Phonē: From Voice to Device

The 2,800-Year Biography of the Word in Your Pocket

Phonē: From Voice to Device

The 2,800-year biography of the word in your pocket

Proto-Indo-European *bhēh₂- — “to speak.” The same root that gave us fame, fate, and fable also gave us phone. This is its story.

The Greek Word

8th c. BCE – 1st c. CEIn the world of ancient Greek, φωνή was not a technical term. It was a living word—used by poets, philosophers, and playwrights to name the human voice, the cry of pain, the sound of instruments, and even language itself. Homer sang it. Aristotle analyzed it. For a thousand years, it simply meant the breath that carries meaning.

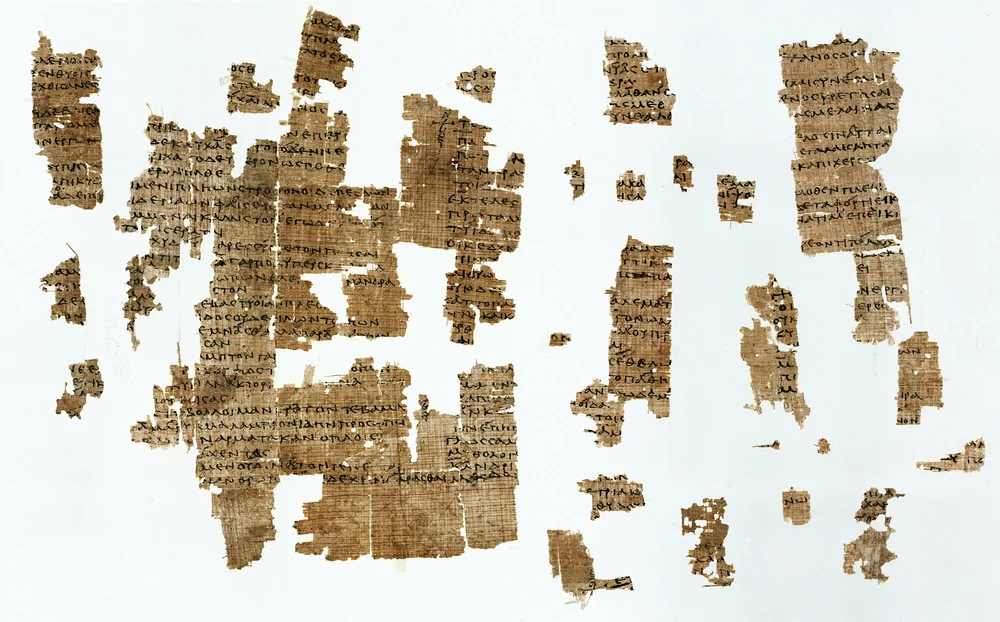

φωνή in Homer

The Iliad and Odyssey contain the earliest literary attestations of φωνή. In Homer, the word names both human voice and divine utterance—the breath of Achilles and the call of Athena alike. It described something at once physical (sound waves in air) and sacred (the vehicle of meaning between minds).

