Anything that flies on anything that moves.

— Henry Kissinger, December 9, 1970

Cambodia Bombed

(1965–1973)

The Air War You Weren't Meant to See — Visualized

Before the Storm

Cambodia, officially neutral under Prince Norodom Sihanouk, found itself caught between superpowers. While maintaining public neutrality, Sihanouk tacitly permitted Vietnamese communist sanctuaries along the eastern border and allowed the Sihanouk Trail—a supply route that moved an estimated 21,000 tons of material through the port of Sihanoukville.

The United States began probing Cambodia's borders as early as 1965. Project Daniel Boone (later Salem House) sent covert reconnaissance teams across the border beginning in May 1967. Between 1965 and 1968, U.S. aircraft flew 2,565 sorties into Cambodian airspace, dropping 214 tons of ordnance—small-scale tactical strikes that foreshadowed what would come.

Military planners fixated on COSVN—the Central Office for South Vietnam—believing it to be a hidden Pentagon from which the Vietnamese communists directed the war. In reality, COSVN was a dispersed network of mobile command posts, not a fixed target. This phantom would justify years of bombing.

Norodom Sihanouk

Prince and Head of State (until March 1970)

- Maintained Cambodia's official neutrality during the Vietnam War

- Tacitly permitted Vietnamese communist sanctuaries in border regions

- Enabled Sihanouk Trail supply route through Cambodian territory

- Overthrown by Lon Nol coup in March 1970

CIA map showing the Cambodian-Vietnamese border region and infiltration routes (1970) — Library of Congress, Public Domain

“The ball game is over.”— Mission Completion Code, March 18, 1969

Operation Breakfast

On February 9, 1969, General Creighton Abrams sent a cable to Washington proposing B-52 strikes on suspected COSVN headquarters in Base Area 353—the "Fishhook" region of Cambodia. The proposal reached the new president within days.

Nixon authorized the strike on March 15, 1969, at 3:35 PM. He demanded absolute secrecy. Henry Kissinger and Colonel Alexander Haig met with Colonel Ray Sitton—the JCS B-52 expert known as "Mr. B-52"—to design a dual reporting system that would hide the bombing from Congress, the press, and even the Secretary of State.

On March 18, between 48 and 60 B-52 Stratofortress bombers struck Base Area 353. The official records showed the bombs fell in South Vietnam. The real coordinates were transmitted through back channels, then destroyed. This was Operation Breakfast—the first course in what would become Operation Menu.

Military assessments found "The City"—a logistics complex containing 182 bunkers and 1,282 weapons. But COSVN headquarters was never destroyed. The phantom proved to be just that.

Richard Nixon

37th President of the United States

- Authorized Operation Menu (March 1969)

- Demanded absolute secrecy to avoid Congressional reaction

- Announced Cambodia "incursion" on April 30, 1970

- Escalated bombing under Operation Freedom Deal

“If the world's most powerful nation acts like a pitiful helpless giant, the forces of totalitarianism and anarchy will threaten free nations throughout the world.”— Cambodia Incursion Address, April 30, 1970

