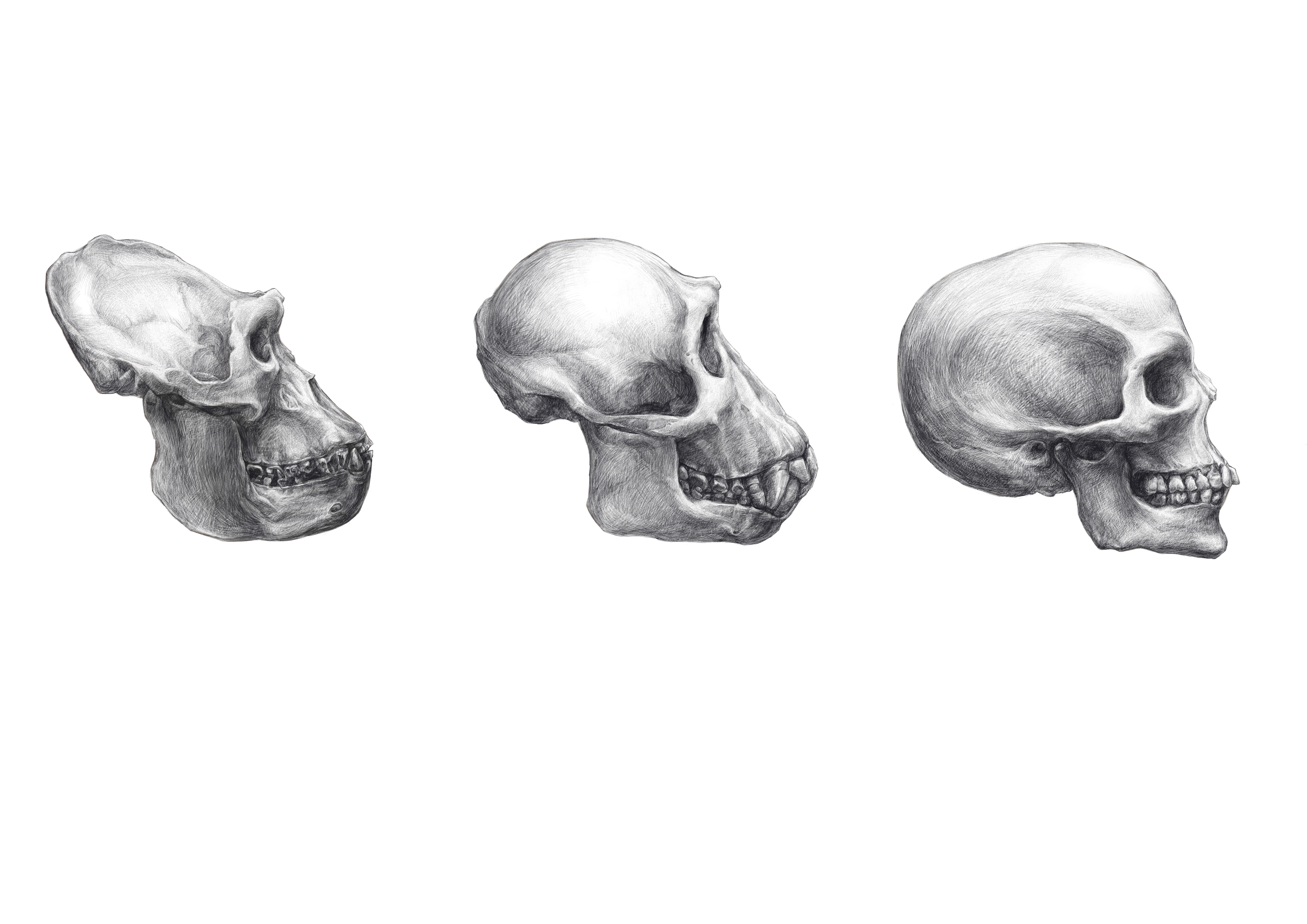

Comparing skeletal features with living apes and other fossils to understand evolutionary relationships and locomotion.

Reveals how our bodies changed over time

I used to say I was trying to improve our understanding of human evolution. Now I prefer to say I'm trying to reduce our ignorance about it.

The fossil record is inherently incomplete. Fossilization requires specific conditions, and most organisms decompose without leaving traces. What we have discovered represents a tiny fraction of the individuals who ever lived. Yet despite these limitations, the evidence consistently points to Africa as the birthplace of our lineage.