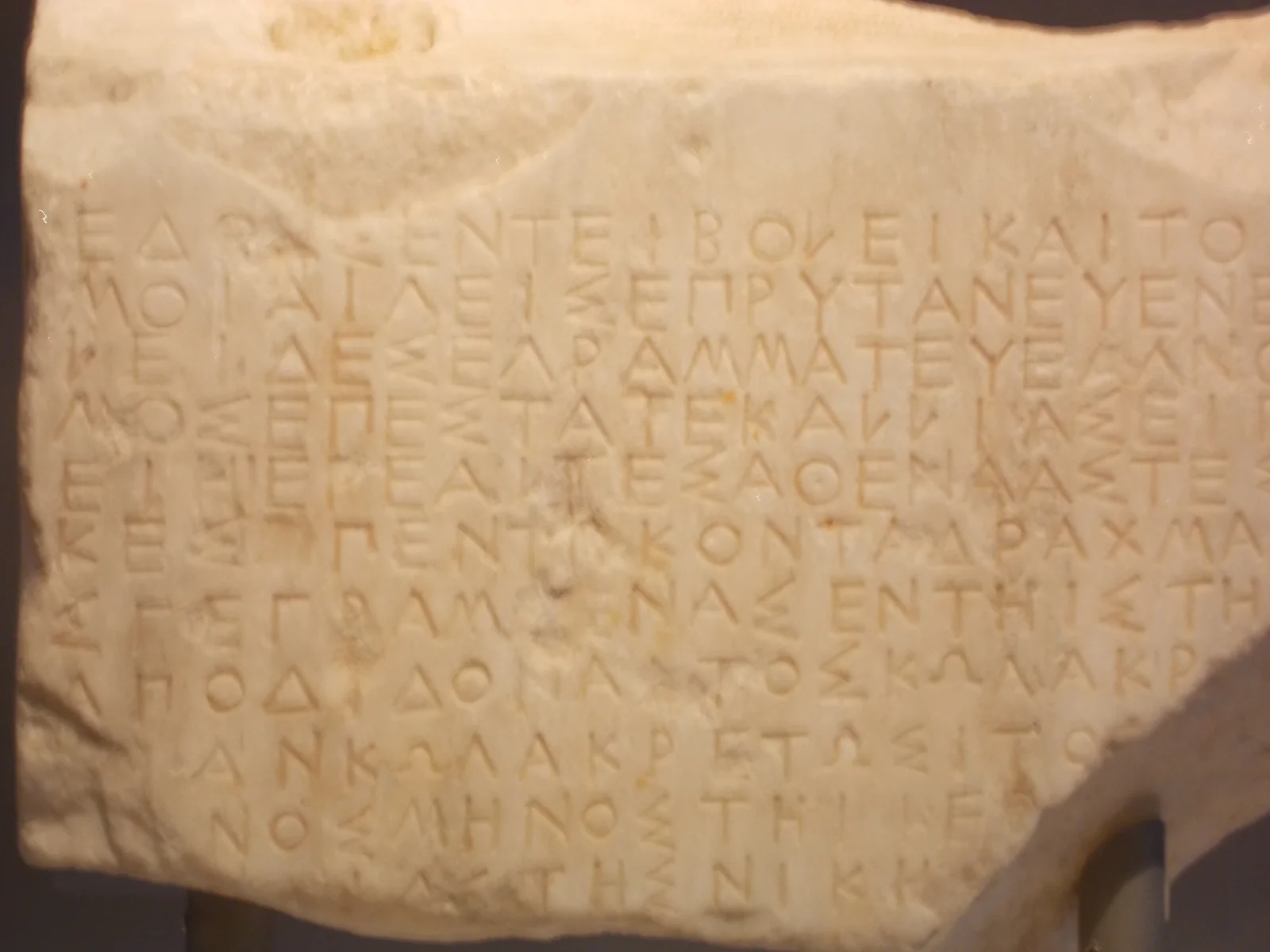

“Spoken words are the symbols of mental experience and written words are the symbols of spoken words.”

— Aristotle, De Interpretatione (4th c. BCE)

“Sound Significant by Convention”

Aristotle transformed φωνή from a common word into a philosophical concept. In De Interpretatione, he defined it as φωνή σημαντική κατὰ συνθήκην—voice that carries meaning by human agreement, not by nature. This was the first philosophy of language: sound becomes meaning only because we collectively agree it does.

“A name is a spoken sound significant by convention... no name is a name naturally but only when it has become a symbol.”

— Aristotle, De Interpretatione, 16a19\u201328

Seven Senses

φωνή was not a single-meaning word. The Liddell-Scott-Jones Greek lexicon records seven distinct senses: voice, sound, cry, language, dialect, pronunciation, and vowel. A word with seven lives—each feeding into its future.

Homer

Earliest literary source for φωνή

~8th c. BCE

The Iliad and Odyssey contain the earliest literary attestations of φωνή, meaning 'voice' and 'sound.'

Aristotle

Philosopher of voice

384–322 BCE

Defined φωνή as 'sound significant by convention' in De Interpretatione — the first philosophy of language.

The Latin Bridge

1st c. BCE – 17th c. CEφωνή does not enter Latin directly. Latin had its own word for voice: vōx. Instead, Greek compounds containing φωνή filter into Latin through scholarship and the Church, then into early modern European languages. The word sleeps for centuries—waiting.