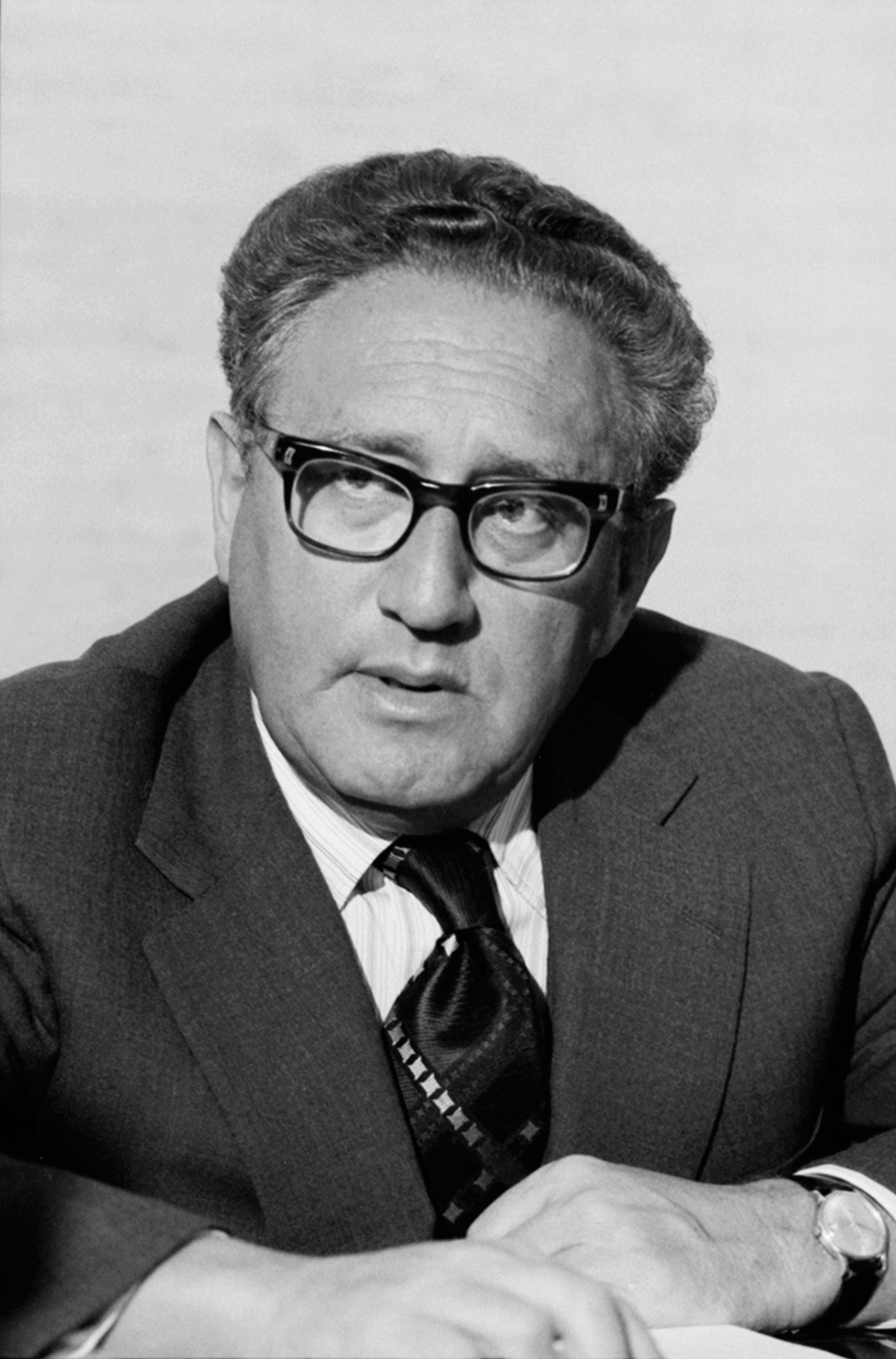

Henry Kissinger

National Security Adviser (1969-1975)

- Designed dual reporting system with Colonel Sitton

- Personally selected bombing targets

- Ordered FBI wiretaps after Beecher leak

- Issued "anything that flies on anything that moves" order

“Anything that flies on anything that moves.”— Phone conversation with Alexander Haig, December 9, 1970

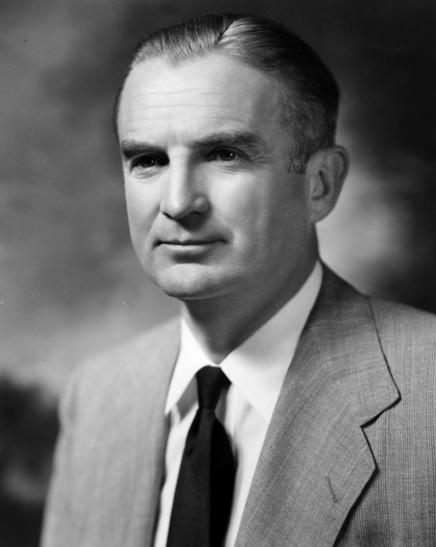

General Creighton Abrams

MACV Commander

- Proposed B-52 strikes on COSVN (February 1969)

- Claimed targeted areas were "underpopulated"