Tree of Life

We share 98.8% of our DNA with chimpanzees. That 1.2% difference—accumulated over 6-7 million years—is what makes us human.

Humans belong to the great ape family (), which includes chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans. Within this family, we share our closest relationship with chimpanzees and bonobos—we diverged from their ancestors approximately 6-7 million years ago.

But this doesn't mean we "evolved from chimps." Modern chimpanzees and modern humans are cousins, not ancestors and descendants. Both lineages have been evolving for the same amount of time since our split. The common ancestor we shared would have looked different from either species today.

What makes human evolution particularly interesting is that for most of our history, multiple hominin species coexisted. The idea of a single "missing link" is fundamentally flawed—evolution produced a "bushy" tree with many branches, not a simple chain.

Species Through Time

The straight line has blossomed into a spreading, rather uncontrolled bush.

African Origins

The East African Rift Valley—a geological scar running through the continent—preserved the evidence of our earliest ancestors in its sediments.

The earliest known hominins come from Africa. The Great Rift Valley—a massive geological feature running from Ethiopia to Mozambique—has been particularly productive for fossil discoveries. The rifting process exposed ancient sediments and created conditions that preserved bones for millions of years.

Sahelanthropus tchadensis

'Toumai'

~7-6 MaThe oldest candidate hominin, found in Chad. Its forward-positioned foramen magnum suggests possible bipedalism.

May represent the earliest known hominin

Ardipithecus ramidus

'Ardi'

4.4 MaA 45% complete skeleton from Ethiopia showing a mosaic of ape-like and hominin features. Had a grasping big toe but walked bipedally.

Demonstrates woodland bipedalism

Australopithecus afarensis

'Lucy'

3.2 MaThe famous partial skeleton from Hadar, Ethiopia. About 40% complete, representing a young adult female.

Best-known early hominin

The message we would like to convey is that our species is much older than we thought and that it did not emerge in an Adamic way in a small 'Garden of Eden' somewhere in East Africa. It is a pan-African process and more complex scenario than what has been envisioned so far.

The represent a diverse radiation of early hominins. They had small brains (roughly the size of a chimpanzee's), but their lower bodies were adapted for walking upright. This combination—bipedal locomotion with small brains—challenges the old assumption that brain expansion drove human evolution.

Walking Upright

The footprints at Laetoli, frozen in volcanic ash 3.66 million years ago, show creatures walking upright—before brain expansion, before stone tools.

—walking upright on two legs—is the defining characteristic of hominins. It appeared millions of years before large brains, complex tools, or language. The footprints at , Tanzania, preserved in volcanic ash 3.66 million years ago, provide direct evidence of this early walking.

Laetoli Footprints

3.66 MaA trackway of footprints made by at least two individuals walking through fresh volcanic ash. The prints show a human-like gait with a heel strike and toe push-off.

Oldest direct evidence of bipedal locomotion

The skeleton underwent significant modifications for upright walking. The shifted from the back of the skull to underneath it, allowing the head to balance atop the spine. The pelvis became shorter and bowl-shaped to support internal organs. The spine developed an S-curve for shock absorption.

Why did bipedalism evolve? Scientists have proposed many hypotheses: freeing the hands for carrying food or tools, seeing over tall grass, thermoregulation in open environments, or simply being an efficient way to travel between food patches. The truth likely involves multiple factors—evolution rarely has single causes.

Genus Homo

When the first stone tools were struck 3.3 million years ago, something unprecedented had begun—technology as a survival strategy.

The genus Homo emerged around 2.5 million years ago, marked by increased brain size and a new relationship with technology. Homo habilis, the "handy man," is associated with the earliest stone tools—simple flakes struck from river cobbles.

Oldowan Tools

2.6 MaSimple choppers and flakes made by striking one rock against another. Used for processing meat and plant foods.

Earliest systematic tool tradition

Acheulean Handaxes

1.76 MaTeardrop-shaped bifacial tools requiring sophisticated planning and skill. Remarkably consistent across continents and millennia.

Shows advanced cognitive planning

Turkana Boy

KNM-WT 15000

1.6 MaA nearly complete Homo ergaster skeleton of an adolescent boy. Shows modern human body proportions with a tall, lean build.

First evidence of modern body plan

was the first hominin to leave Africa. By 1.8 million years ago, populations had reached Georgia (at the site of Dmanisi) and eventually spread across Asia. This species survived for nearly 2 million years—far longer than our own species has existed.

Brain Size Through Evolution

Brain sizes shown are species averages. Significant individual variation existed within each species.

