The Weightof a Word

A History of the N-Word in America

How a Latin color term became infrastructure for dehumanization — and how people fought back

Every word has a journey.

This one began in ancient Rome.

The most offensive word in the English language.

This is the story of how that happened.

When Words Become Weapons

What makes a word wound?

This is not a story of etymology alone. It is a study of how language becomes infrastructure — how words are laid like bricks to build systems of power, exclusion, and dehumanization.

The word at the center of this essay traveled from Latin classrooms to slave ships, from legal codes to minstrel stages, from Supreme Court decisions to hip-hop lyrics. At every stage, it was contested.

This is not merely a story of harm. It is a story of harm met by courage. At every moment when the word was weaponized, someone fought back.

“Language doesn't just describe the world. It builds it.

The Neutral Root

The word begins in Latin: niger. It meant black — the color. The dark ocean. Black cloth. Nothing more.

The Oxford English Dictionary traces the etymology through Romance languages: Spanish and Portuguese negro, French nègre. Each carried the word across the Atlantic, and each carried people in chains.

The word's meaning changed not in dictionaries but in ships, markets, and laws. When European powers began the transatlantic slave trade, the color descriptor became a category — and the category became a cage.

By the time English adopted the term in the 1570s, it was already entangled with commerce in human beings. The neutral root had taken on weight that would never be removed.

First English Traces

The Oxford English Dictionary finds the first written English use in 1574: "Negar." Other early spellings include "niger," "neger," and "nigar." They appear in travel writings, commercial documents, and colonial records.

By the 17th century, spellings had stabilized toward the form we recognize. The question of whether there was ever a "neutral" period in English usage remains debated — the earliest attestations already occur in contexts of trade, colonization, and hierarchy.

Samuel Johnson's 1755 Dictionary of the English Language has no separate entry for the slur — only "Negro." The variant was considered dialectal, vulgar, used in commercial speech and by the lower classes. But it was everywhere.