The Sleeping Root

Three ancient Greek compounds survive the journey into English: symphony (1590s), euphony (1623), and cacophony (1656). They arrive quietly, spaced decades apart—together-sound, good-sound, bad-sound. All three carry φωνή inside them, but nobody notices. The root is dormant but alive.

symphony enters English

“together-sound” — from Greek συμφωνία

euphony enters English

“good-sound” — from Greek εὐφωνία

cacophony enters English

“bad-sound” — from Greek κακοφωνία

Why Greek?

The Renaissance and Enlightenment chose Greek for scientific vocabulary. Latin had vōx and sonus, but Greek phonē was more versatile for compounds. Telephone sounds authoritative; fariloquium does not. Greek became the preferred building material for the modern world's new words.

Greek became the LEGO of scientific naming—modular roots that snap together into precise meanings. Tele + phonē. Micro + phonē. The system is so productive that we still use it today.

The Compound Explosion

1827 – 1900In 70 years, Greek φωνή spawns more new English words than it had in the previous 2,500 years combined. The 19th century's appetite for invention—and for naming inventions—turns a quiet Greek root into the most productive combining form in telecommunications.

The First Compounds

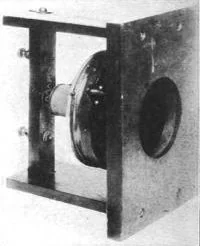

In 1827, Sir Charles Wheatstone coins microphone for an acoustic amplifier. Around 1828, Jean-François Sudré coins téléphone for a failed musical signaling system. The words exist before the inventions they will eventually name.

Morphological Anatomy

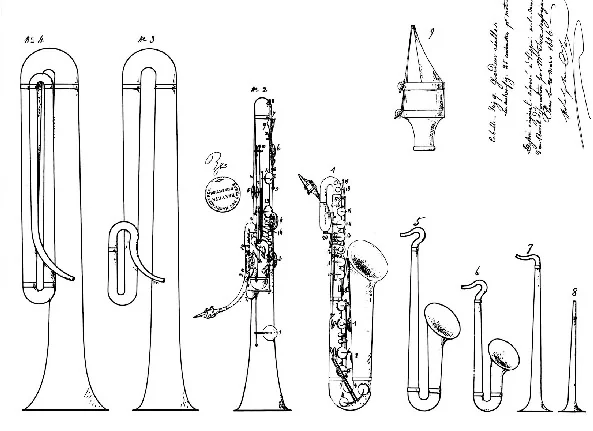

The Sax-Sound

In 1846, Adolphe Sax patents the saxophone. The name: Sax + phonē, “the sound of Sax.” The only major instrument named after a person plus the Greek word for voice. φωνή enters the world of music.

The Family Grows

Xylophone (wood-sound, 1866), megaphone (great-sound, 1878), gramophone (writing-sound, 1887). Each compound is a miniature etymology lesson. A pattern crystallizes: -phone means transmission, -graph means recording.

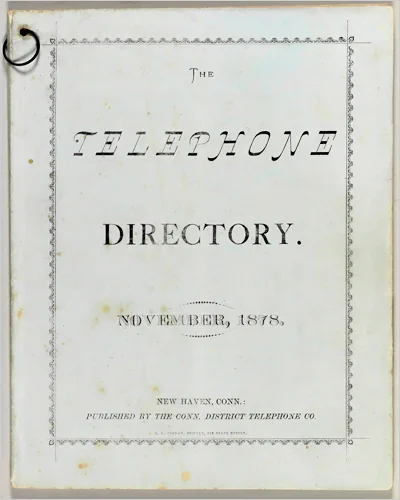

The Telephone Before the Telephone

The word telephone existed for 48 years (1828–1876) before Bell’s device. Sudré’s musical system, Bourseul’s 1854 concept paper, Reis’s 1861 Telephon in Frankfurt. Three inventions, one word—waiting for the right device.

“Speak against one diaphragm and let each vibration make or break the electric current... the other diaphragm will reproduce the transmitted vibrations.”