- Later testified about "special furnace" for record destruction

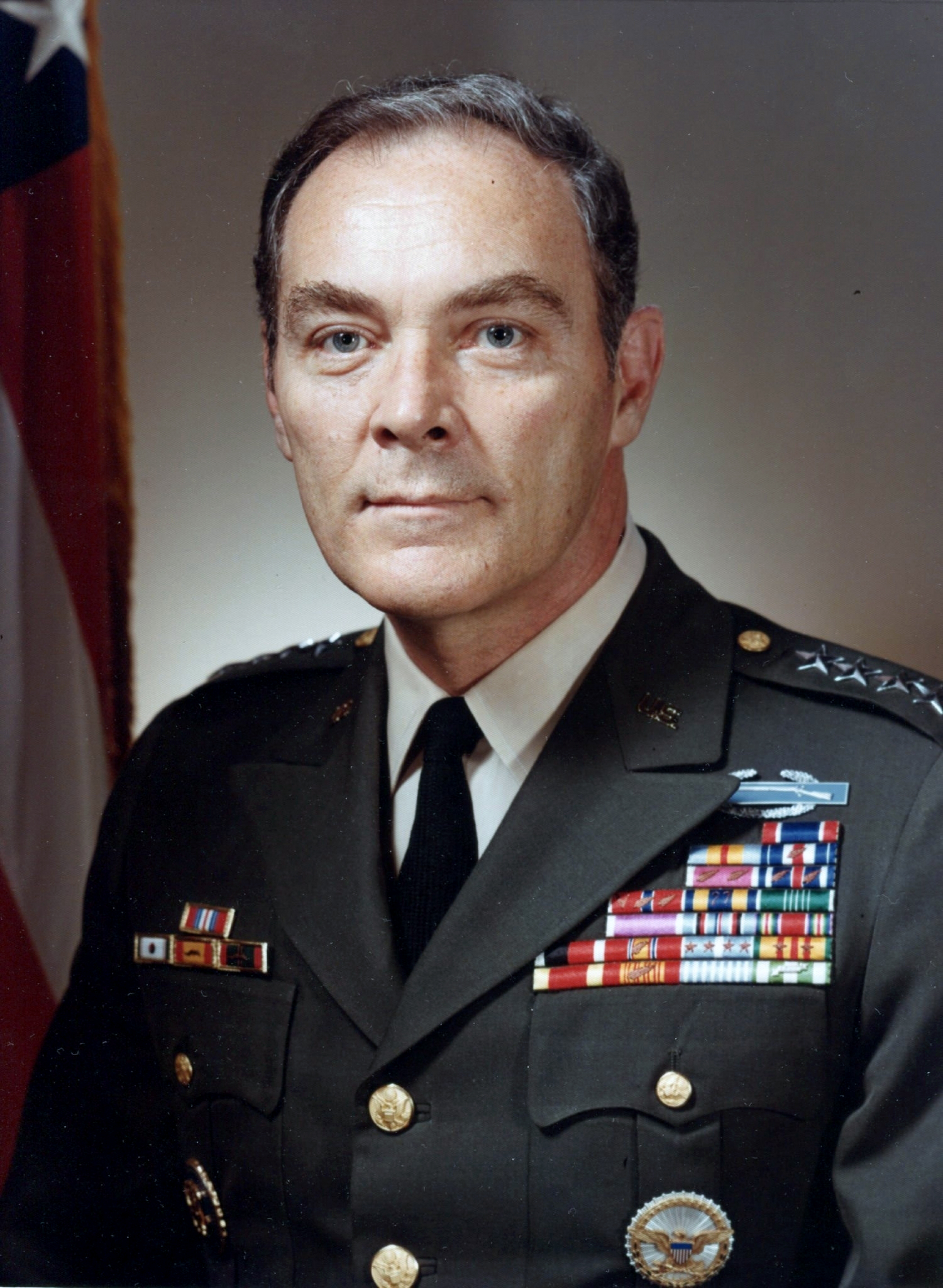

General Earle Wheeler

Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff

- First proposed bombing Cambodian sanctuaries (January 30, 1969)

- One of few with full knowledge of dual reporting system

- Coordinated military targeting with White House

Melvin Laird

Secretary of Defense (1969-1973)

- Opposed secrecy (not the bombing itself)

- Warned Nixon that secrecy was unsustainable

- Advocated for congressional notification

“I was all for hitting those targets in Cambodia, but I wanted it public.”