Language of the Trade

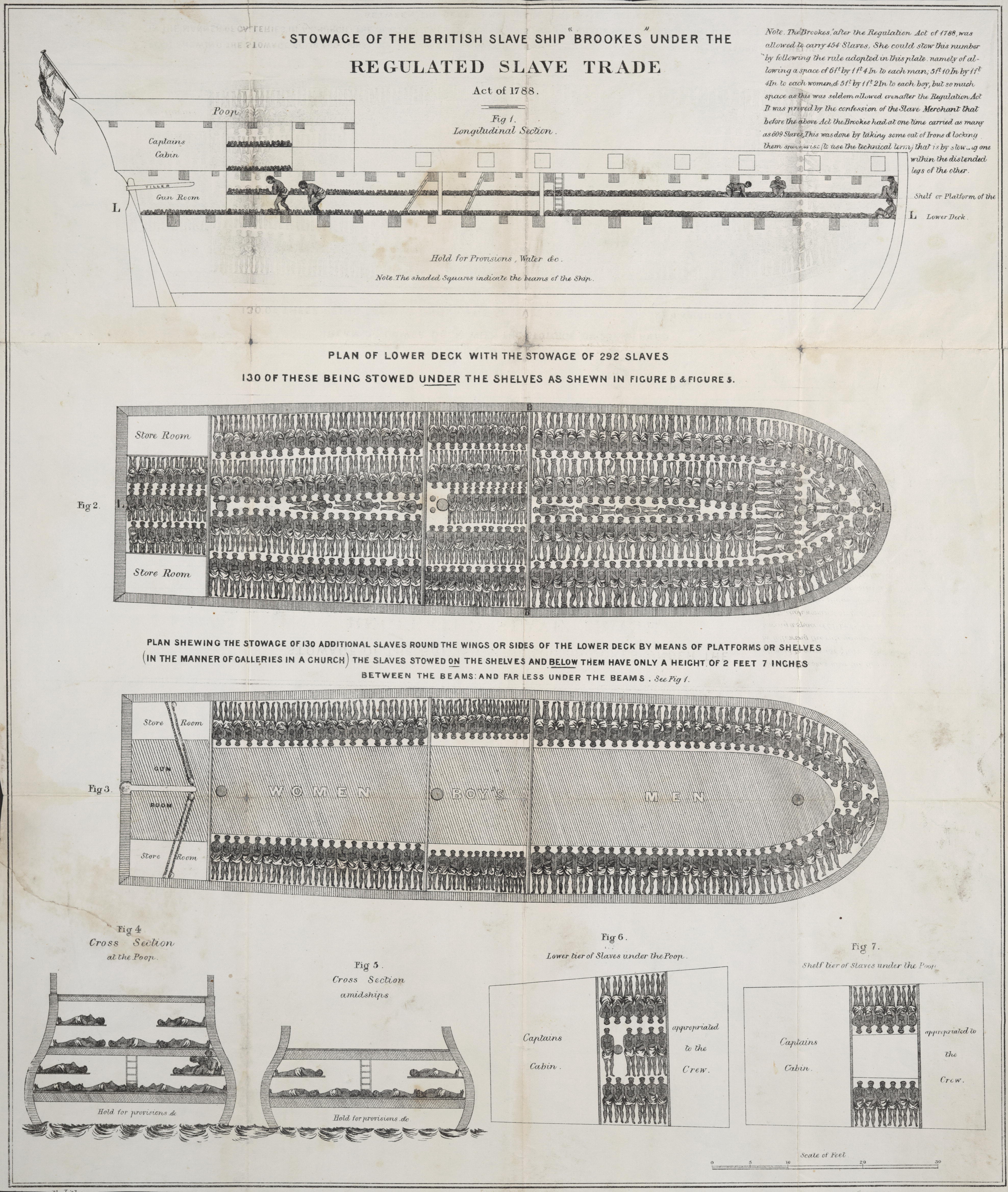

The slave ship Brookes diagram became an icon of abolitionist campaigns.

Diagram of the slave ship Brookes, 1788. Library of Congress.

Public Domain

The Atlantic slave trade moved not only human beings but language. The word traveled the same routes as the enslaved — from African coasts through the Middle Passage to American ports.

In colonial law, the word became administrative vocabulary. Virginia's 1705 slave codes, the South Carolina Negro Act of 1740, and countless other legal documents used racial terminology to define who could be owned, who could testify, who counted as human.

The infamous diagram of the slave ship Brookes, published in 1788, became an icon of abolitionist campaigns. The word that described the people packed into that hold was becoming what it would remain: a tool for categorizing human beings as property.

Slavery as System

By the 19th century, the word was fully weaponized — embedded in law, commerce, and everyday speech. The Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision of 1857 declared that Black Americans "had no rights which the white man was bound to respect."