— Charles Bourseul, L\u2019Illustration, 1854

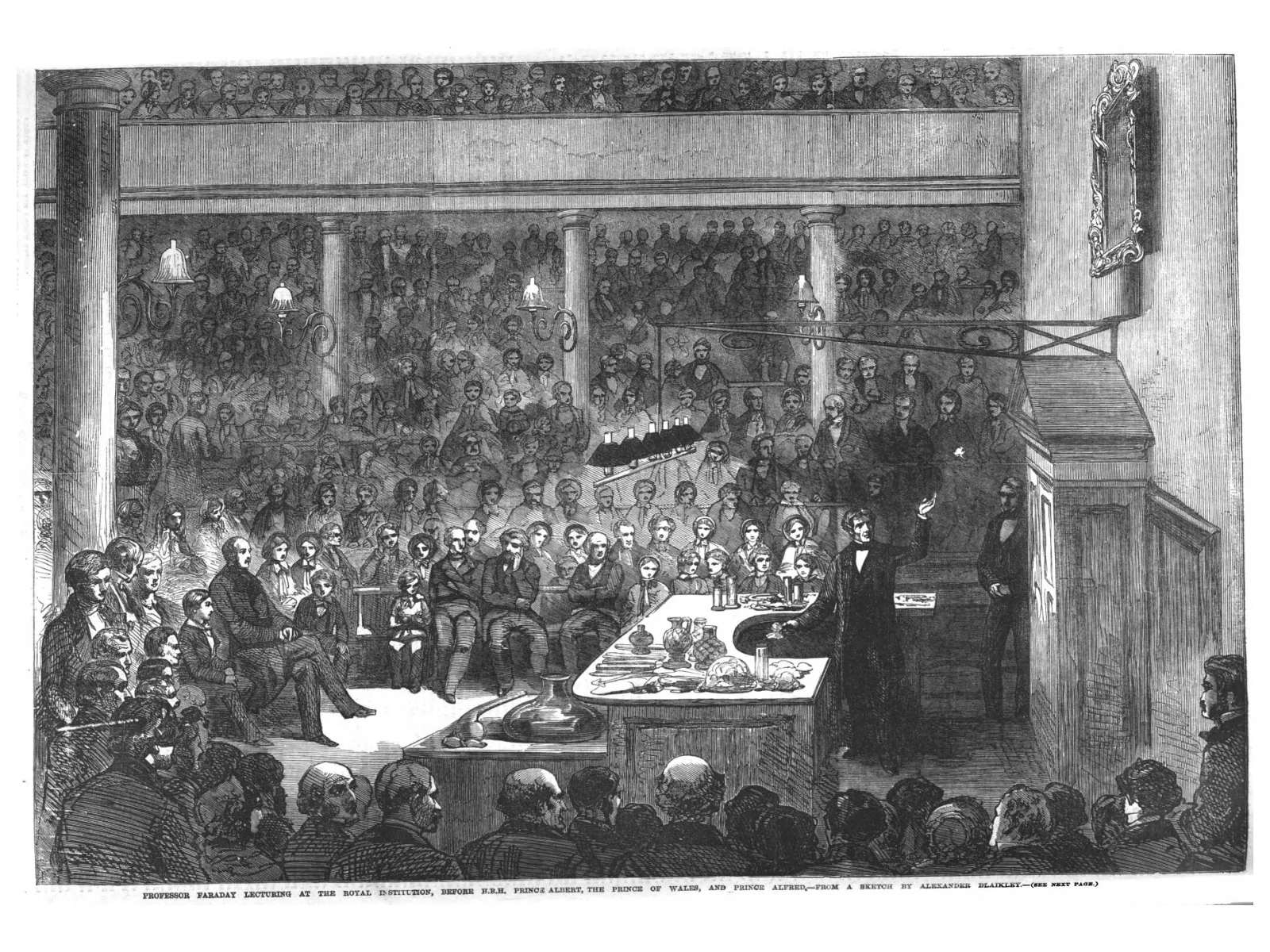

Sir Charles Wheatstone

Coined microphone (1827)

1802–1875

Created 'microphone' (Greek mikros + phonē = 'small-sound') for an acoustic amplification instrument.

