SLANG — The Word That Named the Unnameable

A 270-Year Journey from London's Criminal Underworld to TikTok

SLANG

The Word That Named the Unnameable

The Spark

What “Slang” Feels Like

You know slang when you hear it. It carries a charge—of belonging, of rebellion, of in-group knowledge. It's the vocabulary that doesn't appear in school books but fills every schoolyard.

Slang is not dialect (regional speech), jargon (professional vocabulary), or profanity (though it often overlaps). Slang is specifically vocabulary that marks social identity and currency—words that say “I belong here” as much as they mean anything at all.

But here's the question: where did the word “slang” itself come from? To name something is to have power over it. Who first named this phenomenon—and what were they trying to contain?

Birth Certificate

First Sightings in Print

“Thomas Throw had been upon the town, knew the slang well; had often sate a flasher at M——d——g——n's, and understood every word in the scoundrel's dictionary.”

—William Toldervy, The History of Two Orphans, 1756

The year 1756 marks the earliest confirmed written use of “slang” as a noun. Toldervy's novel describes a character who “knew the slang well”—meaning he understood the criminal vocabulary, the secret language of the London underworld.

But words live in speech long before they appear in print. Fifteen years earlier, in 1741, an account of the pickpocket Mary Young (alias Jenny Diver) at Tyburn execution used slang as a verb: “slanging the gentry mort rumly with a sham kinchin”—describing an elaborate deception scheme.

The word was already in circulation, already useful, already marking the boundary between those who belonged and those who did not.

The Mystery

Where the Word Came From

Here is the paradox at the heart of this etymology: the word “slang”—which names vocabulary of marginal, obscure, uncertain origin—is itself of marginal, obscure, uncertain origin.

From Norwegian "slengja" (to sling) or "slengjenamn" (nickname)

Leading hypothesisConnected to Romani vocabulary through criminal cant networks

SpeculativeSelf-referential term invented within underworld communities

SpeculativeFolk etymology combining "sling" and "language"

UnlikelyIn 2016, etymologist Anatoly Liberman declared confidently that the origin “is known.” The OED, reviewing the same evidence, politely disagreed. The mystery endures.

The word performs what it names: it arrived from the margins, its papers never quite in order, and it has never fully disclosed its origins.

America's Timeline

From Cant to Cool

“Slang in its origin is nearly always respectable; it is devised not by the stupid populace, but by individuals of wit and ingenuity.”

— H.L. Mencken, The American Language, 1919

Global Spread

English Slang Around the World

English slang has diversified across continents. Australian English coined arvo (afternoon), brekkie (breakfast), and servo (service station). British slang gave us cheeky, knackered, and gobsmacked. South African English blends Afrikaans (lekker) with local innovation.

The same word can mean entirely different things: American “pants” vs. British “pants” (trousers vs. underwear). What's casual in one dialect can be shocking in another.

Gatekeepers & Champions

Who Documented Slang

For centuries, “proper” lexicographers ignored slang or condemned it. The people who documented it were rebels themselves—antiquaries, journalists, poets, and linguists who believed everyday speech deserved scholarly attention.

Francis Grose

Published "A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue" (1785), deliberately parodying Samuel Johnson's august Dictionary by applying the same scholarly methods to disreputable vocabulary.

“SLANG: Cant language.”

John Camden Hotten

Published "The Slang Dictionary" (1859), the first attempt to trace etymologies of slang words—putting "slang" in a book title for the first time.