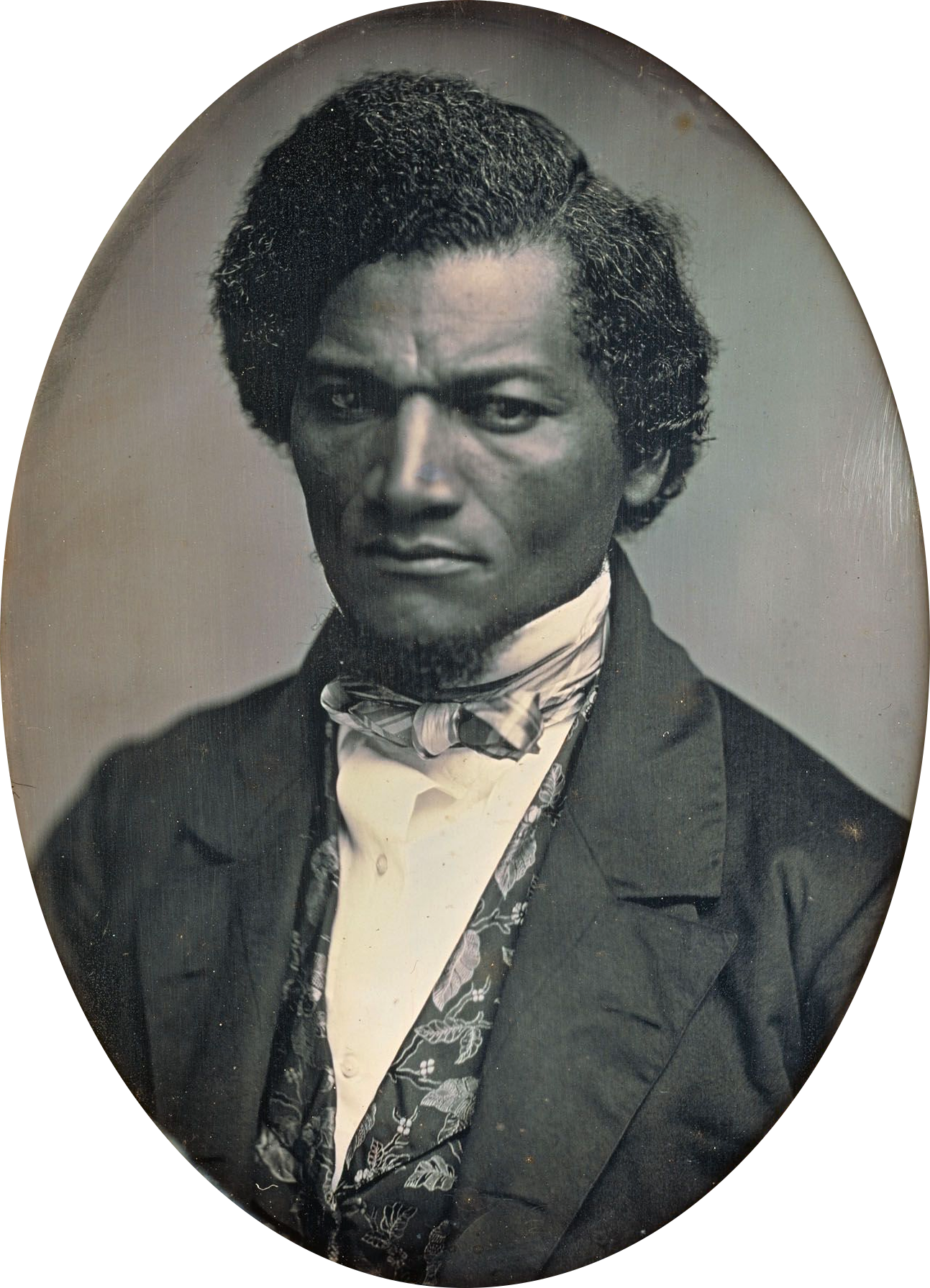

But resistance was constant. Frederick Douglass, escaped from slavery, became the most photographed American of the 19th century. He used his image deliberately — to counter the caricatures, to insist on his humanity, to speak truths that shook the nation.

Abolitionists published newspapers, gave speeches, and built movements that challenged not just slavery but the language that made it possible. The word could wound — but it could also be confronted.

Frederick Douglass by Samuel J. Miller, c. 1847-52. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Frederick Douglass

1818–1895The Great Orator

Escaped slavery to become the foremost African American voice of the 19th century. Used oratory, journalism, and autobiography to challenge every premise of white supremacy.

“What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?”

— Rochester, 1852

Minstrelsy's Normalization

In the 1830s, Thomas "Daddy" Rice created the "Jim Crow" character, launching blackface minstrelsy as America's dominant entertainment form. By mid-century, minstrel shows played to packed houses across the nation.

The damage was not just in the performances but in the normalization. Generation after generation learned to laugh at racist language and imagery. The word — along with an entire vocabulary of caricature — became entertainment vocabulary.

The name "Jim Crow" would later name an entire system of segregation. Entertainment vocabulary became legal category. The line between the stage and the courthouse was never as clear as people pretended.

Reconstruction's Betrayal

During Reconstruction, Black Americans served in Congress and built schools.

First Colored Senator and Representatives, Currier & Ives, 1872. Library of Congress.

Public Domain

The end of the Civil War brought constitutional revolution. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery. The 14th established citizenship. The 15th guaranteed voting rights. For a moment, everything seemed possible.

Black Americans served in Congress, built schools, created communities. But the counterrevolution came swiftly. Southern states passed Black Codes. Violence terrorized Black voters. In 1877, federal troops withdrew as part of a political compromise.

The door that had briefly opened slammed shut. The word persisted — in law, in violence, in everyday humiliation. The brief hope of Reconstruction gave way to something worse.

Jim Crow's Reign

Signs marking "White" and "Colored" made racial hierarchy visible on the landscape.

Colored Waiting Room sign, 1943. Library of Congress.

Public Domain

For nearly 80 years, Jim Crow laws enforced separation in every sphere of American life. Signs marking "White" and "Colored" made racial hierarchy visible on the landscape. The Supreme Court's Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) declared segregation constitutional.

The violence was not only legal. Lynching terrorized Black communities. Ida B. Wells documented over 700 murders, exposing the lies used to justify racial terror. W.E.B. Du Bois analyzed "the problem of the color-line."

But resistance never stopped. The NAACP organized. A generation prepared for what would come. The word appeared on signs, in courtrooms, in the mouths of mobs — and in the speeches of those who refused to accept it.

Ida B. Wells, photograph by Mary Garrity, c. 1893. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Ida B. Wells

1862–1931Anti-Lynching Crusader

Documented over 700 lynchings, exposing how racial terror was justified through racist language and mythology.

“The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.”

— A Red Record, 1895

W.E.B. Du Bois, photograph by C.M. Battey, c. 1918. Library of Congress.