Jean-François Sudré

First to use téléphone (~1828)

1787–1862

Coined 'téléphone' for a musical signaling system. The word existed 48 years before Bell’s device.

Adolphe Sax

Namesake of saxophone (1846)

1814–1894

The saxophone = Sax + phonē ('Sax-sound'). The only major instrument named after a person + the Greek word for voice.

Johann Philipp Reis

Coined Telephon (1861)

1834–1874

Built the first electrical sound-transmitting device and named it das Telephon — 15 years before Bell.

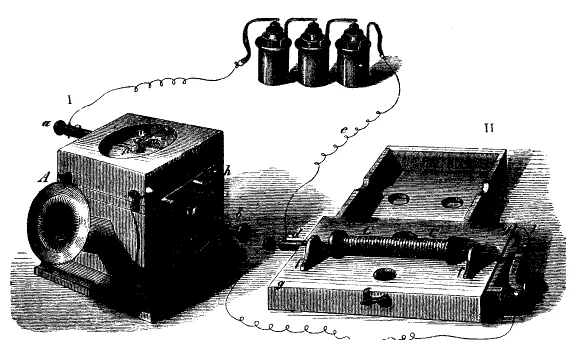

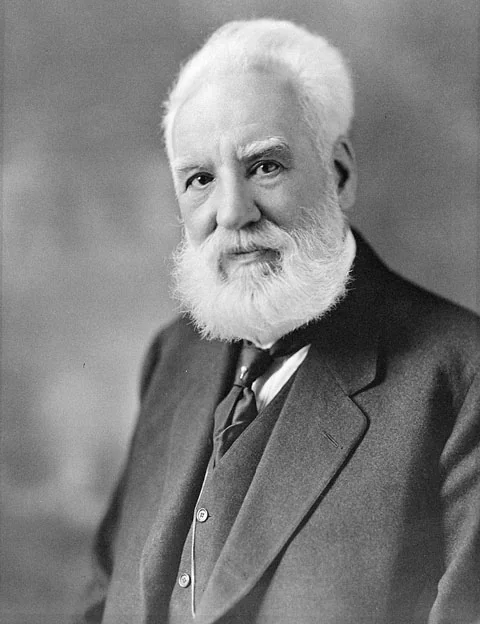

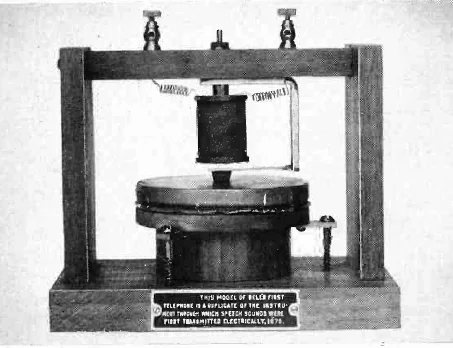

The Bell Moment

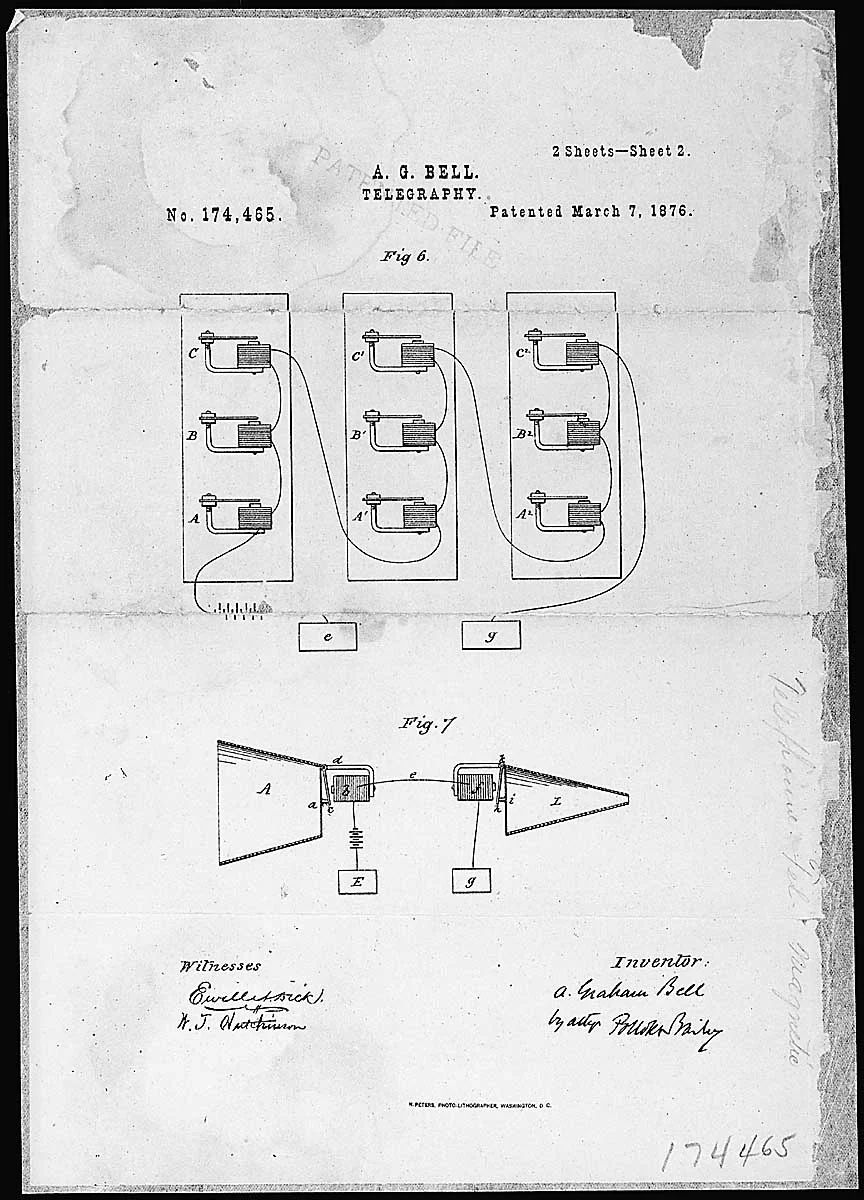

1876February 14, 1876. Alexander Graham Bell files US Patent 174,465. The Greek compound telephone becomes the most famous word of the industrial age. But the deeper story is biographical: Bell's life was about voice before it was about wires.

The Voice Family