B-52D Stratofortress releasing bombs during an Arc Light mission over Southeast Asia — U.S. Air Force, Public Domain

The Leak

On May 9, 1969, William Beecher of the New York Times published an article headlined "Raids in Cambodia by U.S. Unprotested." The story ran on the front page, lower right. It should have been a scandal. Instead, it barely registered.

Kissinger's reaction was fury. He called FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover: "We will destroy whoever did this." Within days, the FBI began wiretapping seventeen government officials and journalists—searching for the source of the leak.

Morton Halperin, an NSC staffer and Beecher's college roommate, was the prime suspect. His phone was tapped for twenty-one months. The wiretaps found nothing about Cambodia but captured private conversations—fuel for later lawsuits against Kissinger.

Why didn't the story catch fire? The Pentagon's assessment: "Little adverse public reaction noted." Cambodia was officially neutral. The bombing was denied. The American public, already exhausted by Vietnam, didn't connect the dots. The secret held.

William Beecher

New York Times Military Correspondent

- Broke story of secret bombing (May 9, 1969)

- Article headline: "Raids in Cambodia by U.S. Unprotested"

- Triggered Kissinger's wiretap program

Morton Halperin

NSC Staffer

- Prime suspect as Beecher's source (was his college roommate)

- Phone tapped for 21 months

- Later sued Kissinger over illegal surveillance

J. Edgar Hoover

FBI Director

- Received Kissinger's call demanding investigation

- Authorized wiretaps on 17 officials and journalists

- FBI surveillance found no Cambodia leak evidence

Freedom Deal

On March 18, 1970, while Sihanouk was abroad, General Lon Nol seized power in a coup. The delicate fiction of Cambodian neutrality collapsed. Six weeks later, Nixon went on television.

"This is not an invasion of Cambodia," the President declared on April 30, 1970. U.S. ground forces crossed the border. Four students died at Kent State protesting the incursion. The bombing, no longer secret, now expanded.

Operation Freedom Deal replaced Operation Menu. The targeting zone grew from a 48-kilometer band along the border to half the country. In the final year alone, the U.S. dropped approximately 250,000 tons—half the campaign's total.

On December 9, 1970, Kissinger issued an order captured in a phone transcript with Alexander Haig: "Anything that flies on anything that moves." Haig laughed. The order became policy.

Lon Nol

General, later President (1970-1975)

- Led coup against Sihanouk (March 18, 1970)

- Established Khmer Republic with U.S. backing

- Received U.S. air support against Khmer Rouge

- Fled Cambodia April 1, 1975

The Kent State Four

Students killed May 4, 1970

- Allison Krause (19) — placed flower in Guard rifle barrel day before

- Jeffrey Miller (20) — subject of Pulitzer-winning photograph

- Sandra Lee Scheuer (20) — walking to class, not protesting

- William Schroeder (19) — ROTC student, walking between classes

“"What if you knew her and found her dead on the ground?" — Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, "Ohio"”

Ohio National Guard on campus at Kent State University during protests against the Cambodia incursion, May 4, 1970 — Public Domain

“Probably 12 hours a day.”— Major Hal Knight on document destruction

The Furnace

In December 1972, Major Hal Knight wrote to Senator William Proxmire. He had carried the secret for three years. Now he told everything: the fake coordinates, the burned records, the special furnace that ran "probably 12 hours a day."

On July 16, 1973, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger admitted to Congress that the bombing had been secret. Knight testified. The furnace had destroyed thousands of documents—but enough survived.

Senator Stuart Symington's investigation concluded the administration had "lied to Congress." Representative Robert Drinan introduced the first impeachment resolution against Nixon, citing "the totally secret air war in Cambodia for 14 months."

But Watergate consumed the oxygen. Cambodia became Article I of the impeachment inquiry—then was dropped from the final articles. The Case-Church Amendment passed, forcing an end to bombing. On August 15, 1973, the last American bombs fell on Cambodia.