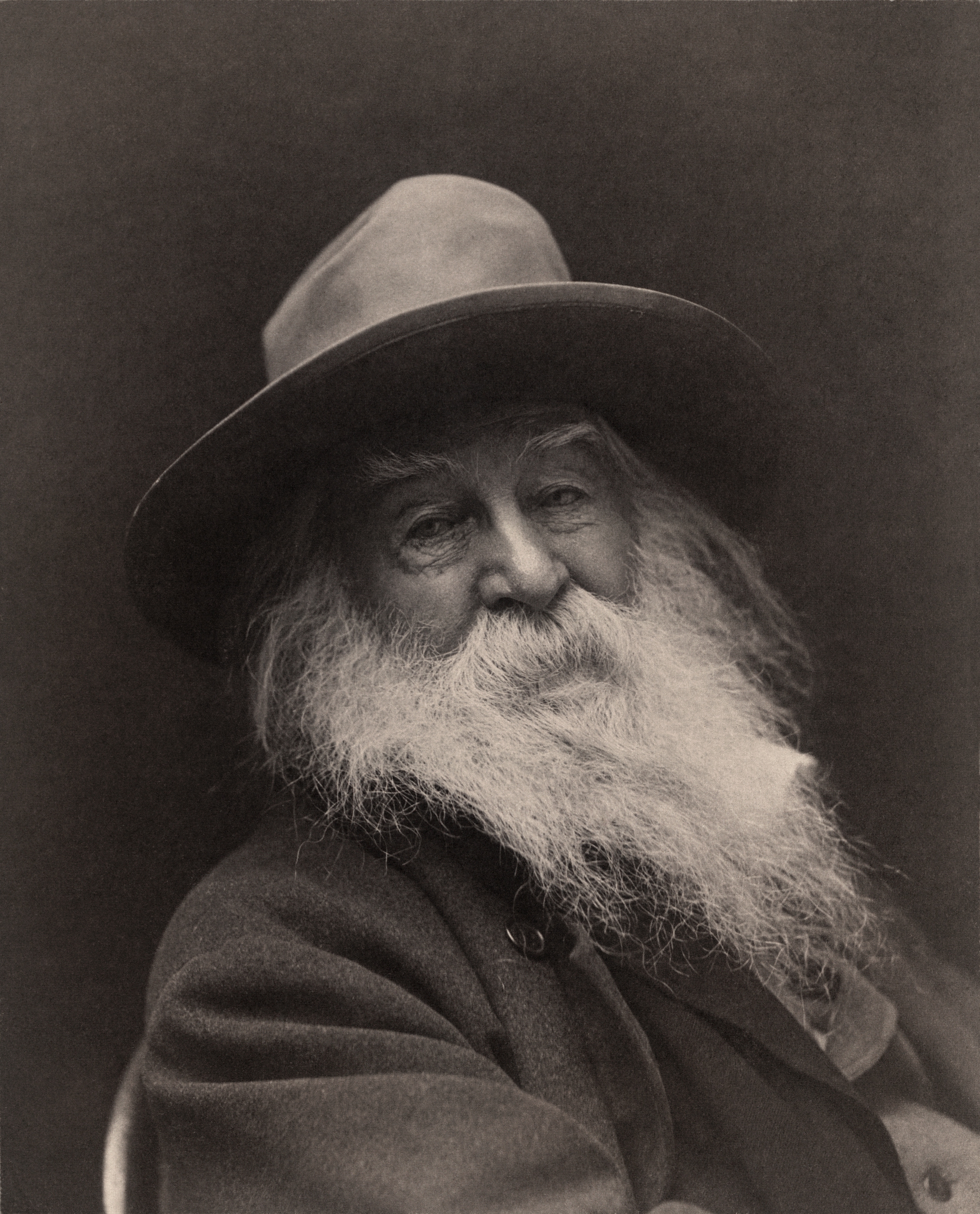

Walt Whitman

Defended slang as democratic expression in "Slang in America" (1885), arguing that living language comes from the people, not from academies.

“Slang... is the lawless germinal element, below all words and sentences, and behind all poetry.”

H.L. Mencken

Published "The American Language" (1919), rehabilitating American English and its slang as legitimate linguistic innovation, not colonial degradation.

“Slang in its origin is nearly always respectable; it is devised not by the stupid populace, but by individuals of wit and ingenuity.”

Eric Partridge

Published "A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English" (1937), the standard reference for decades, treating slang with scholarly rigor and obvious delight.

“Slang is language at play.”

Jonathon Green

Published "Green's Dictionary of Slang" (2010), the largest English slang dictionary ever compiled with 125,000+ headwords spanning 500 years.

“Slang is the poetry of everyday life.”

Gretchen McCulloch

Published "Because Internet" (2019), documenting how digital communication creates new forms of informal language and changes how we write.

“The internet didn't create new types of informal language... it made informal writing normal.”

Slang Today

The Internet as a Slang Engine

In 1999, Urban Dictionary appeared, promising definitions “written by you.” The democratic impulse Mencken championed had found its ultimate expression: anyone could define slang, anyone could vote on meanings.

By the 2020s, TikTok accelerated slang evolution to unprecedented speed. Words like rizz, bussin', and no cap traveled from niche usage to mainstream awareness in weeks rather than decades.

“The internet didn't create new types of informal language... it made informal writing normal.”

— Gretchen McCulloch, Because Internet, 2019

To trace the word slang is to trace the contested boundary between proper speech and everything that threatens it.

From Toldervy's 1756 novel to today's crowdsourced definitions, the word has named the outside, the excluded, the improper—even as that boundary constantly shifts.

The word performs what it describes: uncertain origin, marginal beginnings, gradual legitimization. Like the vocabulary it names, slang arrived from somewhere we cannot quite pin down.

And like language itself, it refuses to hold still.

“Slang is the poetry of everyday life.”

— Jonathon Green

Timeline

Sources

Primary Sources

- Oxford English Dictionary, “slang, n.³” and etymology notes

- Green's Dictionary of Slang, Jonathon Green (2010)

- Online Etymology Dictionary

Historical Dictionaries

- Francis Grose, A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785)

- John Camden Hotten, The Slang Dictionary (1859)

- Eric Partridge, A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (1937)

Scholarly Works

- Julie Coleman, The Life of Slang (2012)

- H.L. Mencken, The American Language (1919)

- Gretchen McCulloch, Because Internet (2019)

- Connie Eble, Slang and Sociability (1996)

- Michael Adams, Slang: The People's Poetry (2009)

Images

- William Hogarth, “Gin Lane” (1751) — Wikimedia Commons

- Francis Grose portrait — Yale Center for British Art

- H.L. Mencken — Library of Congress

- Walt Whitman — Library of Congress

Note on Etymology: This essay presents the current scholarly consensus that the etymology of “slang” remains uncertain. The Scandinavian theory is the leading hypothesis but has not been definitively proven.

The Social Life of Slang

Why It Exists

Every slang word is born for a reason. And every slang word eventually dies. Understanding why reveals what slang actually does.

Secrecy

From thieves' cant to teen texting—keeping outsiders out

Identity

“We speak this way; they don't”—marking belonging

Rebellion

Rejecting “proper” language, asserting autonomy

Freshness

Novelty, economy, expressiveness—saying more with less

The Lifecycle of a Slang Word