Bell's grandfather was an elocution professor. His father, Alexander Melville Bell, invented Visible Speech—a phonetic notation system for the deaf. Alexander Graham Bell himself was a professor of vocal physiology at Boston University. His wife, Mabel, was deaf. The man who gave the world the telephone spent his life studying φωνή.

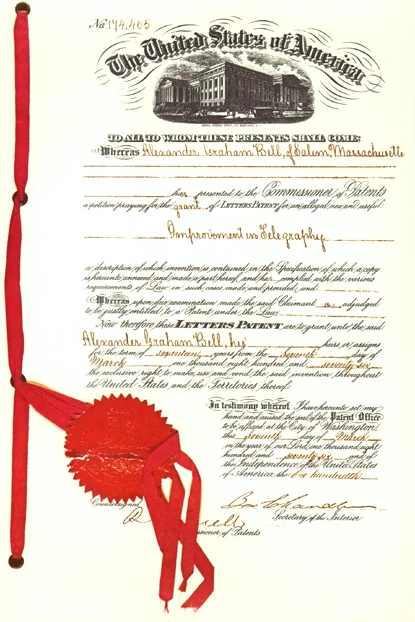

Patent 174,465

February 14, 1876: Bell files US Patent 174,465, titled “Improvement in Telegraphy.” Elisha Gray files a telephone caveat the same day. Bell's application arrives hours earlier. The most consequential few hours in the history of naming.

“Mr. Watson \u2014 come here \u2014 I want to see you.”

— Alexander Graham Bell, first telephone transmission, March 10, 1876

The Word Goes Global

Within a year, telephone enters every European language: French téléphone, German Telefon, Spanish teléfono. But East Asian languages do something different—they calque the concept: Japanese 電話 (denwa, “electric speech”), Mandarin 电话 (diànhuà, “electric speech”). Arabic coins هاتف (hātif, “caller”). Finnish invents puhelin (“speaking-instrument”).