Senator Stuart Symington

Armed Services Committee Member

- Led 1973 investigation into secret bombing

- Concluded administration "lied to Congress"

Representative Robert Drinan

First to Propose Nixon Impeachment

- Introduced impeachment resolution (July 31, 1973)

- Cited "the totally secret air war in Cambodia"

“How can we impeach the President for concealing a burglary but not for concealing a massive bombing?”— Congressional Record, 1973

Senator J. William Fulbright

Chairman, Foreign Relations Committee

- Longest-serving chair of Foreign Relations (1959-1974)

- Dual reporting system specifically designed to deceive his committee

- Led televised Vietnam War hearings

“Does the President assert—as kings of old—that as Commander in Chief he can order American forces anywhere for any purpose that suits him?”

Senator Frank Church

Co-author, Case-Church Amendment

- Co-authored Cooper-Church (1970) restricting Cambodia operations

- Co-authored Case-Church (1973) ending combat operations

- Later chaired Church Committee on intelligence abuses

Senator Thomas Eagleton

Sponsor, Eagleton Amendment

- Sponsored amendment to cut bombing funds (1973)

- Forced August 15, 1973 deadline for end of operations

- Key figure in congressional pushback against executive war powers

The Data War

In 2000, President Clinton declassified U.S. Air Force bombing records during a visit to Vietnam. Researchers finally had data. Yale scholars Ben Kiernan and Taylor Owen analyzed the records, publishing their findings in 2006.

Their initial claim: 2.7 million tons—more than all bombs dropped on Germany in World War II. The number entered public discourse, repeated in documentaries and scholarship. It became the defining statistic of the Cambodia bombing.

But the number was wrong. Holly High and other researchers discovered a systematic error in the SEADAB database. The "Load Weight" field had been corrupted—multiplied by 10. Subsequent analysis corrected the figure dramatically.

Owen and Kiernan publicly acknowledged the error. The corrected consensus: approximately 500,000 tons—still more than all bombs dropped on Japan in World War II, still devastating, but not the apocalyptic figure originally claimed. This essay uses the corrected number.

The widely-cited 2.7 million ton figure was publicly retracted by its original authors in 2015 after database errors were discovered.

Source: Kiernan & Owen, The Asia-Pacific Journal (2015)

Ben Kiernan

Yale Historian

- Founded Cambodian Genocide Program at Yale

- Co-authored "Bombs Over Cambodia" (2006)

- Later publicly corrected tonnage estimate

Taylor Owen

McGill Scholar

- Obtained and analyzed declassified USAF data

- Co-authored influential 2006 analysis

- Publicly acknowledged database error and correction

Holly High

University of Sydney Researcher

- Identified systematic errors in SEADAB tonnage data

- Led re-analysis of bombing database records

- Published critical correction in Journal of Vietnamese Studies (2013)

The Unintended Consequence

The Khmer Rouge numbered perhaps 1,000 fighters in 1969. By 1973, they fielded an estimated 220,000. Something had changed—and historians debate what role the bombing played.

A May 1973 CIA assessment noted that the Khmer Rouge used the bombing as "the main theme of their propaganda." A GAO report found that 60% of refugees cited bombing as their reason for displacement. Survivor testimony describes joining the resistance after raids destroyed villages.

The causal chain is debated. Ben Kiernan argues the bombing was decisive. Others point to Sihanouk's overthrow and subsequent endorsement of the Khmer Rouge, North Vietnamese support, pre-existing communist organization, and economic collapse from the civil war.

What is undeniable: the bombing destabilized Cambodia, displaced millions, and created conditions the Khmer Rouge exploited. On April 17, 1975—five years after the first acknowledged bombs fell—the Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh. What followed was genocide.

Pol Pot (Saloth Sar)

Khmer Rouge Leader

- Led communist insurgency during bombing period

- Exploited bombing devastation for recruitment

- Seized power April 17, 1975

- Oversaw genocide that killed 1.7-2 million

The Reckoning That Wasn't

The War Powers Resolution of 1973 emerged directly from the Cambodia bombing—an attempt to constrain future presidents from waging war without congressional approval. It remains the most concrete legislative legacy of the secret campaign.