Fifty years ago, we really could have put most of our evidence on a small card table. Now this stage couldn't hold it all. There are thousands of fossils.

Other Humans

For most of our evolutionary history, we were not alone. Multiple human species walked the Earth simultaneously.

Perhaps the most humbling discovery of modern paleoanthropology is that Homo sapienswas never alone. For most of our species' existence, we shared the planet with other human species—some of whom we met, lived alongside, and even had children with.

Homo neanderthalensis

Neanderthals

400-40 kaOur closest extinct relatives, living in Europe and western Asia. They had larger brains than us, made sophisticated tools, buried their dead, and created art.

1-2% of non-African DNA is Neanderthal

Denisovans

~300-30 kaKnown primarily from DNA extracted from bone fragments found in Siberia. They ranged across Asia and interbred with both Neanderthals and modern humans.

Up to 6% of Melanesian DNA is Denisovan

Homo floresiensis

'Hobbit'

190-50 kaA small-bodied, small-brained human species from the island of Flores, Indonesia. Adults stood only about 1 meter tall.

Survived until ~50,000 years ago

Homo naledi

335-236 kaDiscovered in South Africa's Rising Star Cave system. Combined primitive body features with human-like hands and feet. May have deliberately disposed of their dead.

Contemporary with early H. sapiens

We used to think that when modern humans left Africa, they entered a Europe populated only by Neanderthals. But the genetic evidence tells us there were multiple populations, multiple migrations, and multiple mixings.

The discovery of —genetic mixing between species—has transformed our understanding. weren't simply replaced; they were partially absorbed into our gene pool. Their DNA persists in billions of people today, influencing everything from immune function to skin pigmentation.

Archaic DNA in Modern Populations

Note: Percentages are approximate averages. Individual variation exists within all populations. Source: Compiled from Green et al. 2010, Reich et al. 2010, Sankararaman et al. 2014

Homo Sapiens

In a cave in Morocco, 315,000 years ago, people who looked remarkably like us were shaping stone tools and burying their dead.

In 2017, a team of researchers announced a discovery that pushed back the origin of our species by over 100,000 years. At , Morocco, they found fossils of early Homo sapiens dating to approximately 315,000 years ago—making them the oldest known members of our species.

Jebel Irhoud

315 kaA cave site in Morocco where at least five individuals were found, along with stone tools and animal bones. The skulls show modern human faces but more elongated braincases.

Oldest known Homo sapiens fossils

What defines Homo sapiens? Anatomically, we have a distinctive suite of features: a high, rounded cranium; a flat, vertical forehead; a small, retracted face tucked under the braincase; and a chin—a feature unique among hominins. But these traits didn't appear all at once. The Jebel Irhoud fossils show that our species' emergence was gradual, with different features evolving at different times.

There is no 'Garden of Eden' in Africa, or elsewhere, where our species first arose. Instead, Homo sapiens evolved as an interconnected population spread across Africa.

Omo Kibish

~233 kaTwo partial skulls from Ethiopia. Omo I shows more modern features; Omo II is more archaic. Found in the same deposits, they illustrate the variation among early H. sapiens.

Among the oldest in East Africa

Herto Skulls

160 kaThree skulls from the Middle Awash, Ethiopia. Nearly complete, they show clear H. sapiens anatomy and evidence of mortuary practices—skulls were defleshed and polished.

Evidence of early ritual behavior

Migrations

Between 70,000 and 50,000 years ago, a small group of humans left Africa. Their descendants would eventually populate every continent.

The dispersal represents one of the most consequential events in human history. While earlier migrations (such as those that brought Homo erectus to Asia 1.8 million years ago) were significant, the movement of Homo sapiens would eventually lead to the colonization of every continent except Antarctica.

Genetic evidence suggests a major dispersal between 70,000 and 50,000 years ago. A relatively small founding population—perhaps just a few thousand individuals—crossed from Africa into the Arabian Peninsula and beyond. From this population descended all non-African peoples alive today.

Skhul and Qafzeh

~120-90 kaCaves in Israel with early modern human remains, representing an earlier migration out of Africa that may not have contributed significantly to later populations.

Evidence of early failed dispersal

Niah Cave, Borneo

~45 kaDeep skull fragments represent some of the earliest modern humans in Southeast Asia, showing rapid dispersal along the southern route.

Early Southeast Asian presence

Lake Mungo, Australia

~42-45 kaSkeletal remains and cremation from Australia, indicating humans crossed the Wallace Line (requiring sea voyages) very early.