Alexander Graham Bell

Made telephone globally famous

1847–1922

Filed US Patent 174,465 on February 14, 1876. A professor of vocal physiology whose lifework was the human voice.

Elisha Gray

Patent rival (same-day filing)

1835–1901

Filed a telephone caveat the same day as Bell. Lost the patent race by hours.

Thomas Edison

Coined phonograph (1877)

1847–1931

Created the phonograph ('sound-writer') and popularized megaphone ('great-sound'). Established the -phone vs. -graph distinction.

The Great Truncation

1878 – 1995The most dramatic clipping in English. Within two years of Bell's patent, telephone loses its first four letters. Within fifty years, phone is standard. Within a century, it is generating its own compounds. The child has overtaken the parent.

Two Years

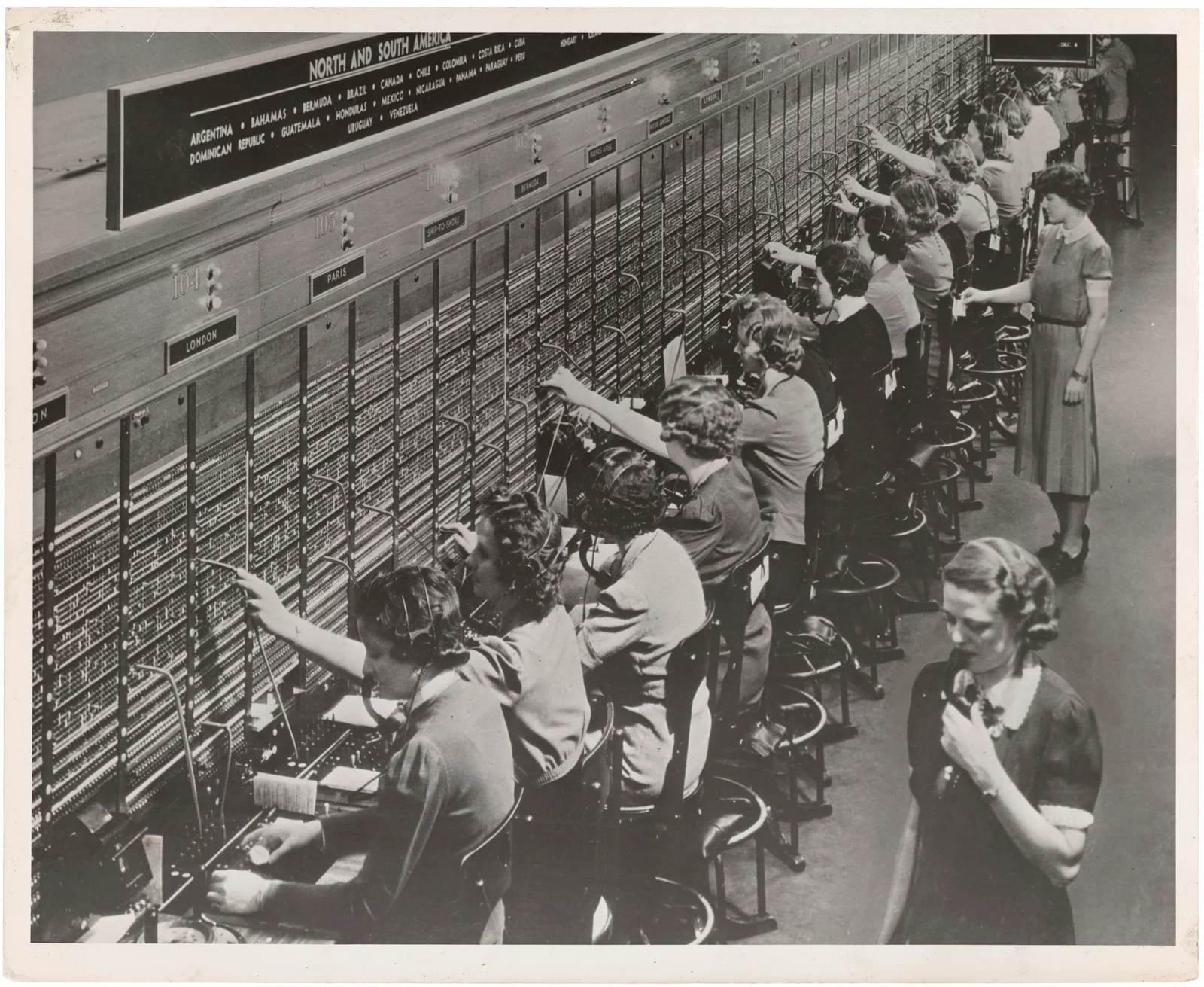

1878: The Des Moines Register uses phone—the first attestation. The clipping happened at the speed of adoption. When a word becomes so common that it sheds its prefix, linguists call it clipping. Telephone to phone is one of the fastest major clippings in English history.

The Apostrophe That Vanished

In formal writing, the clipped form was initially written as 'phone—the apostrophe marking the missing tele-. By the 1920s, the apostrophe was gone. Phone was no longer an abbreviation. It was a word.

“Phone: A colloquial shortening of telephone; generally applied to the receiver, but sometimes to the whole apparatus.”

— Century Dictionary, 1895

Phone Builds Its Own Family

Once phone started generating compounds—phone bill (1901), phone booth (1906), phone book (1920)—it was no longer a shortened telephone. It was an independent word. Linguistically, a clipping achieves independence when it produces its own offspring.

When a clipped form starts making its own compounds, the parent word is no longer needed. Phone didn't just shorten telephone—it replaced it.

The Smartphone Singularity

1995 – PresentA word that meant “voice” in ancient Greek now names a device whose primary functions are visual. The phone has outlived its name. This is semantic fossilization—and it tells us something profound about how language works.

smart + phone