Drinan's impeachment article citing Cambodia was rejected 26-12 by the House Judiciary Committee. Watergate prevailed. Nixon resigned over a break-in, not a bombing.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington bears 58,215 American names. Cambodia's memorials commemorate the Khmer Rouge genocide—Tuol Sleng, Choeung Ek, the killing fields. There is no comparable memorial for the bombing's Cambodian victims.

No formal U.S. apology has been issued. No reparations have been paid. The bombing exists in a strange commemorative vacuum—acknowledged in scholarship, largely absent from public memory.

Representative Elizabeth Holtzman

Congresswoman (D-NY)

- Filed lawsuit to stop Cambodia bombing in federal court

- Won initial injunction from Judge Judd (July 25, 1973)

- Supreme Court vacated the injunction six hours later

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. bears 58,215 American names. No comparable memorial exists for Cambodian bombing victims. — Hu Totya, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh—a former high school converted to a Khmer Rouge interrogation center. Cambodia's memorials commemorate the genocide, not the bombing that preceded it. — Adam63, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The memorial stupa at Choeung Ek, one of the "Killing Fields," holds the skulls of genocide victims. The bombing's role in destabilizing Cambodia remains debated but documented. — CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Still Unfinished

The bombing ended on August 15, 1973. The dying continued. Unexploded ordnance—bombs, cluster munitions, artillery shells—remained scattered across Cambodian soil. They are still being found.

Since 1979, unexploded ordnance has killed or injured over 65,000 Cambodians. The casualty rate has dropped dramatically—from 4,320 in 1996 to 49 in 2024—but approximately one person is still killed or injured every week.

Today, 1,856 square kilometers of Cambodia remain contaminated. Cambodia created a unique Sustainable Development Goal—SDG 18—specifically for mine action. Organizations like CMAC, HALO Trust, MAG, and APOPO work to clear the soil.

The original goal was a mine-free Cambodia by 2025. That deadline has been revised to 2030. The work continues. The war you weren't meant to see is still being cleaned up, bomb by bomb, field by field, life by life.

CMAC Deminers

Cambodian Mine Action Centre

- 596,168 mines destroyed since 1992

- 2,537,335 explosive remnants of war (ERW) cleared

- National organization leading clearance efforts

APOPO HeroRATs

Mine Detection Animals

- African Giant Pouched Rats trained to detect explosives

- Clear a tennis court-sized area in 20 minutes (vs. 4 days for humans)

- Too light to trigger mines—perfect for detection work

- Belgian NGO operates in Cambodia since 2015

A BLU-26 cluster bomblet—one of millions dropped on Cambodia. These submunitions scatter across wide areas and often fail to detonate, becoming deadly UXO. — Seabifar, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

APOPO trains African Giant Pouched Rats to detect explosives. A single rat can clear a tennis court-sized area in 20 minutes—a task that takes humans up to 4 days. — Mx. Granger, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Glossary

Sources & Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969-1976, Volume VI: Vietnam, January 1969 – July 1970

- National Security Archive, Kissinger Telcons Collection

- Nixon Presidential Library, NSC Files

- Congressional Record, 93rd Congress

- Senate Armed Services Committee, "Bombing in Cambodia" Hearings (1973)

- USAF Historical Research Agency Records

- CIA FOIA Electronic Reading Room

Academic Sources

- Kiernan, Ben. "The American Bombardment of Kampuchea, 1969-1973." Vietnam Generation (1989)

- Owen, Taylor and Ben Kiernan. "Bombs Over Cambodia." The Walrus (2006)

- Kiernan, Ben and Taylor Owen. "Making More Enemies than We Kill?" The Asia-Pacific Journal (2015)

- High, Holly, et al. "Electronic Records of the Air War Over Southeast Asia." Journal of Vietnamese Studies (2013)

- Shawcross, William. Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon, and the Destruction of Cambodia. Simon & Schuster (1979, 2002)

- Kiernan, Ben. How Pol Pot Came to Power. Yale University Press (1985, 2004)

- Kiernan, Ben. The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia. Yale University Press (1996, 2008)

- Chandler, David P. The Tragedy of Cambodian History. Yale University Press (1991)

- Clymer, Kenton. The United States and Cambodia, 1969-2000. Routledge (2004)