W.E.B. Du Bois

1868–1963Scholar and Civil Rights Pioneer

First African American to earn Harvard Ph.D. Co-founded NAACP. Analyzed racism with scholarly precision and moral urgency.

“The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.”

— The Souls of Black Folk, 1903

The Dictionary Learns

For centuries, dictionaries avoided or minimized the word. The OED's first edition (1889) noted "usually contemptuous." By the 1960s, dictionaries added explicit warnings. Today's entries call it "one of the most offensive words in English."

The dictionary's evolution mirrors society's. From absence to euphemism. From neutral documentation to explicit condemnation. The very existence of entries for "the N-word" shows how language evolves to handle what it cannot escape.

Webster's 1934: "vulgar." 1961: "usually offensive." 2023: "perhaps the most offensive word in English." The labels intensified as the culture changed. The dictionary learned what the wounded had always known.

Contesting Language

The Civil Rights Movement was, in part, a battle over language — who could speak, whose words mattered, what vocabulary would define America.

Martin Luther King Jr. offered counter-language: "content of character," "beloved community," "the fierce urgency of now." James Baldwin analyzed how racist language functioned as psychological weapon — and how to resist its internalization.

Thurgood Marshall dismantled legal segregation, challenging the language of "separate but equal." The word didn't disappear. But it could no longer go unchallenged.

James Baldwin, photograph by Allan Warren, 1969. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

James Baldwin

1924–1987The Witness

Analyzed how racist language wounds — and how to resist internalization. Made the essay a form of moral witness.

“You can only be destroyed by believing that you really are what the white world calls a nigger.”

— The Fire Next Time, 1963

Thurgood Marshall, Supreme Court of the United States. Public Domain.

Thurgood Marshall

1908–1993The Great Dissenter

Argued Brown v. Board (1954). First African American Supreme Court Justice. Dismantled legal segregation case by case.

“In recognizing the humanity of our fellow beings, we pay ourselves the highest tribute.”

— Supreme Court opinion

The Euphemism Era

By the 1980s, public norms had shifted. The word could no longer be casually spoken in mainstream media. "The N-word" emerged as official euphemism — a word referring to another word, acknowledging what could not be directly said.

Dictionaries added entries for "the N-word." Broadcasting standards evolved. The euphemism became lexicalized — proof that language evolves to handle even its most charged content.

In 2015, President Obama used the full word in a podcast interview, sparking national conversation about when, whether, and how the term could be uttered. The debate continues.

Reappropriation Debates

Within African American communities, some have reclaimed variants of the term — particularly "nigga" — as expressions of solidarity, affection, or defiance. This reappropriation is contested.

Richard Pryor used the word extensively in 1970s comedy — then publicly renounced it after visiting Africa. N.W.A. made reclamation a defining feature of gangsta rap. Hip-hop continues to use the term prolifically.

Scholars distinguish between inter-group use (the slur from outsiders) and intra-group use (complex, variable meanings within community). The question is not settled — and this essay does not settle it.

“The debate continues.

The Open Wound

The word persists — in private racism, online spaces, and occasional public eruptions. Debates continue over teaching texts that contain it, over broadcasting standards, over social media policies, over who can say it and when.

Randall Kennedy's 2002 book brought scholarly analysis to mainstream attention. The NAACP held a symbolic "funeral" for the word in 2007. Neither ended the debate.

Today's questions remain live: How do we teach history that includes this language? How do we quote it when necessary? How do we name what wounds without amplifying the wound?

“How do we name what wounds without amplifying the wound?

Naming What Wounds

This essay began with a question: What makes a word wound?

The answer is not etymology. The Latin root was innocent. The word became a weapon through history — through ships, markets, laws, theaters, and mobs. And at every stage, people fought back.

The word's history is not over. It continues in every choice about language, about teaching, about quotation, about justice. Understanding where it came from is not the same as knowing what to do next. But understanding is where doing begins.

“The weighing continues.

Understanding is where doing begins.

The weighing continues.

Sources & Further Reading

- Oxford English Dictionary — "nigger, n. and adj."

- Randall Kennedy, Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word (2002)

- Jabari Asim, The N Word: Who Can Say It, Who Shouldn't, and Why (2007)

- W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

- James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (1963)

- Ida B. Wells, A Red Record (1895)

- Geneva Smitherman, Word from the Mother: Language and African Americans (2006)

- Library of Congress — African American History Collections

- National Archives — Civil Rights Records

- Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857)

- Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

- Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

This narrative was researched using peer-reviewed scholarship, archival sources, and authoritative historical records. All quotes are verified with primary sources. Images are sourced from public domain archives including the Library of Congress, National Archives, and National Portrait Gallery.