1995: “smart phone” appears in print. 1997: Ericsson coins smartphone as one word. 2007: iPhone. The word phone now names a pocket computer. Voice calling is one function among dozens.

The Voice That Isn't

In 2025, a typical smartphone user makes voice calls for less than 15 minutes per day. The device named after the Greek word for “voice” is primarily a camera, messenger, browser, map, wallet, and library. We call it a phone—but it isn't one.

φωνή meant voice. Phone means everything.

Semantic Fossilization

Like pen (from Latin penna, “feather”) and dial (from Latin diālis, “sundial”), phone carries the fossil of an obsolete technology inside its name. The word preserves a meaning the object has abandoned. This is how language works: names outlive their origins. Every word is an archaeology.

The next time you pick up your phone, you are picking up a word that is 2,800 years old. It meant voice. It meant sound. It meant the breath that carries meaning from one mind to another.

The device has changed. The word remembers.

Sources & Further Reading

Primary & Linguistic

- Beekes, Robert. Etymological Dictionary of Greek (2 vols.), Leiden: Brill, 2010

- Liddell, Scott & Jones. A Greek-English Lexicon (9th ed.), Oxford, 1940

- Oxford English Dictionary, entries for “phone,” “telephone,” and derivatives

- Chantraine, Pierre. Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grecque, Paris: Klincksieck, 1968–80

- Aristotle. De Interpretatione (trans. J.L. Ackrill), Clarendon, 1963

Historical & Biographical

- US Patent 174,465 — Bell, “Improvement in Telegraphy,” Feb 14, 1876

- Casson, Herbert N. The History of the Telephone, A.C. McClurg, 1910

- Everson, George. The Telephone Patent Conspiracy of 1876, McFarland, 2000

- Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language (2nd ed.), 2003

- Horrocks, Geoffrey. Greek: A History of the Language and its Speakers (2nd ed.), Wiley-Blackwell, 2010

Word Formation & Morphology

- Marchand, Hans. The Categories and Types of Present-Day English Word-Formation, C.H. Beck, 1969

- Algeo, John. Fifty Years Among the New Words, Cambridge, 1991

- Harper, Douglas. Online Etymology Dictionary (etymonline.com)

- Bourseul, Charles. “Transmission électrique de la parole,” L’Illustration, Aug 26, 1854