Earliest evidence in Australia

The peopling of the Americas was the final chapter in the long story of human migration, but it was far more complex than a single wave of pioneers crossing an ice-free corridor.

As modern humans spread across the globe, they encountered other human species. In Europe and western Asia, they met . In Asia, they encountered and possibly other archaic groups. These meetings weren't always peaceful, but they weren't always violent either—the genetic evidence proves that interbreeding occurred.

Culture & Cognition

The same 32 geometric symbols appear in caves across Europe over 30,000 years. This was not the start-up phase of a new invention.

What makes humans human? Beyond anatomy, we are distinguished by our capacity for symbolic thought, complex language, cumulative culture, and the ability to imagine things that don't exist. When did these abilities emerge?

For decades, researchers spoke of a "Human Revolution" occurring around 50,000 years ago in Europe, marked by an explosion of art, ornaments, and complex tools. But discoveries in Africa have overturned this narrative. Symbolic behavior appears much earlier—and Homo sapiens isn't the only species that showed it.

Blombos Cave Engravings

77 kaOchre blocks with geometric patterns from South Africa—crosshatched designs that represent some of the earliest known abstract art.

Earliest known deliberate abstract marking

Nassarius Shell Beads

82 kaPerforated shells from Grotte des Pigeons, Morocco, that were strung as beads. Microscopic analysis confirms they were worn, not just collected.

Evidence of personal ornamentation

Levallois Technique

~400 kaA sophisticated method of preparing stone cores to produce flakes of predetermined shape. Required mental planning and teaching.

Evidence of advanced cognition

The geometric signs we find in caves across Europe appear in the same forms for over 30,000 years. That's not the start-up phase of a new invention—it's a system that was already in place.

, too, showed signs of symbolic behavior. They made jewelry from eagle talons, created pigments from manganese dioxide, and may have produced cave art. The boundary between "us" and "them" becomes increasingly blurry the more we learn.

Present & Future

You carry within your DNA fragments of Neanderthals, perhaps Denisovans, and countless ancestors stretching back millions of years.

The story of human evolution is not over. We are living it. Every person alive today carries a genetic archive stretching back millions of years—including fragments from species we thought were long gone.

Modern genetic technology has revealed that most people outside Africa carry approximately 1-2% DNA. Melanesians and some other populations carry an additional 3-6% DNA. These aren't just curiosities—they've had real effects. Denisovan genes help Tibetans live at high altitude. Neanderthal genes influence our immune systems and may affect susceptibility to certain diseases.

As a species, humans are remarkably similar genetically, reflecting our recent common ancestry from Africa within the past 100,000 years. We are all Africans.

EPAS1 Gene

Tibetans carry a variant of this gene that helps with high-altitude adaptation. Analysis revealed it came from Denisovans—an example of adaptive introgression.

Archaic genes still helping us today

HLA Genes

Genes critical to immune function. Studies show that some Neanderthal and Denisovan variants were beneficial and were rapidly selected for in modern human populations.

Ancient immune adaptations

Is human evolution still occurring? In the biological sense, yes—but slowly, and shaped increasingly by culture and technology. Medicine allows survival of individuals who might not have survived in the past. Travel connects gene pools that were once isolated. The selective pressures that shaped our ancestors have largely changed.

Yet the fundamental lesson of human evolution remains: we are part of nature, not separate from it. We are the products of the same processes that shaped every other species on Earth—mutation, selection, drift, and the contingency of historical accident. Understanding our past helps us understand ourselves.

We have this extraordinary view now of our past, through genetics and fossils, that shows us we're part of a vast experiment in what it means to be human.

Glossary

Sources & Further Reading

Key Books

- Stringer, C. & Andrews, P. (2012). The Complete World of Human Evolution. Thames & Hudson.

- Reich, D. (2018). Who We Are and How We Got Here. Pantheon Books.

- Pääbo, S. (2014). Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes. Basic Books.

- Johanson, D. & Edgar, B. (2006). From Lucy to Language. Simon & Schuster.

- Wood, B. (2019). Human Evolution: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Academic Journals

- Nature (www.nature.com) - Primary source for major fossil and genetic discoveries

- Science (www.science.org) - Major research publications on human evolution

- Journal of Human Evolution - Specialized peer-reviewed research

- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - Interdisciplinary human evolution research

Research Institutions

- Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History - Human Origins Program

- Natural History Museum, London - Human Evolution collection

- Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

- The Leakey Foundation